Loretta Lynn could write. It takes a rare and difficult-to-quantify set of skills to write a great country song. You need to be able to tell a rich, emotionally resonant story — maybe saccharine, maybe not — in as few words as possible. Those words need to make musical sense, and they need to be written for someone who can inhabit those words. Nashville supports an entire industry of people whose job it is to crank out country songs, and the writers often aren’t the ones singing the songs. That industry has existed for nearly a century, and in that time, there haven’t been many writers sharper than Loretta Lynn.

Loretta Lynn didn’t have a typical songwriting background. She was born into deep poverty in Butcher Holler, Kentucky. Her father, a coal miner, died of black lung, and she married her husband Oliver when she was 15. Lynn followed Oliver off to rural Washington to raise their kids while he worked as a logger. Some of their children lived, and some did not. Sometimes Oliver cheated, and sometimes he didn’t. They stayed together. Eventually, Lynn bought a guitar, taught herself to play, and started singing in local bars. She wrote her debut single “I’m A Honky Tonk Girl,” released it on a small start-up label when a local businessman was impressed, and scored an unlikely national hit. That led her to Nashville and to stardom. Loretta Lynn was famous for a lot of things — her thick regional accent, her take-no-shit attitude, her string of hit singles about hot-button cultural issues — but her songwriting was the reason that anyone knows who she was.

When Loretto Lynn got famous, it wasn’t all that common for country singers to write their own songs, and Lynn sang plenty of great ones that she didn’t write. But many of her most immortal hits — “Fist City,” “Rated X,” “You’re Lookin’ At Country,” “You Ain’t Woman Enough (To Take My Man),” “Dear Uncle Sam” — are hers alone. Lynn co-wrote “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ On Your Mind),” her first country chart-topper, and “The Pill,” her biggest pop crossover. Both songs showed ferocious levels of perspective — Lynn refusing sex from a drunk husband and then celebrating her own ability to experience the wonder of birth control. It’s a mistake to hear country songs as pure memoir, but Lynn drew on her own experiences whenever she wrote. Before Coal Miner’s Daughter was an Oscar-winning biopic, it was a Loretta Lynn song.

The rise of any star, no matter the level of talent, is a time-and-place thing. Loretta Lynn arrived into Nashville as country music was pushing in a sparkling pop direction, and she worked with Owen Bradley, the producer with some of the sharpest, glossiest instincts in history. Her hill-country accent and perspective clashed beautifully with the clean, streamlined feel of Bradley’s music. Her range and timing were tremendous, but she always sounded conversational, and she never seemed to be showing off. When she wrote about societal issues like divorce or Vietnam, she didn’t preach or argue. She just delivered one person’s perspective with grace and authority.

Jack White wasn’t born when Loretta Lynn wrote most of those songs. He was two years old when Lynn scored her last country chart-topper. For most of the time that White was alive, Loretta Lynn was a relic of a past Nashville age, one who drifted further and further from the country mainstream in the ’80s. Loretta Lynn’s big comeback moment seemed to be Honky Tonk Angels, the 1993 album that she recorded with fellow veterans Dolly Parton and Tammy Wynette. That album tapped into a powerful reserve of country nostalgia, and it went gold. But the three of them never made another record, and Wynette died in 1998.

The White Stripes loved Loretta Lynn. They dedicated their classic 2001 album White Blood Cells to her, and they covered “Rated X” at live shows. After she heard their cover, Loretta Lynn cooked chicken and dumplings for the White Stripes at her house in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. She liked the band, especially “Hotel Yorba.” A few weeks after they released Elephant, the White Stripes played at New York’s Hammerstein Ballroom, and they brought Lynn up to open for them. My brother was at that show, and he said that Jack White and Loretta Lynn did a lot of hokey onstage flirting, like a Hee Haw sketch or like the banter on “It’s True That We Love One Another.”

In 2004, Jack White was pretty much at the peak of his cool, and he could work with whoever he wanted. He’d produced White Stripes records, and he’d done the same for Michigan peers like the Von Bondies and Whirlwind Heat, but it was still a genuine surprise when the world learned that Jack White was producing a Loretta Lynn record. When Lynn opened that White Stripes show, she was sitting on a new batch of songs that she’d written, and she hadn’t released a solo studio album in a few years. Jack White offered his services as producer, mostly because he wanted to work with her in any capacity that he could. White told CMT, “I’d play tambourine on this record, if that’s it. I don’t care. I just want to be in the same room with her and to be able to work on this.”

