Beachgoers in Brittany, France, discovered something extraordinary and quite unusual. A boulder revealed by low tide had 20 lines of engravings in multiple languages.

Historians struggled to decipher it until 2019 when they turned the riddle into a competition. Learn the secrets behind the mystifying Plougastel-Daoulas boulder.

A Mystery In The Small Town Of Plougastel-Daoulas

In northwestern France, on the coast of Brittany, there is a small town called Plougastel-Daoulas. The town only has 13,000 residents and is famous for its strawberries. But it also contains a lot of history, with churches dating back to the 15th century.

Plougastel-Daoulas also contains some significant harbors, with abandoned forts that were likely used during the French Revolution and both World Wars. Here, residents discovered a mystery that has yet to be fully solved.

ADVERTISEMENT

When The Tide Lowered, The Mystery Was Revealed

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

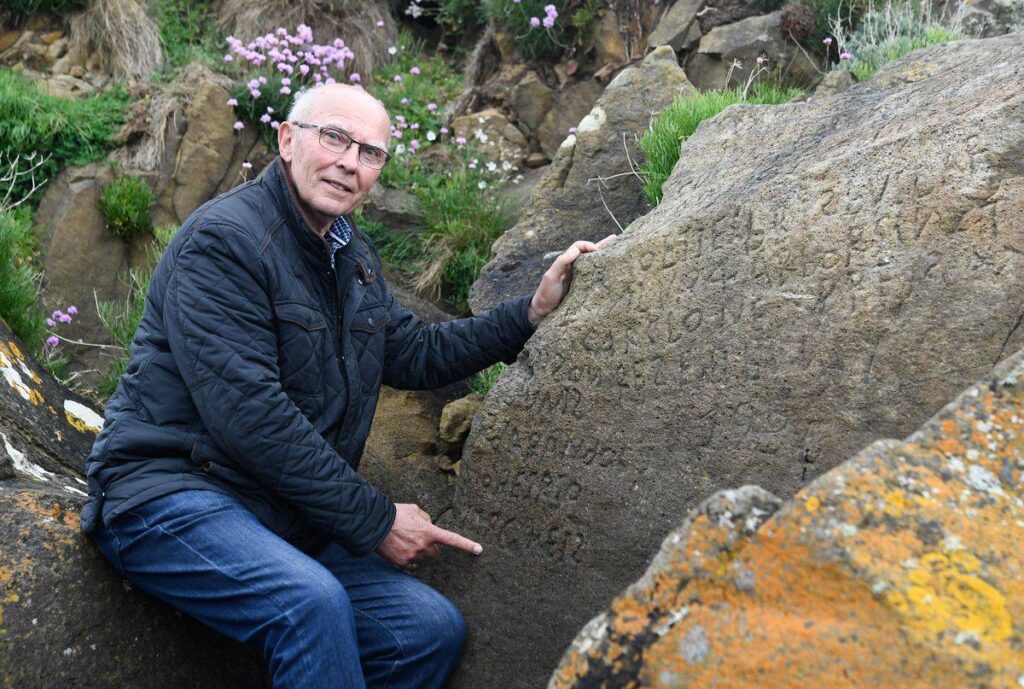

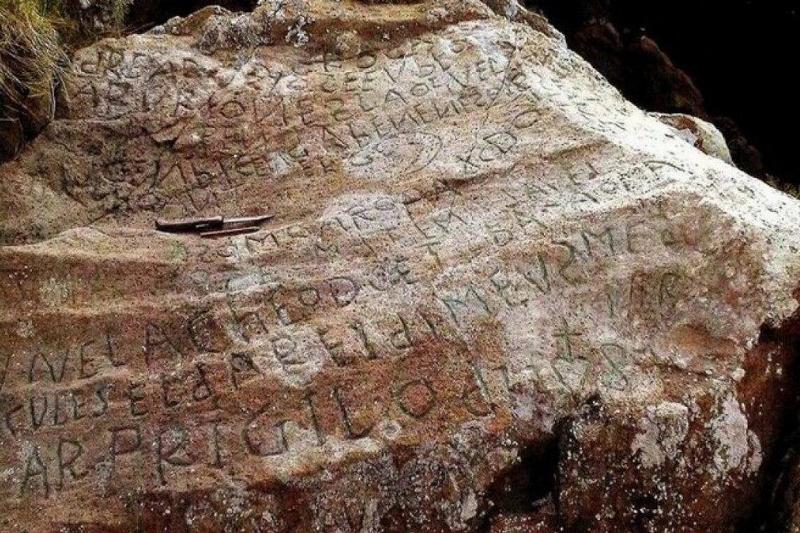

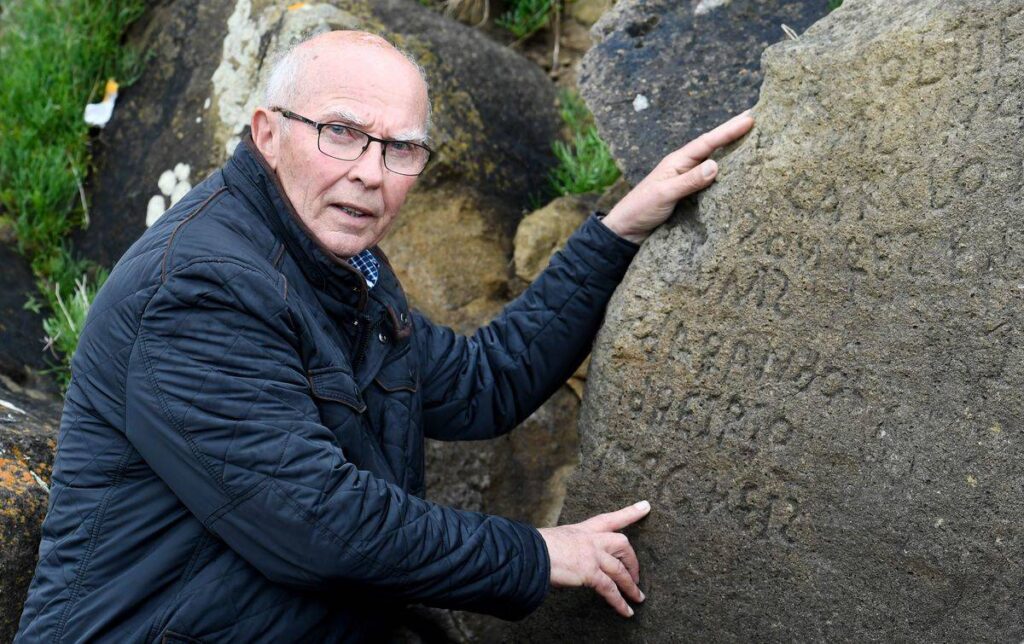

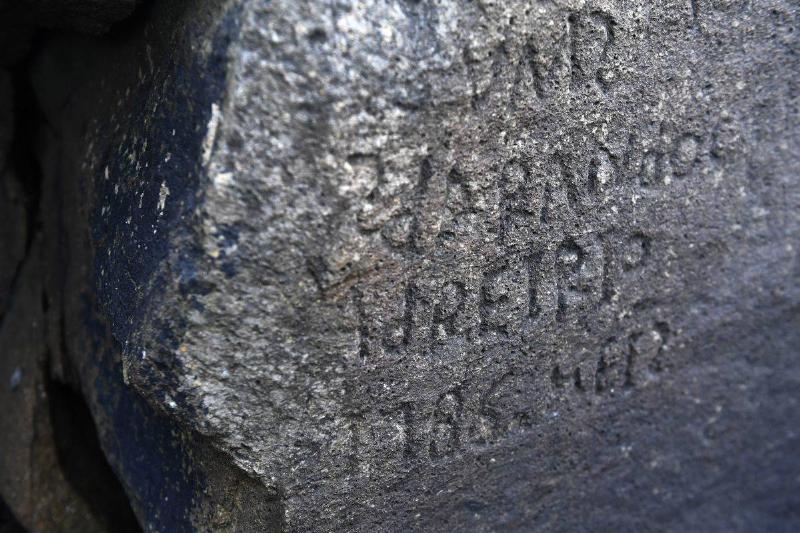

According to The Daily Mail, Plougastel-Daoulas’s mystery was discovered around 2014. When the tide lowered, residents walked along the beach and found a large slab of granite. This three-foot-high rock sat at the base of a peninsula, and it likely appeared because of erosion.

