In The Number Ones, I’m reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart’s beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present. Book Bonus Beat: The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal the History of Pop Music.

I know. I know! Believe me, I’m right there with you. Kenrick Lamar did not consult me on when he should drop his new album GNX. In fact, he threw my writing schedule into chaos. I have to work extra shifts at the content factory because of this man’s timing. Kendrick is almost certainly not aware of this column. He might’ve never seen or read the word “Stereogum” in his life. Kendrick’s buddy Jack Antonoff is a different story, but I would not presume to imagine that Antonoff told Kendrick to release his new earthshaking blockbuster record a few days before the Number Ones column on “Humble.” That would be too weird. I am not that important.

It’s not the first time this has happened, right? The universe moves in mysterious ways, and occasionally the timing of this column intersects with the real world in dizzying, unpredictable ways. It could be a total coincidence, but I would prefer to believe that I am subconsciously locked in with some of the uncanny forces that define our lives. It’s a little scary, but I’m getting used to it. When you’re as tall as me, you’re closer to God. Anyway, let’s get into the column that I started writing before a masterful new Kendrick album suddenly appeared on my phone. Pretend you didn’t read these two paragraphs. Pretend the next sentence is the lede.

The second that you heard the piano, you knew what time it was. In 1988, the great Queens rap producer Marley Marl cut up the pounding riff from Otis Redding’s “Hard To Handle,” setting it to some hard, minimal drums and doing almost nothing else to decorate it. Marley brought in four of the hardnosed, unflappable rappers from his Juice Crew collective — Masta Ace, Craig G, Kool G Rap, and Big Daddy Kane — to flex effortlessly over that beat, sometimes throwing echo on their voices. Nobody bothered to come up with a chorus because a chorus wasn’t the point.

The resulting single was called “The Symphony.” It got a fun Old West-themed video, but it never came anywhere near the Hot 100. The late ’80s marked the very beginning of rap’s crossover era. Rappers scored a few Hot 100 hits in that moment, but they had to try really, really hard to get there. When Marley Marl and those Juice Crew guys made “The Symphony,” that wasn’t what they were trying to do. They were just trying to make the hardest record on earth, and they succeeded. “The Symphony” helped establish the convention of the posse cut, the chorus-free workout where a bunch of rap titans compete to see who can say the coldest shit, and it stands to this day as one of the great examples of the form.

[embedded content]

Rap moved in about a million aesthetic directions after “The Symphony,” but the primal power of that minimal gut-punch drums-and-piano beat never went anywhere. “The Symphony” almost certainly wasn’t the first rap record to combine a hard-ass piano with some hard-ass drums, and it was far from the last. That combination serves as an instant back-to-basics statement, a mental signal that somebody is about to come in and talk some shit. In May of 2016, for instance, the Pittsburgh rapper Jimmy Wopo used some hard-ass piano and drums to introduce himself on his song “Elm Street.” Wopo, born nine years after the release of “The Symphony,” never became a star, and he was gunned down in 2018 at the age of 21. But the electric jolt of “Elm Street” lives forever.

A year after Jimmy Wopo released “Elm Street,” Kendrick Lamar went to the tough minimalism of that drums-and-pianos combo on his instant-blockbuster single “Humble.” In the moment, some Twitter commentators tossed out the idea that Kendrick was trying to ride Jimmy Wopo’s wave. I don’t doubt that Kendrick, a tireless fan and advocate of street-rap, heard and loved “Elm Street.” But when Kendrick heard those pianos, he heard something else. In 2017, Kendrick told Rolling Stone, “All I could think of was ‘The Symphony’ and the earliest moments of hip-hop, where it’s complex simplicity, but it’s also somebody making moves. That beat feels like my generation, right now.”

Complex simplicity, but also somebody making moves. That’s beautiful, and it’s also accurate. Before he heard that piano, Kendrick Lamar had already made plenty of moves — enough that he was widely considered his generation’s greatest rapper, a voice of rare depth and virtuosity who could still sometimes cartwheel into mainstream consciousness if everything lined up exactly right. When he heard that piano, Kendrick became something else. He went into Juice Crew mode, or an updated version of Juice Crew mode, and he tore that motherfucker up. “Humble” did not come out in 1988. It came out in 2017, when a hard-ass rap record might just vault its way to the top of the Hot 100.