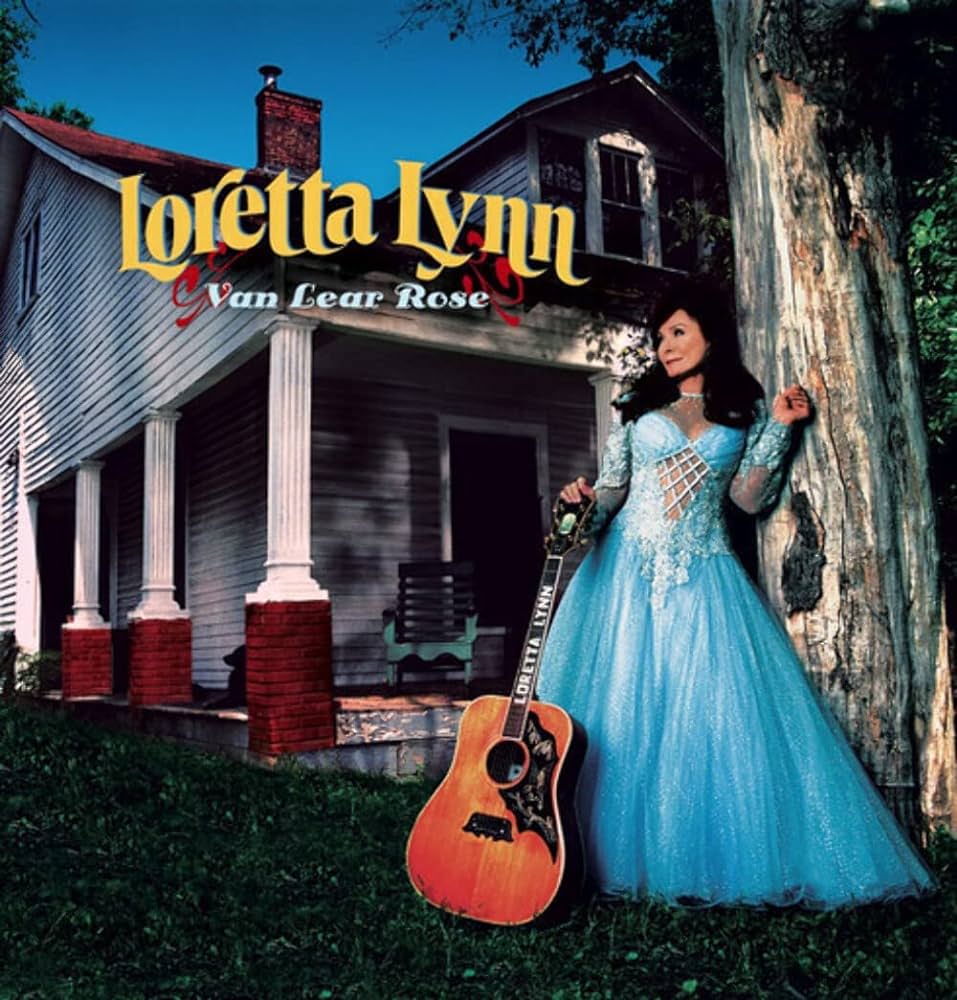

Loretta Lynn’s Jack White-produced album Van Lear Rose, which will turn 20 on Saturday, came out in a moment when the country legends of her generation were getting critical reappraisals and making prestige-heavy comeback records. Johnny Cash, who died in 2003, started the trend off, signing with Rick Rubin and making a series of albums with him that started in the mid-’90s. Dolly Parton did some bluegrass records and covered Collective Soul. Music critics rhapsodized about Merle Haggard’s hardscrabble life, while Haggard made some of the most stripped-down music of his career. In that context, the Loretta Lynn/Jack White connection made its own kind of sense.

At the time, Jack White’s involvement was the big selling point for Van Lear Rose. White played guitar on every track, sang the fiery one-night-stand duet “Portland, Oregon” with Lynn, and recruited the record’s backing band, pulling members from Cincinnati’s Greenhornes and Detroit’s Blanche. (The two Greenhornes guys, Patrick Keeler and Jack Lawrence, later joined White’s band the Raconteurs.) Van Lear Rose didn’t sound much like a White Stripes record, but it had some of the coiled, contained fury that those albums did. Sometimes, White and his collaborators went for a stripped-back version of old-school country grace. Sometimes, they indulged in full-on Zeppelin-style fireworks, which had nothing to do with the music that Lynn had spent her career making. Lynn seemed to relish the challenge, and she sounded like herself throughout. The music was different, but she wasn’t.