ADVERTISEMENT

Soon, the beachgoers noticed mysterious inscriptions on the boulder. Since they did not know what the engravings said, they reported it to the city. Historians quickly went to work deciphering the rock.

ADVERTISEMENT

What Did It Say?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

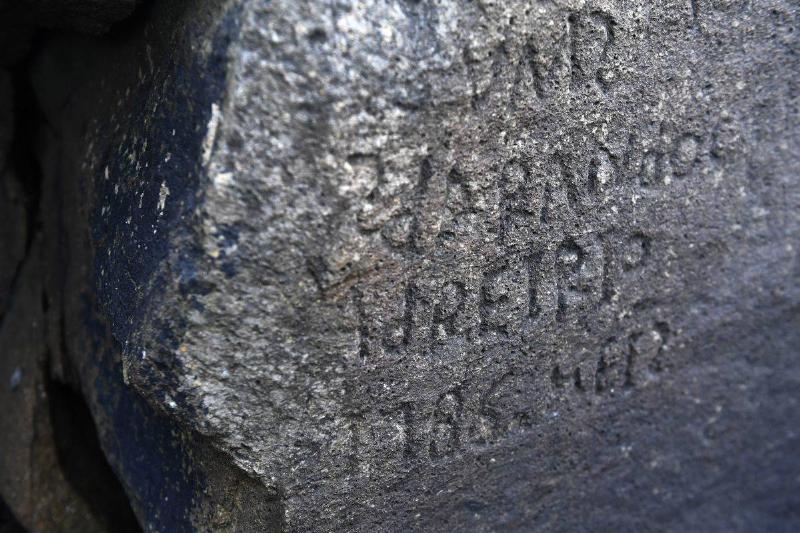

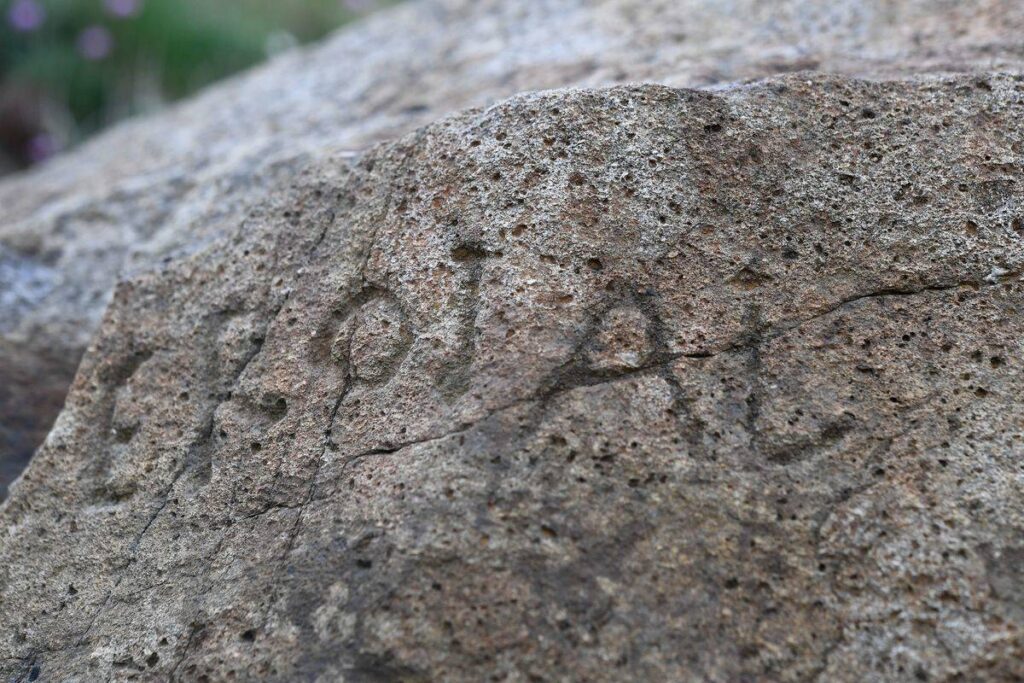

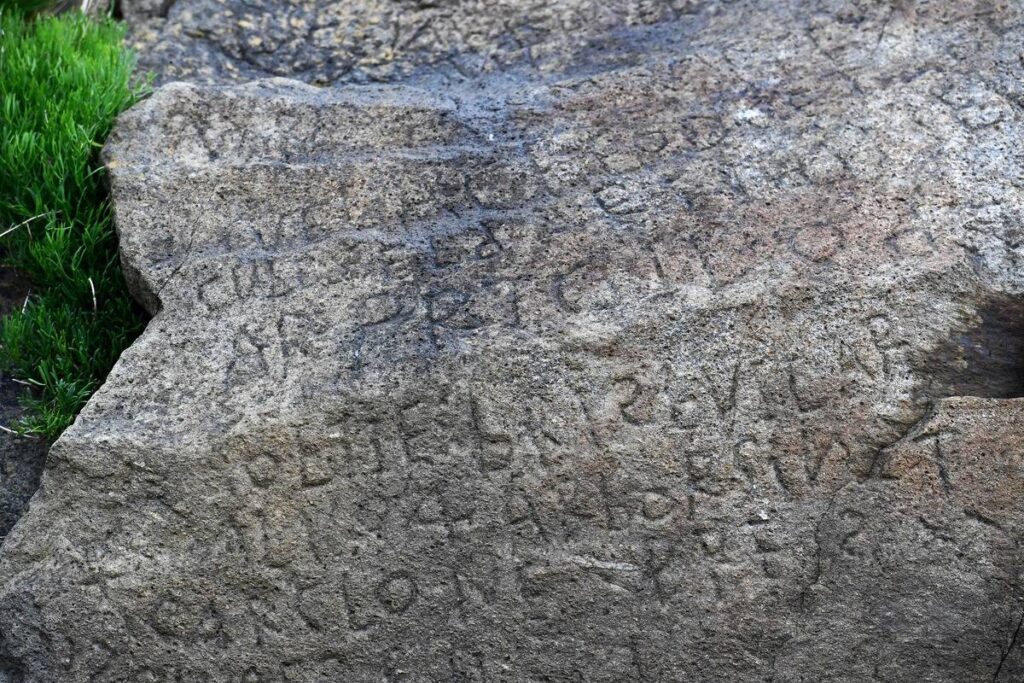

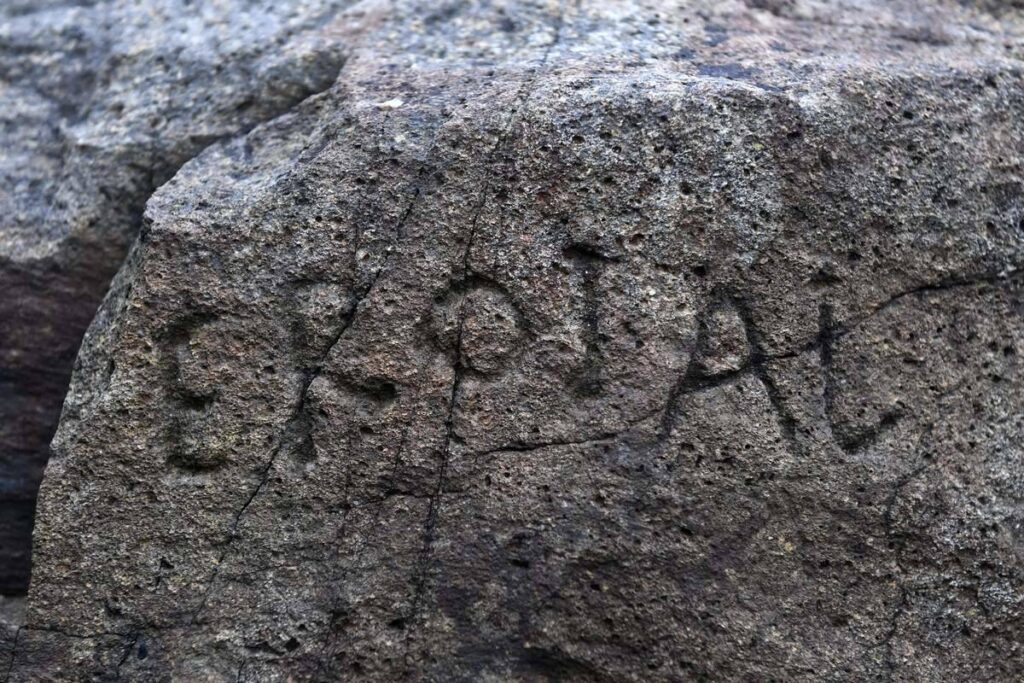

When experts visited the rock, they removed the lichen that had built up from the water. Then, they used chalk to make the engravings more visible. The words roughly translate to, “ROC AR B … DRE AR GRIO SE EVELOH AR VIRIONES BAOAVEL” and “OBBIIE: BRISBVILAR … FROIK … AL.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Because of erosion, many words are missing. The rock also featured two images, one of a sailboat and one of a sacred heart with a cross. It also had two dates, 1786 and 1787.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Words Were In Several Different Languages

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

