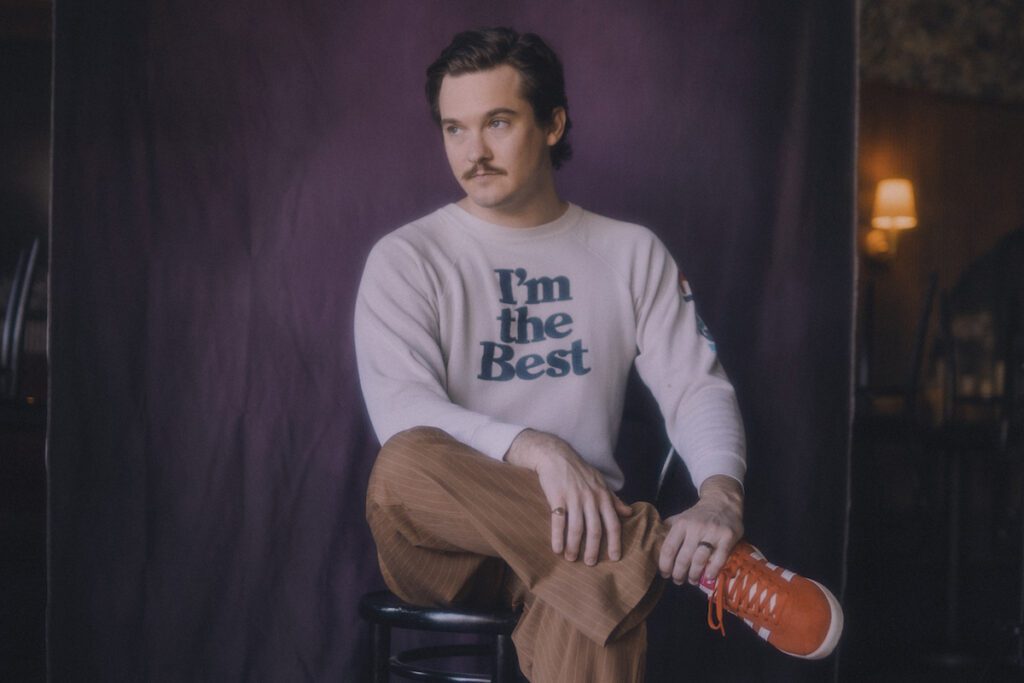

“My band is Chris Farren and my name is Chris Farren.” – Chris Farren

It sounds so casual when he lets it slip during our Zoom conversation, but Chris Farren has hit upon the exact reason that he had gotten so utterly sick of Chris Farren. While the power-pop neurotic – a guy obsessing over obscurities and micromanaging melodies as a hedge against the unpredictability of human interaction – has been an enduring archetype over the past half century, they usually have a bassist or sound tech or even a manager that they can rely on to keep their nagging self-doubt in check. But not only is Chris Farren the frontman of the band Chris Farren, he’s the only member. During what should have otherwise been a triumphant tour behind his 2019 album Born Hot, “At the end of every show, these fun shows, I would be in the green room alone being like, Good job, Chris!” he jokes. “I want someone to high five, like…We did it!”

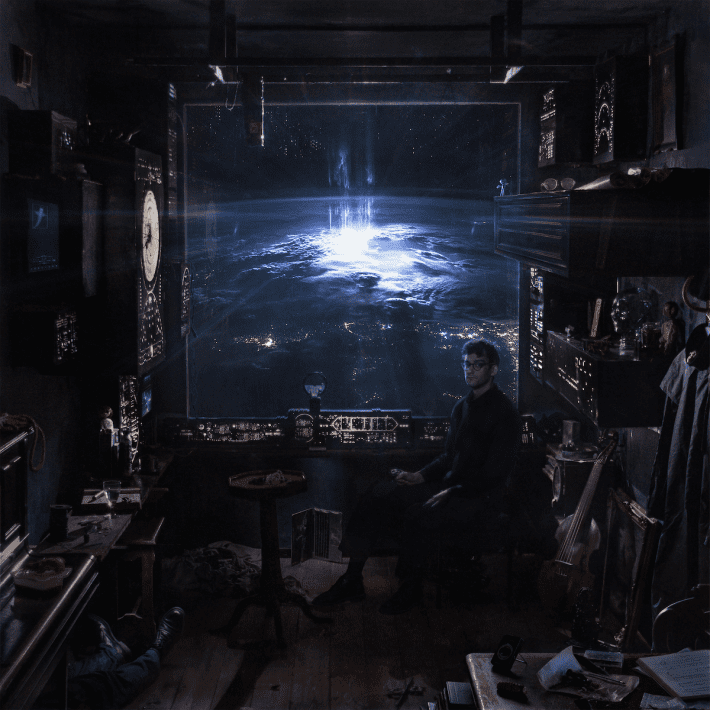

Again, Born Hot was released in 2019, so Farren’s desire for community has grown understandably more urgent in the time since. Regardless of whether Doom Singer is Farren’s strongest or most ambitious solo album yet (it is both), it’s his most collaborative and the willingness to relinquish total control has resulted in it being the first that didn’t leave him feeling completely miserable when it was finished.

