If Halsey’s The Great Impersonator project comes off as defensive, it’s because they’ve earned it. Their debut album, Badlands, came out almost 10 years ago, but Halsey has yet to be fully received with the kind of gravitas one might reasonably expect after a decade-long career. This goes back to the start. Early single “New Americana,” an earnest (for better or worse) song about a particular kind of millennial experience, was received as Girls-esque parody. A claim went around that Halsey identified their sexuality and neurodivergence with the flippant label “tri-bi,” a rumor Halsey called “the dumbest shit I’ve ever heard.” And scads of early press profiles likened them to “a millennial grown in a lab” and “a superstar you can own” – dismissive, boomeresque takes that have nevertheless stuck to Halsey ever since. Even their creative breakthrough, the 2021 Trent Reznor collaboration If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power, had a nagging undercurrent of reality: coincidentally or not, their music was never fully taken seriously until a male auteur got involved.

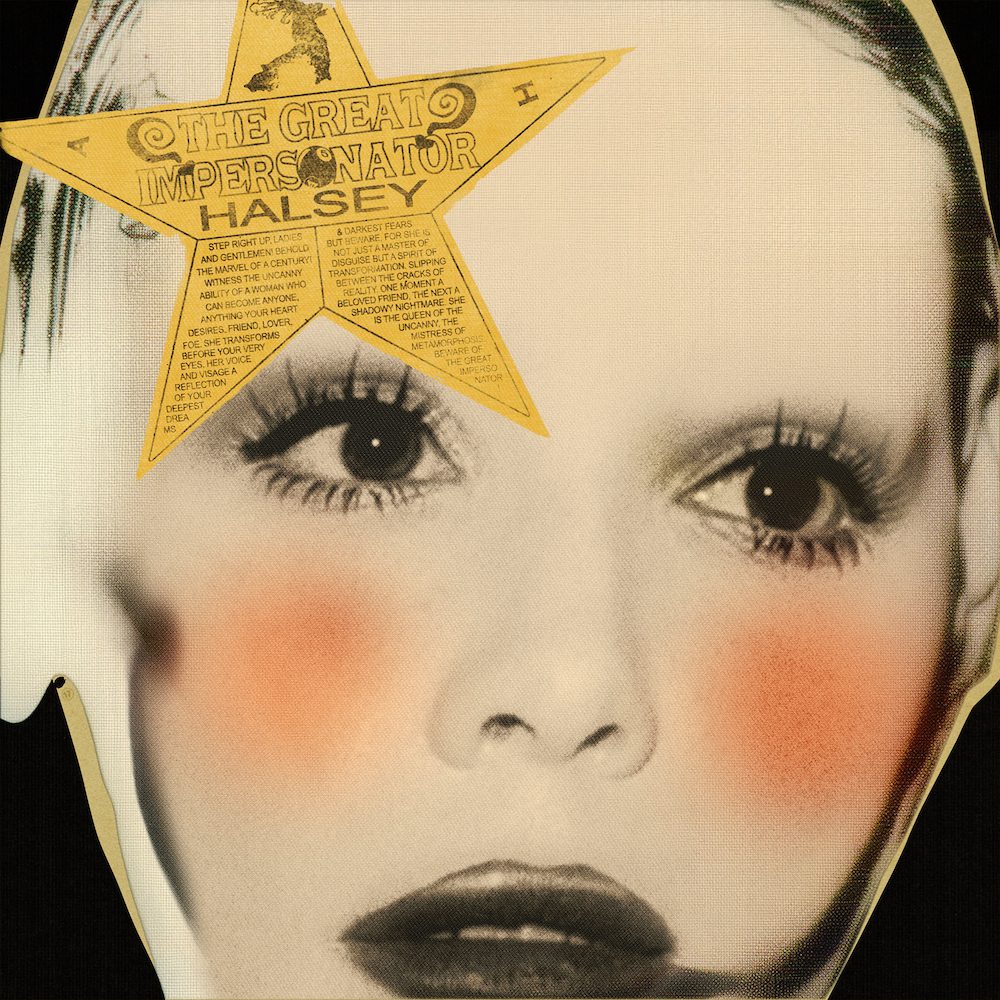

The Great Impersonator, Halsey’s follow-up, is their attempt to get ahead of all the criticism. Rather than try to beat the chameleon allegations, they leaned into them, promoting the album with a pop-Cindy Sherman photography series in which she dressed up as the musicians who inspired particular songs. This is all too easy to read as a pure gimmick: the perfect blogbait for Halloween costume season! But Halsey is making actual points here. The artists they chose for the project – e.g., Kate Bush, Aaliyah, PJ Harvey – are not arbitrary. They’re artists with big institutional credibility (and yes, this is partly Halsey’s bid to join their ranks someday). But they’re also pretty personal choices. It makes total sense that Halsey, a New Jersey native, would idolize Bruce Springsteen. The late Dolores O’Riordan famously sang with the vocal affectations now called “cursive voice” and was dismissed for them just as much at the time; you can hear those stylings in Halsey’s vocals, and it may be a deliberate influence. And Amy Lee of Evanescence, who is not normally included in such pantheons, has gotta be a pick from their formative teenage years.