[embedded content]

Kendrick Lamar wasn’t always a pop star. That can’t be overemphasized. Kendrick Lamar has been in this column before, but he didn’t get here on his own. In 2015, Taylor Swift got Kendrick to rap on her “Bad Blood” remix. This was a decision made for prestige-bait and stunt-casting reasons — Swift recruiting a profound and beloved rapper to join her noisy, hammering pop-star diss track and, more importantly, its CGI-slathered celebrity-parade video. It was not made for musical decisions. Kendrick Lamar did not get the chance to cut loose on “Bad Blood.” He might not have even had the chance to be himself.

I’m sure Taylor Swift loved Kendrick Lamar, that she still loves Kendrick Lamar. Lots of pop stars love Kendrick Lamar. I can still remember when Lady Gaga stood off at the side of the third Pitchfork Music Festival stage to watch Kendrick’s set in 2012. When Kendrick appeared on “Bad Blood,” he was coming off the release of his complex, layered 2015 opus To Pimp A Butterfly, probably the consensus critical pick for the decade’s best album. To Pimp A Butterfly was not a blockbuster. It only went platinum once, and its highest-charting single, the pre-release track “i,” peaked at #39. But the record loudly announced its importance, and Kendrick Lamar became the type of rapper that Barack Obama might cite as his favorite.

In 2016, Taylor Swift’s 1989 won the Album Of The Year Grammy over To Pimp A Butterfly, continuing Kendrick Lamar’s Beyoncé-esque knack for getting big Grammy nominations and then losing those Grammys in ridiculous ways. No matter. Kendrick Lamar was the people’s champ, and “Bad Blood” also showed that he was at least willing to rap on cheesy pop songs. In 2016, Kendrick made a similarly lightweight appearance on Maroon 5’s #6 hit “Don’t Wanna Know.” (It’s a 5.) That was part of a run of pop features, as Kendrick popped up on stuff like Sia’s “The Greatest,” Beyoncé’s “Freedom,” the Weeknd’s “Sidewalks,” and Travis Scott’s “Goosebumps.” (“Goosebumps” is a bit of an outlier there, since Travis Scott is at least a rapper, but he’s not a Kendrick Lamar type of rapper. He’ll be in this column before long.) None of those songs were huge hits, and none of them really sounded like Kendrick Lamar songs, but all of them charted. On those songs, Kendrick is a supporting player on his way to leading-man status.

At the same time, Kendrick Lamar was putting on incendiary awards-show performances and trading bars with rapper’s-rapper types like Danny Brown. In some of his TV appearances, he’d bust out dizzying songs that weren’t even released. Kendrick’s To Pimp A Butterfly follow-up was a nakedly uncommercial move: Untitled Unmastered, a 2016 collection of TPAB castoffs that were plainly not made with the pop charts in mind. The record debuted at #1 on the album chart — a clear sign of the goodwill that Kendrick had amassed — but barely any of its songs made the Hot 100. (The highest-charting of them was “untitled 02 | 06.23.2014.” — they all have titles like that — which peaked at #79.)

In the stretch after To Pimp A Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar sent some mixed messages out into the world. That’s pretty much what he’s always done. Again and again, Kendrick uses his records to present himself as a flawed and contradictory human being, not as the messianic all-substance rap figure that so many people clearly want him to be. He kept his name in the mix by rapping on fluffy pop singles, but he didn’t seem like he wanted to be a pop star himself. Instead, he made thorny and insular music, carrying himself as a cult artist on the largest possible level. It all went out the window when he heard the “Humble” piano.

The “Humble” piano came from Mike Will Made-It, the big-deal Atlanta rap producer who’s already been in this column for his work on Rae Sremmurd’s “Black Beatles.” Actually, it came from two producers: Mike Will and Asheton “Pluss” Hogan, a Canton, Ohio native who moved to Atlanta when he was a kid. Mike Will and Pluss met in a high school math class, and Pluss became one of the in-house producers at Will’s EarDrummers label. Pluss had co-producer credits on Mike Will hits like Lil Wayne’s Drake/Future collab “Love Me” and Beyoncé’s “Formation.” Pluss co-produced “Humble” with Mike Will, and he joins Will and Kendrick Lamar as one of the song’s three co-writers. But Pluss isn’t an established name brand, so he doesn’t usually get mentioned when people talk about “Humble.” Let’s change that.