Listening to Van Lear Rose today, it’s fun to hear Jack White messing around with full-band arrangements, landing on early versions of the solo sound that he’d develop after the White Stripes broke up. It’s also fun to hear him go full-on rootsy country on a few songs; the White Stripes had only ever flirted with that stuff. But today, the real reason to revisit Van Lear Rose is that it’s a record full of Loretta Lynn songs. Lynn wrote every song on the album, and she’s the sole songwriter on most of them. With those songs, Lynn expressed some heavy things that must’ve been weighing on her, but she did it with the effortless econmy of a great country songwriter. You can hear the clearest expression of that gift on the heart-crushing “Miss Being Mrs.” It’s Lynn’s song about life as a widow after her husband’s 1996, death: “My reflection in the mirror, it’s such a hurtful sight/ Oh, I miss being Mrs. tonight.”

In many ways, Van Lear Rose feels like an end-of-life record. When the album came out, Loretta Lynn was 72, and Jack White was 28. On the album-opening title track, Lynn sings about the ways that her father described her mother. She spends most of the album remembering people who weren’t in her world anymore and her childhood back in Butcher Holler, describing the happiness of familial love rather than the depth of poverty: “Well we lay on our backs and we count the stars/ ‘Cause up here, folks, heaven’s not that far.”

Lynn also trots out her old persona, going back to the situations that animated so many of her songs. Old characters make returns, like the no-account husband who leaves his wife at home with the kids while he’s out raising hell: “Well, you told me you’d be happy bouncing babies on your knee/ While I sit at home alone, and I’ve been bouncing three.” And then there’s the woman who lures that husband away from home: “I brought along our little babies ’cause I wanted them to see the woman that’s burning down our family tree.” One of the only songs with a co-writer is “Trouble On The Line,” about a couple’s total failure to communicate with one another. Lynn wrote that one with Oliver, her late husband.

The other co-writer on the album is Jack White, who’s credited with the instrumental track of “Little Red Shoes.” That song isn’t really a song. It’s just Loretta Lynn telling stories about her childhood, with a shuffling twang behind her. I wonder if White just recorded her talking and then added the music. On that track, Lynn describes the poverty and bleakness of Butcher Holler in ways that never quite shine through on her regular lyrics. She tells of a time when she accidentally got bonked on the head as a little girl and knots started appearing on her head. Doctors thought that she would die, and the nearest hospital wouldn’t admit her “because Mommy and Daddy didn’t have no money. They just tell ’em to take me home and let me die, you know, ’cause there wasn’t nothing they could do about that kind of disease, I guess.” When baby Loretta seems like she’s about to leave earth, her mother steals a pair of red shoes for her. She laughs while she tells the story, as if it’s charming, and it is. It’s terribly sad, too.

Van Lear Rose isn’t a definitive Loretta Lynn album. If she’d never made it, her legacy would still be secure. Her classics are the records that she made with Owen Bradley, the ones that truly resonated in a culture that needed to hear them. Van Lear Rose is nowhere near as consistent as any Loretta Lynn best-of collection that you might buy from a truck-stop CD rack, but the great moments really are great, and they don’t sound like anything else that she ever did. Van Lear Rose also introduced Loretta Lynn to people like me, White Stripes fans who didn’t really grow up with classic country music. Once you heard what she did with Jack White, you could do your own digging.

The singles from Van Lear Rose didn’t make the country charts, and the LP never went gold, though it did win a Grammy for Best Country Album. Critics loved it. On that year’s Pazz & Jop Critics Poll, Van Lear Rose came in at #3, ahead of Franz Ferdinand’s debut and behind Kanye West’s The College Dropout and Brian Wilson’s reconstructed version of Smile. Look at that top four — nothing but debuts and rediscoveries. Critics love ingenues and legends. Don’t try to tell us about a band making album number five; we don’t want to hear it. We’re like direct deposit — only showing you any love on the first and fifteenth.

As it turned out, Van Lear Rose was not an end-of-life album. Loretta Lynn lived for another 18 years, making a few more albums before leaving us at the age of 90. I’m sure she enjoyed the attention that the album brought, but she had more things to do with her life. In her titanic career, Van Lear Rose isn’t exactly a footnote, but it’s a lark, an exception. Today, for whatever reason, Van Lear Rose isn’t on streaming services. That sucks, but it’s not the end of the world. You can find Van Lear Rose if you need it. And if you’re looking for evidence that Loretta Lynn was an all-time great songwriter, you won’t have to look too hard.