Most importantly, most of these artists are infamous for being musicians that rising artists are frequently compared to, generally unfavorably. Some of them were even pitted against each other; also on the list is Tori Amos, who had to fight off plenty of accusations in her early career that she was a Kate Bush impersonator. Basically, Halsey’s tired of being compared to damn Britney Spears (and everyone else). The catch, of course, is that by associating each song with another artist, Halsey invites listeners to do just that. It’s a reductive way to hear the album – but it’s both unavoidable and textual, so let’s just do it. If Halsey’s grunge snarl on “Dog Years” doesn’t immediately evoke Polly Jean Harvey, the whispered, menacing, quasi-sexual chorus makes the “Down By The Water” connection obvious. “The Great Impersonator” isn’t anywhere near the wild whirl of a Björk single, though the strings do hint at “Human Behavior” and “All Is Full Of Love”; but Halsey quirks up her vocal in an honestly pretty accurate impression. Halsey’s “Lucky” just interpolates the Britney song outright.

Other connections are more vibes-based: “Panic Attack” and “Hometown” are slinky and twangy like Stevie and Dolly respectively, and the resemblance ends there. Some baffle me completely. As a lifelong Kate Bush stan, I’m not sure what in “I Never Loved You” is meant to be Katelike – the layered background vocals at the end are faintly reminiscent of the Trio Bulgarka spots on The Sensual World, maybe? “Arsonist” has Fiona Apple’s swagger and characteristic turns of phrase – “Your human starter kit came incomplete” is the kind of pileup of crunchy syllables Apple would make a meal of. But the arrangement shares little with Apple’s catalog, except that producer Thelonious Martin’s drum loops sound like something off the Mike Elizondo version of Extraordinary Machine. The actual Tori Amos ballad on The Great Impersonator, despite what the credits are telling you, is “Darwinism”; the ominous minor-key piano line and Halsey’s plaintive, hovering vocal recall Tori’s late-career slow burns like “Smokey Joe” and “Starling.” The withering “Life Of The Spider,” meanwhile, sounds like someone trying to write a Tori Amos ballad based on a vague recollection of pianos and feminine pain. (To be fair, the track is labeled as a draft and obviously is one.)

Decoding all these impressions is all well and good, a fun ARG for Lilith Fair enjoyers; but if you get too deep into the rabbithole, you’ll miss what else The Great Impersonator is doing. If they wanted to mimic other artists exactly, there’s AI technology for that. Instead, Halsey sounds like Halsey no matter what vocal costuming she adopts. (Just saying, this persistent thing where Halsey keeps sounding like Halsey would seem logically at odds with the accusation that they don’t have a coherent musical identity.) More pertinently, Halsey’s themes aren’t drawn from their impersonatees. The record continues the confessional songwriting threads they’ve pulled at for years: the tolls of growing up amid a fucked-up family, living as a celebrity among tabloid gawkers and parasocial priers, longing for but struggling to claim a solid sense of self, and generally pulling oneself out of one dark place after another, alone.

Other themes are new. Halsey had a son with screenwriter Alex Aydin in 2021; the two broke up in 2023, making her a single mother. And earlier this year, Halsey revealed that in the interim between albums, they were also diagnosed with lupus and a rare T-cell disorder, and were subsequently in and out of hospital: “Long story short, I’m lucky to be alive.” The Great Impersonator is a direct response to these challenges: the stark necessity of being there for your child when you haven’t been there for yourself, and the paradox of spending years wanting to die and then facing the real, looming prospect of death. Nowhere is this more explicit than the thematic core of the record, the “Letter To God” trio.

Each of these tracks is a vignette from a different point in Halsey’s life (maybe fictionalized, maybe not) and a variation on one hook. The arrangements are not musically showy or fleshed-out, nor the most clear homages to their respective artists; the point is to get out of the way of the lyrics. “1974” is an impulsive childhood prayer, prompted by watching a classmate with leukemia be loved and cared for: “Please, God, I wanna be sick.” The song is authentically childlike – among kid-Halsey’s observations is that their friend “didn’t have to clean his room, it was enough to be alive” – and an, uh, brave thing to put on record. But the childishness exists to directly set up “1983,” in which Halsey revisits this incident after her diagnosis: “I never would have said it if I knew I’d have to wait until the moment I was happy, then it all disintegrates.”