Mike Will and Pluss made the “Humble” beat quickly in a late-night session. Pluss told Billboard that it took them 20 or 30 minutes and that they “really cooked it up just for fun.” Pluss didn’t find out that Kendrick Lamar had recorded over that beat until months later, when the song came out. To hear Mike Will tell it, though, he had big plans for that beat. Mike told NPR, “I knew that beat was going to capture a moment. It just felt real urgent. I made that beat [last year] when Gucci Mane was getting out of jail; I made it with him in mind. I was just thinking, damn, Gucci’s about to come home; it’s got to be something urgent that’s just going to take over the radio. And I felt like that beat was that.”

Gucci Mane, the Atlanta institution who gave a teenage Mike Will his big break, did not use that beat for whatever reason. I’m sure he could’ve gone hard on it, but it doesn’t really sound like a Gucci beat, at least to me. Gucci excels when a track has a tingly little melody and a druggy, aqueous float. That’s not “Humble.” The “Humble” beat has an old-school ’80s intensity, an unforgiving sparseness. Gucci is old enough that he went to see Run-DMC as a kid, and he knows how to rip up an old-school trunk-rattler, but it’s not his preferred lane. For Kendrick Lamar, coming off of a layered and experimental album, a beat like that was a perfect vehicle for a hard zag.

Before Kendrick made “Humble,” he and Mike Will had known each other for years, but they hadn’t recorded much together. Before he met Kendrick, Mike Will produced “My Hatin Joint,” a track that Kendrick’s TDE labelmate and frequent collaborator ScHoolboy Q included on his 2012 album Habits & Contradictions. (ScHoolboy Q’s highest-charting lead-artist single is the 2014 BJ The Chicago Kid collab “Studio,” which peaked at #38. Q also guested on the Macklemore/Ryan Lewis song “White Walls,” which peaked at #15 in 2013.) Kendrick was already an ascendant force by then, but Mike Will says that he hadn’t heard of Kendrick when Q brought him to the studio in Atlanta.

Kendrick and Mike Will hit it off, and they talked about making music together for a long time. Mike says that he submitted some tracks for To Pimp A Butterfly but that “they definitely weren’t the right vibe,” which seems very true. The first time that they ever worked together was when Kendrick rapped on “Buy The World,” a song from Mike’s 2014 mixtape Ransom that also featured Future and Lil Wayne. (Since things seem to be brewing on that front, it’s notable that Kendrick handily outrapped Wayne.) The second was “Humble.”

Kendrick told Rolling Stone that the entire idea for “Humble” came from the beat: “The first thing that came to my head was, ‘Be humble.’” On the “Humble” hook, Kendrick spits that line out as a warning. An army of multi-tracked Kendricks chants, “Hol’ up, bitch! Hol’ up, lil bitch!” Up front, another Kendrick repeats the refrain again and again: “Sit down. Be humble.” That line is probably best understood as a message to the rest of the rap world in general, and maybe to Drake in particular. (Even back then, tons of people assumed that every pointed Kendrick line was aimed at Drake.) I think that’s probably what Kendrick meant, but Kendrick can mean multiple things at the same time.

Kendrick told Rolling Stone that he was really talking to himself on that hook: “It’s the ego. When you look at the song titles on this album, these are all my emotions and all my self-expressions of who I am. That’s why I did a song like that, where I just don’t give a fuck, or I’m telling the listener, ‘You can’t fuck with me.’ But ultimately, I’m looking in the mirror.” So he’s reminding himself to be humble while also informing the rest of the world that we can’t fuck with him. That dichotomy runs deep in the Kendrick discography. He’s incisive about his own personal failures, but if you come after him, he will annihilate you.

“Humble” is mostly devoted to Kendrick flexing hard. The track opens with a distorted guitar riff and Kendrick making a singsong proclamation: “Nobody pray for me! It been that day for me!” (For whatever reason, the video version changes that first line to “wicked or weakness, you gotta see this” but doesn’t alter anything else.) When the beat kicks in, it’s absolutely colossal — the piano hammering away, the 808 kicks and handclaps hitting like thunk thunk thunk thunk thunk. Kendrick flashes back to being young and literally hungry — “I remember syrup sandwiches and crime allowances” — immediately locking into his world-conqueror flow.