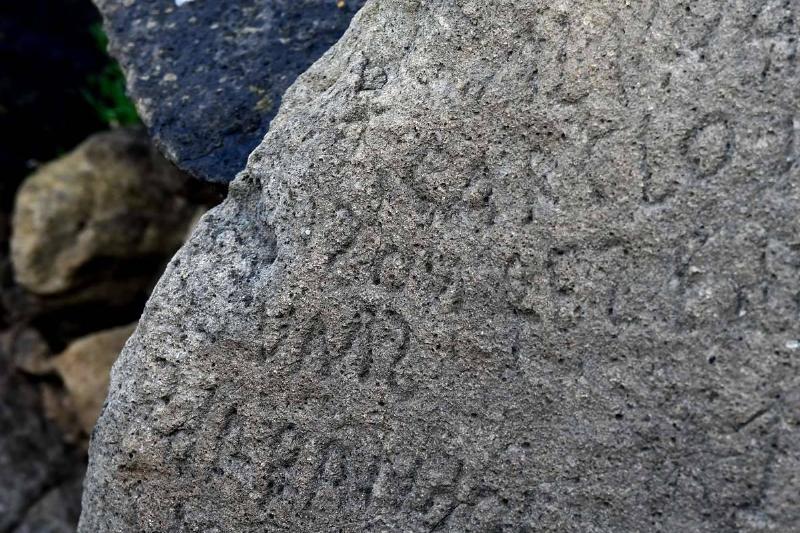

Along with 20 lines of text, the boulder also included several languages. Part of it is Breton, a Celtic language that travelers brought from Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Because of the French government’s efforts to suppress the language, only 200,000 people speak it today.

ADVERTISEMENT

Breton is notoriously difficult to translate since there were not standard spellings in the 18th century. The other language is believed to be Welsh, but because of the erosion, it is difficult to tell.

ADVERTISEMENT

Some Of The Letters Are…Strange, To Say The Least

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Breton specialist François-Pol Castel was one of the first to examine the engraving. He confirmed that most of the words were Breton, some of which were “nest,” “clay,” and “forever.” However, other letters were either out-of-place or written incorrectly.

ADVERTISEMENT

For instance, some French letters were written upside-down or backward. In a few words, the Scandinavian letter Ø appears. This does not belong to the French or Breton alphabets, and historians are stumped as to why it was included.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Engraving’s Ominous First Line

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

When Castel analyzed the engraving, he could only translate the top line. According to him, it reads, “Through these words you will see the truth.” “So it is very mysterious, isn’t it?” he said during an interview.

ADVERTISEMENT

Castel identified at least 20 words that were Breton. However, these were less than half the words in the engraving, and they are not related at all. Castel suggested that the words were spelled phonetically, as Breton was mainly a spoken language, not a written one.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Boulder’s Location Is Significant, Too

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The boulder’s location is as significant as the engraving. It was on the shore of Brest harbor, which saw many soldiers and sailors throughout history. Historians have discovered centuries-old shipwrecks in the water there.

