It doesn’t actually matter that Ghostface Killah isn’t saying “seven doulas” and “rotisserie roasts” on “Nutmeg.” Because he is verifiably talking about “seasoned giraffe ribs,” “nasal drip,” and an invitation to count the number of veins on his dick. The phlegmy RZA shows up to praise a woman’s armpit and boast about period sex. This is rap at its most untethered; other than the beat, the verbal content is completely free. It’s Ornette Coleman, it’s Sonic Youth, eventually, it would come to be Lil Wayne.

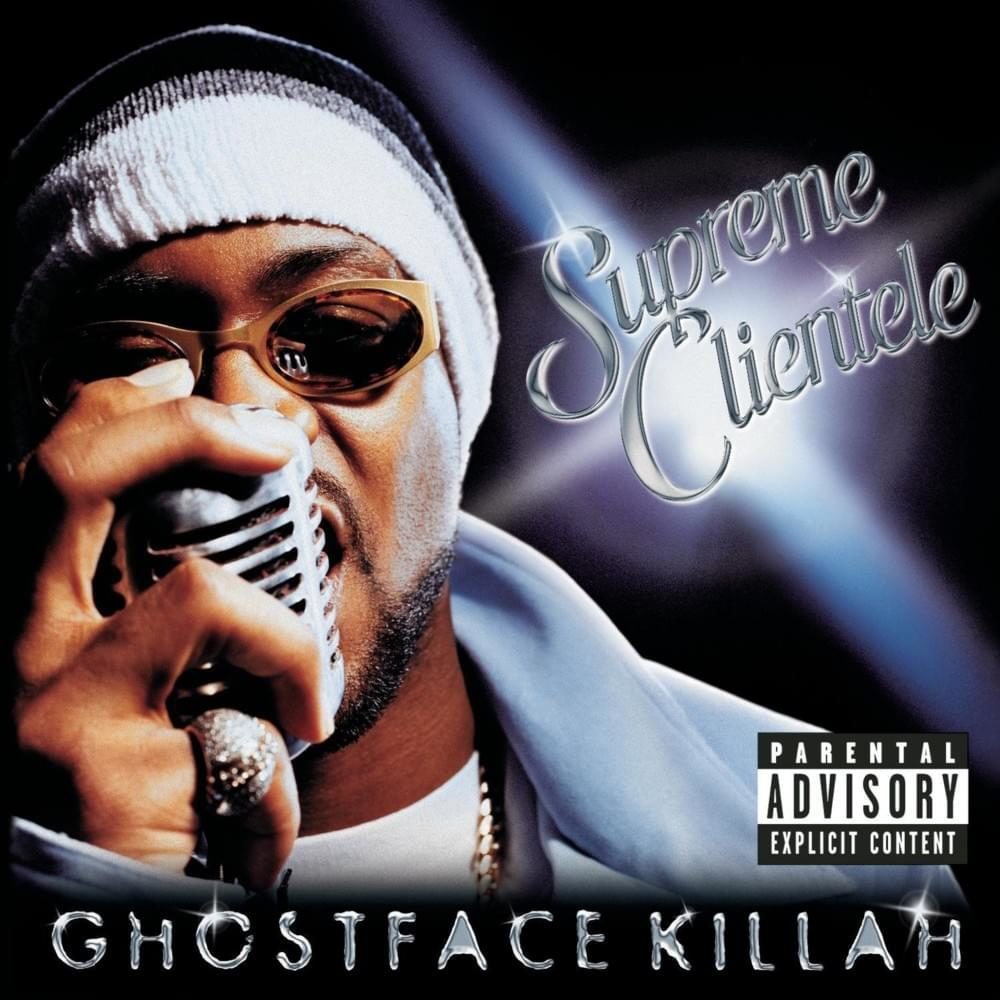

Twenty years later, some of the mysteries of Ghostface Killah’s second solo album, Supreme Clientele, still remain unsolved, even the packaging. Whose idea was it to make the CD’s inner tray sparkly and silver (awesome) or to include two different 14-song tracklists, one on the back cover, one in the booklet, for the 21-track album (a headache). The booklet one is especially laughable because it’s numbered, falsely, and includes things out of order (“We Made It” does not come before “Malcolm”) or nonexistent (there is no such song as “In the Rain” or “Deck’s Beat,” even if Robert Christgau did call the latter the funkiest thing on the record). Wu-Tang kids, of course, love figuring shit out and did not complain, even though by 2000, they were oversaturated with Wu Wear, Killa Bees, and other distractions from the true reasons for their fandom, which peaked about five years earlier. Supreme Clientele, their reward for sticking around, is now possibly the most respected rap album of the 2000s. But it made a strong case that it was fucking with us.

Tony Yayo of G-Unit, whose leader 50 Cent was threatened in Raekwon’s pitched-down “Clyde Smith” skit here, infamously boosted Wu associate Superb’s claim that he wrote, “the majority” of Supreme Clientele. It’s fun to imagine how Superb’s version of this story could’ve even gone: “You should describe your car as ‘booger-green’ right here.” “That’s gold.”

Nice Like Van Halen: Ghostface Killah’s Supreme Clientele Turns 20

The real narrative from this time has been largely unpacked. Between his auspicious debut Ironman and its beloved follow-up, Ghost was suffering from increasingly severe medical complications that finally got pinned down as diabetes (ever the realest surrealist, in 2009 he’d rap “If my sugar high, my dick don’t get up”). The only doctors he trusted treated him while he stayed in the West African nation of Benin, where he wrote “Nutmeg,” “One,” and “Buck 50” with no beats, running water, or floors in the village huts. When he returned to the U.S., someone slashed the rapper’s tires and after the resulting scuffle, he was pressured to take a plea for attempted robbery, which he did. During his four-month prison stay, he told this very publication that the prison guards refused him his insulin. Plenty of rappers could’ve written about the blues from these experiences. Dennis Coles instead shone a light on the yellows, greens, and purples. “It’s like a box of crayons, or a nice fruit bowl,” he later said of this album in Complex.