When Kendrick Lamar is really on, he can sound like chaos embodied. The first time I saw Kendrick live, in what I’m pretty sure was a half-empty college cafeteria, I tweeted something about how he’s got a short man’s intensity, and I meant that as a big compliment. Kendrick is a small guy, and he’s got this nasal upper-register honk of a voice. He can do a lot of things with it, but he usually exaggerates that quality to a near-comical degree. At his best, he lets the beat take the lead, tumbling over the track with instinctive ferocity and landing on oblique, locked-in cadences that nobody else would attempt. He sounds like he’s making it up as he goes along, but then he says something that lodges in your memory forever — “My left stroke just went viiiii-ral!” — even if you’re not convinced that it actually means anything.

“Humble” is one of the hardest, simplest tracks of Kendrick Lamar’s entire career, but its simplicity is complex. Kendrick has the rare gift of describing street activities in ways that you never heard or considered before: “I get way too petty once you let me do the extras/ Pull up on your block then break it down, we playin’ Tetris.” He describes his own elevated stature and shames his lean-addled peers in a couple of quick, masterful strokes: “This that Grey Poupon, that Evian, that TED Talk! Watch my soul speak! You let the meds talk!” Sometimes, he plays word games. Sometimes, he goes direct, throwing out the double entendres so that you can feel the shit: “I make a play, fuckin’ up your whole life.” You can’t say he didn’t warn you.

There are references galore on “Humble”: Showtime At The Apollo, Richard Pryor’s afro, the highest note in the human vocal range. Kendrick digresses long enough to talk about beauty standards and PhotoShop, but he cuts it off quickly enough that it doesn’t come off as preaching. He tosses off a quick allusion to his friendly relationship with Barack Obama and to the newly imperiled Affordable Care Act. Maybe Kendrick understood that the country could use some hard-ass rap anthems at the chaotic beginning of a Trump presidency. At least we’re repeating some of the good parts of history, too.

If Kendrick is really telling himself to be humble on “Humble,” you can’t tell. He doesn’t sound humble. He sounds like he’s got power bursting out of him and like he wants to light the world on fire. He’s a rap titan at the peak of his powers, and it’s a blast just to hear him cut loose, especially after the jagged experiments of To Pimp A Butterfly. That’s what made it such an ideal introduction to Damn, the 2017 album that, for once, didn’t have much of an overarching concept. There are lots of different sounds and ideas at work on Damn, and its unmoored sense of freedom is one of its greatest strengths. Among other things, Damn represents Kendrick falling back in love with rap itself. That’s what he does on “Humble.”

“Humble” itself was an announcement, and the video magnified it. Kendrick’s videos have always been visionary auteurist works, and he’s always played a big part in their construction. For “Humble,” Kendrick and his longtime business partner Dave Free, credited as the Little Homies, co-directed alongside Dave Meyers, one of the kings of bugged-out big-budget music videos. Kendrick had never worked with Meyers before “Humble,” but the clip has some of the inventive, cinematic silliness that Meyers brought to his old Missy Elliott collaborations like “Get Ur Freak On” and “Work It.”