ADVERTISEMENT

A few military forts also stand in the harbor. An ancient army base called Fort du Corbeau, or Crow’s Fort, sits 1/4 miles away from the rock. Many people walked along this beach throughout the centuries, especially during times of war.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dating Back To A Period Of Turmoil

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The engraving is 250 years old, likely dating back to 1786 and 1787, the same dates inscribed on the rock. This was a period of turmoil in the country. After accruing debt in the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution, France was in a financial crisis.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1787 specifically, France entered a two-year-long war with Britain. This conflict launched the crisis that later contributed to the French Revolution. Perhaps these conflicts relate to the mysterious engravings.

ADVERTISEMENT

What Do The Images Tell Us?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Although the words were not translated, historians were able to translate the images. The most notable image was the heart with the sacred cross on top. At the time, this was the symbol of the Chouans. This royalist Catholic group fought against revolutionary forces throughout Brittany.

ADVERTISEMENT

The inscription of the ship is more obvious. The engraver might have been a sailor or member of the Navy. Because France fought with England during this period, it could also represent a ship that sank.

ADVERTISEMENT

It Likely Took Several Days And Several Authors

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

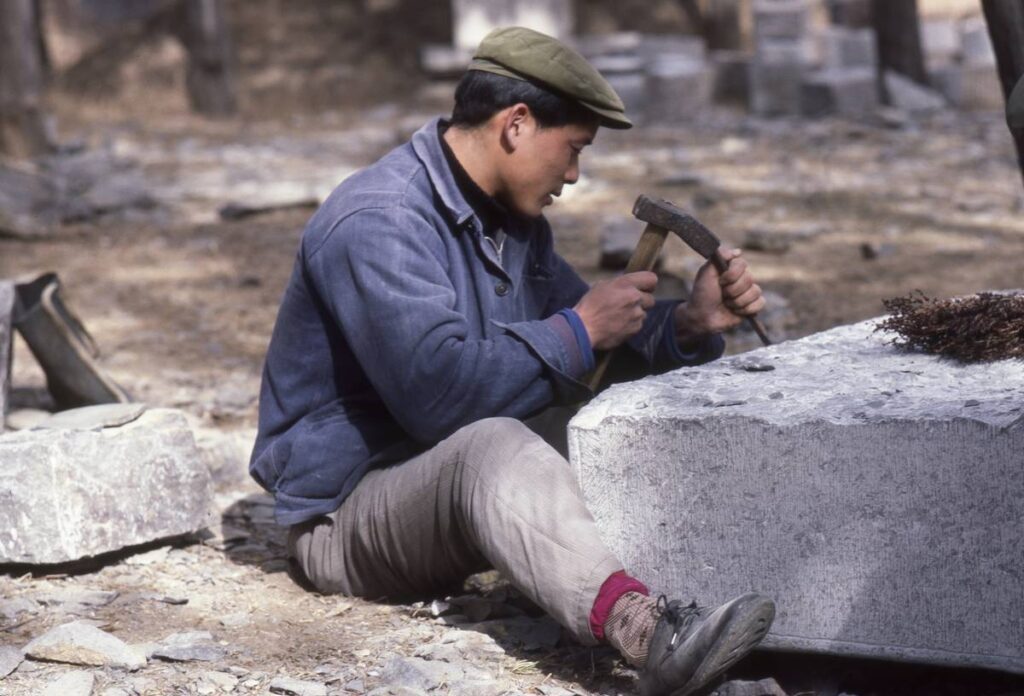

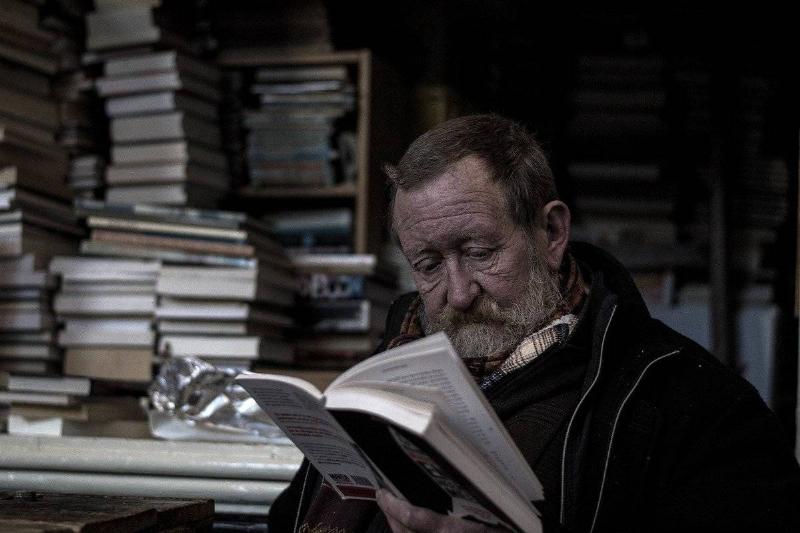

Engraving stone takes a long time. Because the boulder has 20 lines of text, it likely took at least a week. “It takes time to engrave like that, at least several days,” explains Michel Paugam, the local heritage and historical site manager.

ADVERTISEMENT

Whoever engraved the stone likely lived in the area. They also devoted plenty of time to the project, and it clearly meant a lot to them. That is why engravings like this are so rare.

ADVERTISEMENT

Whoever Inscribed It Knew What They Were Doing

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Several pieces of evidence suggest that the authors of this inscription were experienced with carving. For one, the rock is still visible above high tide, suggesting that the location was strategic. Also, stone engravings were not easy.

ADVERTISEMENT

“[The authors] had expertise in sculpting and the material,” says Paugam. “Writing we’re less sure; it’s possible someone else was telling the engraver what to do, but they were definitely from the profession. They knew how to etch into stone.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Perhaps They Were Soldiers

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Historians from Plougastel-Daoulas believe that the authors were likely soldiers. In 1787, the harbor was likely occupied by the military. Since the boulder is so close to a fort, they could have easily walked across the beach to work on the engraving.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Maybe people working in the fort had free time to come here in the evening,” Paugam theorized. “Perhaps they set up a campfire over there, a picnic over there, and one of them worked on the inscription.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Locals Historians Could Not Translate It