You can always see, smell, and especially, taste his rhymes. Strawberry kiwi, ravioli bags, “rhymes is made of garlic,” “your shit is scampi,” “Mrs. Dash,” “chicken and broccoli, Wallys taste stink.” (Why was his sidekick Raekwon called the chef again?) When asked why he boasted “This rap is like ziti,” Ghost said, “That was my best food back then.” One of the best lines on the album, an 18-word tour de force that surely Hemingway could appreciate, is “We at the opera/ Queen Elizabeth rub on my leg/ Had ketchup on her dress from a Whopper.” Or the eight-word “Slapped the pastor, didn’t know pops had asthma.” Or the three-word “dicking down Oprah.” At times, the man just seems to be taking inventory of his entire vocabulary: “He bantamweight, fronting majorly.” His cohorts get into the spirit; on “Wu Banga 101,” GZA compares his strength to an ant’s, and on “Stroke of Death,” RZA invokes “Oh! Susannah.” It’s almost certainly the album where the Wu-Tang reaches the epiphany that their desire to encrypt their meanings means they’ll have to have a lot more fun dreaming up codes. Why do you think they call rap circles a cipher?

Being in the Wu, Ghost is foremost an entertainer, hence the comedic suspense of the music pausing in “Woodrow the Base Head” so the title character can offer nine whole bucks for some rock. And unlike an esoteritician like Aesop Rock, Tony Starks’ voice betrays no apology or self-consciousness for his sheer density of unpacked thought. His pure conviction can sell a childhood memory of a girl getting his “ding-a-ling” hard or make wearing “jean jackets and turtlenecks” sound like the coolest decision on “Stay True,” one of many sub-two-minute tracks that Ghost declined to identify as a song or an interlude. A couple of decades later, hip-hop tracks that brief are finally the norm; one just broke the Hot 100 as the longest-running No. 1 song of all time (given, this was largely due to its 2:37 form, but still). The album’s influence isn’t always so subtle. “Catch me in the room eating grouper” from “Buck 50” was a hot line that Action Bronson made a career of. (Made hotter by the fact he set up “grouper” with “supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” forward and backward beforehand.)

Didn’t Know Betty Crocker Had Two Nines: Ghostface Killah’s Supreme Clientele Turns 20

This would all really mean nothing if the music wasn’t great. Ghost’s obscure producers brought in plenty, but RZA mixed it all for a sturdy melodic coherence that let the freaky words be themselves. Just Blaze would come to build on the smothering squeal of “Saturday Nite” and the superhero-theme Solomon Burke horns of “Apollo Kids,” returning the favor from both on 2006’s explosive “The Champ.” The overall effect of the grating scratch loop “Stroke of Death” is as psychedelic as anything Andre 3000 has ever dreamed up; Chris Rock proudly said the track “makes you want to stab your babysitter.” And “Mighty Healthy” is beauty worthy of Endtroducing…DJ Shadow with its sloshing-rainboots beat and Boards of Canada-worthy “hey” cut into every eighth bar.

Towards the end, Ghost decides to experiment with narrative coherence (“Child’s Play”) and something resembling conventional club music (“Cherchez LaGhost”) even though it’s the starkest (if not Stark-est) thing on the record. Regarding the latter, you do have to love how Ghost or his record company decided the formula of remaking a Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band hit to include the word “Ghost” — was crucial to repeat for 2001’s Bulletproof Wallets, where “Sunshower” became “Ghost Showers.”

Because the sort of hip-hop head who worships Supreme Clientele rarely sits still for rap careerism, it’s worth noting that few artists of any genre had a run like Ghost’s from 1996 to 2009. This includes the heralded but somewhat forgotten masterpiece Fishscale as well as the gutsy, radically inspired Ghostdini: The Wizard of Poetry in Emerald City, full of “Paragraphs of Love” in all permutations: a prison apology, a pregnant object of affection, and the FIOS installation guy fucking his wife. (With Ghost’s Def Jam deal about to expire, he literally said “fuck it.”) Supreme Clientele was part of a much bigger winning streak that’s less fun to contemplate because its other highlights weren’t comparable to, like, Finnegans Wake. But Ghost (as well as MF Doom, not coincidentally a big Ghost collaborator himself) is deservedly praised for popularizing free association in hip-hop for this work. Few genres have an architect as impressionistic and detailed as the guy who took such beautiful pains to reinvent rap slang from a curious number of Italian foods.

And yet the greatest thing about Supreme Clientele is the pervading fantasy that all this code can be cracked by the average stoner, that this intensely exciting slice from one excellent rapper’s shared consciousness can be enjoyed even more than it already is. “Supreme Clientele” is the name/slogan of several barbershops in the Northeast; I didn’t discover this myself until I stopped for Jamaican food in Camden, New Jersey. “Nutmeg,” its opening salvo and zonked-out mission statement, was given a beat by Black-Moes Art, Ghost’s barber, who never did anything else of note. Not all of the album’s stories have other stories tucked away inside every footnote, typo, and dubiously cleared sample. But enough of them do make you wonder if there’s a limitless universe, just like the Wu’s beloved Marvel comics and religious texts and martial arts films. Few albums prompt so many fun questions, and not since jazz’s heyday has an artist so powerfully suggested that perfection is open-ended.