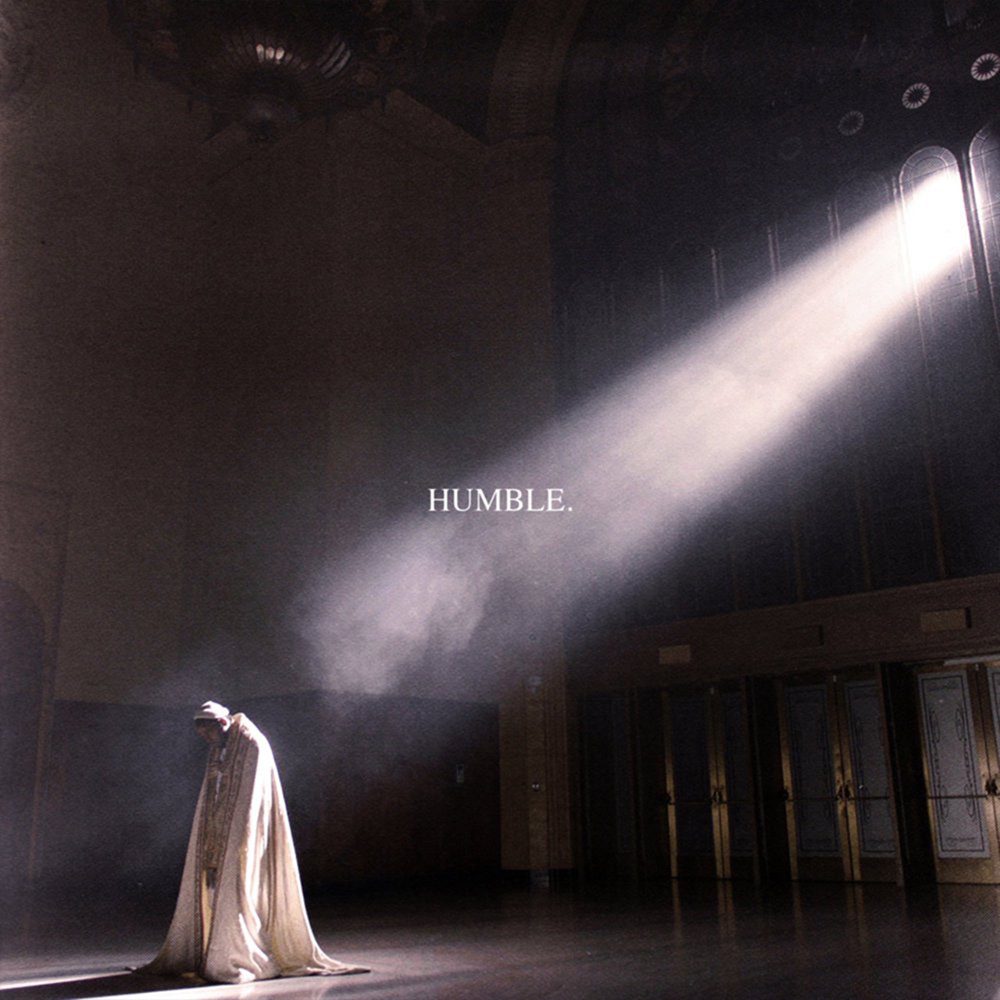

The first shot in the “Humble” video is the image that you see in the single cover art above: Kendrick Lamar, dressed up in papal finery, dramatically posed in a beam of light. From there, it’s a fly-ass fever dream. It’s Kendrick riding his bike around in cartoonish psychedelic drone shots or mean-mugging with his friends while the camera pulls impossible, disorienting moves. He stages Da Vinci’s Last Supper as a living diorama. He stands amidst a sea of bald bobbing heads, some of them popping up to mouth out the hook. He hits golf balls off the roof of his car in the LA River. He pounds his chest as sniper-scope red dots appear all over his body. He lights his head on fire. It’s awesome. I couldn’t stop rewatching it.

When Kendrick first recorded “Humble,” the idea was for Mike Will to include it on his compilation album Ransom 2. Kendrick’s team told him that he needed to keep the song, and Mike says that he told Kendrick, “Bruh, you definitely should keep it, and you should use it as your single.” Instead, Kendrick appeared on a different Ransom 2 track, teaming up with Mike’s “Black Beatles” collaborators Rae Sremmurd and Gucci Mane on a fun song called “Perfect Pint.” The “Perfect Pint” video, a Fear & Loathing In Las Vegas pastiche, actually came out on the same day as the “Humble” clip. “Perfect Pint” didn’t chart, but it probably helped build up the sense that Kendrick Lamar season had officially arrived.

[embedded content]

“Humble” debuted at #2, and it rose up to the #1 spot two weeks later, finally dethroning Ed Sheeran’s “Shape Of You.” Unlike “Black Beatles” and the Migos’ “Bad And Boujee,” the two decidedly non-pop rap bangers that preceded it at #1, “Humble” didn’t need meme assistance to top the Hot 100. Instead, the thing that pushed “Humble” to the top was the release of Damn, which came out two weeks after the single.

Damn was a big deal. Kendrick Lamar got a lot of help from Mike Will, one of the kings of the then-dominant Atlanta trap sound, without ever sounding like he was trying to ride Atlanta’s wave. Instead, Kendrick found ways to fit that Mike Will style into his own aesthetic patchwork, much as he does with Mustard production on the new GNX album. The Mike Will beats share space with a fascinating team of producers, including the Alchemist, 9th Wonder, BadBadNotGood, James Blake, Cardo, Greg Kurstin, Terrace Martin, longtime collaborator Sounwave, and future Number Ones artist Steve Lacy. There are no guest-rappers on Damn, but foundational mixtape figure Kid Capri bellows all over the record. Rihanna, already on her way out of the pop sphere, shows up on “Loyalty,” a single that peaked at #14. Weirdly enough, U2 also pop up on the otherwise-hard Mike Will production “XXX,” though Bono is only barely on that one. (“XXX” peaked at #33.)