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Although experts from Plougastel-Daoulas uncovered the boulder, they could not translate it. They struggled to even identify the languages. “It might be a mix of several languages or even codes that would have been familiar to members of certain professions, particularly among sculptors,” says town council member Stéphane Michel.

ADVERTISEMENT

Because Brest was such an active port, sailors from all over the world stopped there. The local historians believe that the other language might have been Spanish, Catalan, or even Russian.

ADVERTISEMENT

For Help, They Created A Competition

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The mysterious engraving, which became known as the Rocher du Caro, baffled people across the world. After consulting every historian in the area, Mayor Dominique Cap still could not find a sufficient answer.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We’ve asked historians and archaeologists from around here, but no-one has been able to work out the story behind the rock,” he said. “So we thought, maybe, out there in the world, there are people who’ve got the kind of expert knowledge that we need. Rather than stay in ignorance, we said, ‘Let’s launch a competition.’”

ADVERTISEMENT

The Champollion Mystery of Plougastel-Daoulas

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In May 2019, the town council of Plougastel-Daoulas launched an international competition to decipher the engraving. They offered €2,000 ($2,200 USD) to the person who submitted the most likely theory. Every theory would be reviewed by a jury of town council members, historians, archaeologists, and Breton language specialists.

ADVERTISEMENT

The contest was called The Champollion Mystery of Plougastel-Daoulas after Jean-François Champollion, the linguist who helped translate the Rosetta Stone. After news outlets reported on the competition, it rapidly spread through social media.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Competition Received 61 Entries

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Shortly after announcing the contest, town council member Véronique Martin–who came up with the idea–received over 2,000 queries from people willing to participate. She sent out 60 applications within the first month in a half.

ADVERTISEMENT

By the time the contest ended, the jury had received 61 entries and over 1,500 pages of theories. Although most submissions were from France, others came from the United States, Belgium, the United Arab Emirates, and Thailand. They had a lot of material to review.

ADVERTISEMENT

What Were Some Of The Theories?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Within the 61 entries to read, the competition jury had many different ideas to read. One applicant studied the religions of families in that area. They proposed that the engraving could be a prayer to Jesus for protection.