Damn got near-uniformly rapturous reviews, including one from me, and it moved more than 600,000 album-equivalent units in its first week. That first week pushed “Humble” to #1, and Kendrick’s song “DNA” debuted and peaked at #4. (It’s a 9.) That’s another anthemic Mike Will production with a mini-masterpiece of a music video — this time pairing Kendrick with Don Cheadle. (At the time, Kendrick took to wearing martial arts outfits and calling himself Kung-Fu Kenny, and Cheadle played a character by that name in Rush Hour 2.) Kendrick Lamar videos are the best. As I write this, he hasn’t dropped any videos for any GNX tracks yet. I hope we get some.

[embedded content]

Damn ultimately went triple platinum, which means it did about three times as well as To Pimp A Butterfly and about the same as Kendrick’s previous album Good Kid, m.A.A.d. City. At the 2018 Grammys, Kendrick opened the show with a fire-eyed mini-set that featured U2 and Dave Chappelle, and then he lost Album Of The Year to Bruno Mars’ 24K Magic — typical Grammy bullshit. (Bruno Mars has been in this column a bunch of times, and he’ll be back very soon.) A couple of months later, though, Kendrick got a bigger award, when Damn was given the Pulitzer Prize for Music. The Pulitzer had never gone to a work of popular music before that; it was rare for a jazz artist to even win. It hasn’t gone to another work of popular music since then, either. In this way, as in so many others, Kendrick Lamar is one of one.

After Damn, Kendrick didn’t need to do features on pop records anymore. Kendrick might make a guest appearance on another rapper’s song if he really respected him, though. In 2018, Kendrick teamed up with Lil Wayne on the story-song album track “Mona Lisa,” which peaked at #2, though it reportedly was recorded many years earlier. (It’s an 8.)

Kendrick’s next project wasn’t a proper album. Instead, Disney pulled the unconventional move of recruiting Kendrick to serve as curator and executive producer of its Black Panther soundtrack. Most of the songs from that album aren’t in the actual movie, but Black Panther was a cultural phenomenon, the biggest movie of its year, and Kendrick was positioned as a big part of that triumph. Kendrick appeared on every track from that album, sometimes just doing uncredited backup vocals. The two big singles were Kendrick collaborations: the end-credits song “All The Stars,” with his TDE labelmate SZA, and the relatively sleek and clubby “Pray For Me,” with the Weeknd. Both of them peaked at #7. (“All The Stars” is a 6, and “Pray For Me” is an 8. SZA will eventually appear in this column. The Weeknd has been here before and will be back again.)

[embedded content]

After Damn and the Black Panther album, Kendrick Lamar went on a couple of big tours, became a father, and went silent for a long stretch of time. Even his guest-verses became increasingly rare. When Kendrick’s little cousin Baby Keem got him to rap on the 2021 single “Family Ties” and to shoot a video, that felt like an event. (“Family Ties” peaked at #18. Good song!) Kendrick’s next proper album didn’t come out until five years after Damn, and that album was way headier and more internal than what much of Kendrick’s audience wanted from him. 2022’s Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers made a big splash simply by existing, but it didn’t take over the world the way that Damn did. Four tracks from Mr. Morale made the top 10; “N95,” the highest-charting of them, peaked at #3. (It’s an 8.)

[embedded content]

When Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers came out two and a half years ago, Kendrick Lamar seemed like he no longer had much interest in pop stardom. Instead, he was in the esoteric zone. He’d already reached the point where he’d be famous and beloved forever, but his popular peak seemed to be over. That didn’t last. Someone said something that Kendrick didn’t like, and that activated the demon within him. Kendrick reacted like he was hearing the “Humble” piano for the first time. That version of Kendrick, the vengeful Kendrick, is the one that the world loves best. As it turned out, “Humble” did not represent the peak of Kendrick Lamar’s career. That peak is happening right now. We’ll see Kendrick in this column again, hopefully many more times.

GRADE: 10/10