ADVERTISEMENT

According to another theory, the 7’s were actually 1’s, and the engraving actually dated back to the 1100s. This would make the language Old Gaelic, not Old Breton. The jury studied all theories; they gave every one the benefit of the doubt.

ADVERTISEMENT

On Social Media, Users Were Pitching In

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

While historians wrote up comprehensive theories for the competition, people on social media were also throwing out ideas. On Reddit, users proposed explanations such as a Druidic religious site or a list of soldier names.

ADVERTISEMENT

Martin said that the contest “mainly attracted treasure hunters or people who are passionate about research and solving mysteries.” Internet users have contributed to historical mysteries in the past. However, these people were not officially entered into the contest; historians and researchers did.

ADVERTISEMENT

Finally, They Selected Two Winners

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In February 2020, the jury announced two winners in the French newspaper Ouest-France. Both would split the $2,000 reward. Mayor Cap said that both theories were “very similar.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Both winners proposed that the engraving was a memorial for a man who died. Each winner offered a slightly different translation, but they both fit previous ideas of soldiers at Crow’s Fort. The man who died was likely a sailor or soldier who passed away at sea, possibly in a shipwreck.

ADVERTISEMENT

Exploring The First Theory

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The first winning theory came from Noël René Toudic, an English teacher and Celtic language expert. He proposed that the writer was a semi-literate man who wrote in 18th-Century Breton. That would explain the letter and spelling inconsistencies.

ADVERTISEMENT

Toudic’s translation read, “Serge died when, with no skill at rowing, his boat was tipped over by the wind.” The numbers were the date when he passed away. But this translation makes little sense without the rest of Toudic’s theory.

ADVERTISEMENT

Toudic’s Explanation For What Happened

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

According to Toudic, the memorial was for a man named Serge Le Bris. He might have rowed during harsh weather or a storm, which explains how the boat was “tipped over by the wind.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The author–or at least, one of them–was Grégoire Haloteau. He signed the memorial with his last name and included the date: May 8, 1786. Toudic believes that Haloteau was a soldier, and possibly Serge too, given the boulder’s proximity to Crow’s Fort. But this is just the first theory.

ADVERTISEMENT

Exploring The Second Theory

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The second winners were a team: author Roger Faligot and comic artist Alain Robet. The two also proposed that the inscription was a memorial, but they had a different take than Toudic.

ADVERTISEMENT

Their translation read, “He was the incarnation of courage and joie de vivre. Somewhere on the island he was struck, and he is dead.” Joie de vivre means “zest for life” in French. Perhaps the author wrote a French phrase in Old Breton, making historians confused.

ADVERTISEMENT

This Version Of The Memorial Is More Angry

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Faligot and Robet suggested that the second language is Welsh, which is how they got that translation. They also said that the engraving might have been a response to foul play. The tone of the translation is more vindictive than Toudic’s.

ADVERTISEMENT

According to their theory, the man who died was a soldier who passed away during a battle. Perhaps his comrades got together and engraved a tombstone for him. Unlike the first theory, the deceased man was not necessarily a sailor.

ADVERTISEMENT

But One-Fifth Of The Engraving Is Still Untranslated

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The two winners of the competition did not completely solve the mystery. In fact, one-fifth of the engraving is still untranslated, according to Mayor Cap. This is due to many reasons, from the difficult languages to part of the inscription having eroded.

ADVERTISEMENT

“There is still a way to go to solve the mystery completely,” Cap told Agence France-Presse. The competition winners provided some context and purpose for the boulder, but whether or not they are correct remains to be seen.

ADVERTISEMENT

Plougastel-Daoulas Is Still Researching The Inscription

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Although a lot of research still has to be done, the residents of Plougastel-Daoulas are working on it. For now, locals are searching historical records for evidence of Serge Le Bris and Grégoire Haloteau, the two men mentioned in Toudic’s theory.

ADVERTISEMENT

Meanwhile, the town council will work on making the boulder more accessible to the public, according to Smithsonian Magazine. If more people see the engraving, more can solve it. Although there is much work to be done, Mayor Cap said, “We have made a great step.”