This is largely due to “Chris Farren” actually sounding like a real band, and not one guy trying to reimagine the past five decades of power-pop in his closet. Most of the time, the difference is as simple as “there are real drums this time” – advance singles “Bluish” and “Cosmic Leash” have a familiar charm, but they’re dynamic and expansive in a way that can’t be replicated by playing over a ticky-tack backing track. The Beatlemania of the title track itself is not a new look for Farren, yet its careful structure and texture suggest it was knocked out Get Back-style, by a couple of people jamming in a room until something clicked.

For all of the ways Farren challenged himself as a writer and a bandleader, the initial creative process remained mostly the same: “I literally write 80-100 songs for every record, which sounds impressive, but they are awful songs,” he shrugs. “Except for the 12 songs I polished enough to hand to somebody else.” But in this instance, he had a writing partner in Frankie Impastato, drummer of the rejuvenated emo favorites Macseal and the first non-Farren touring member of Chris Farren, the band. And whereas previous albums would be painstakingly tweaked in Farren’s makeshift closet/studio, Doom Singer was produced by his Polyvinyl labelmate Melina Duterte, aka Jay Som.

Duterte isn’t quite a peer of Farren; she was 15 when Fake Problems released their SideOneDummy debut It’s Great To Be Alive in 2009. Still, Farren considers her to be something of a role model in terms of balancing low-key, collaborative endeavors with a main gig that runs the risk of obliterating the boundaries between public and private persona. While Jay Som was swept up in the Bandcamp-to-bandshell wave of the mid-2010s that turned Mitski, Soccer Mommy, Alex G, Phoebe Bridgers and many, many other quasi-solo acts into festival-topping, indie A-listers, the project has largely been put on hold since 2019’s Anak Ko. In the time since, she’s become an essential contributor to boygenius both live and in the studio, started Bachelor with Palehound’s El Kempner, and served as a producer for artists like Whitmer Thomas and Living Hour. “With the Jay Som stuff, I think she was a little burnt out on touring, which I literally have never been,” he says, as his facial expression adds sarcastic square quotes. “I love this stuff.”

Farren’s vision for a more sustainable and diversified creative existence is a massive shift from the relentless grindset that defined the Fest-centered milieu from which he emerged, as a member of erstwhile Florida pop-punkers Fake Problems, the Jeff Rosenstock collaboration Antarctigo Vespucci, and as a solo act, beginning with Can’t Die in 2016. Can’t Die was buoyed by the success of Rosenstock’s WORRY. and PUP’s The Dream Is Over in the same year, modern classics that created a bridge between more mainstream indie audiences and those who had been long familiar with the type of artist that had been bubbling up within the SideOneDummy extended universe throughout the 2010s – kinda pop-punk, a little Warped Tour-curious, always anthemic, and defined above all else by a self-deprecating sense of humor about their masochistic touring regimen. The promo cycles for those albums are still spoken of in hushed tones, whether it’s the WORRY.-brand condoms or, a year later, Rozwell Kid pitching their album with a mailed potato.

Both sonically and spiritually, Can’t Die fit into that mold, but Farren’s homebody nature cut against the road dog reputation of his labelmates; if “Chris Farren” were more a band in the “Death Rosenstock” format, perhaps he would’ve been more inclined to bust his ass touring in whatever venue might have him. Earlier this year, PUP and Rosenstock played a literal arena rock show with Joyce Manor, a realization of what Farren once imagined for himself in Fake Problems. “From 20-27, I would constantly be like, and now, I’m gonna be famous,” he admits.

To this point, his closest brush with actual fame came in 2014, when he created a parody the Smiths T-shirt – a mashup of the legendary band’s typeface with a picture of the Hollywood Smith family – that ended up being presented to Will Smith on Late Night With Jimmy Fallon. To this day, Farren’s music has often been overshadowed by his broader reputation as a Guy Who Does Funny Stuff; witness the billboard erected in Los Angeles to promote the Born Hot-line, or the viral sensation of a 22-oz. stadium cup he made to accompany the release of Death Won’t Wait, an “original soundtrack” for an action movie that doesn’t actually exist. (Spin interviews: Death Won’t Wait cup 1, Chris Farren 0.) Or, really, just look at any video he’s ever made. “I don’t think people see this except for those who really know me, but all of my videos and stuff, I look at them and think, this person is so full of hatred and contempt for this whole process, and I’m saying these things in these weird exaggerated ways that it doesn’t come across,” he explains.

True enough, even if Doom Singer’s title is largely truth in advertising. While there are nods to any number of obvious, encroaching harbingers of political, societal or environmental catastrophes littered throughout Farren’s chipper pop-rock, he’s not trying to make OK Computer. His subject matter is the kind to be expected from a 37-year-old married man trying to carve out a livable creative existence in Los Angeles: Social media has made his career infinitely easier at the cost of his mental serenity. Presenting as a nice guy in public while feeling like a jerk in private. Evolving beyond the 20-something version of himself that was more of a jerk in public.

But making hilarious multimedia content to mask his ambivalence toward clout-chasing behavior aligns with Doom Singer’s entire songwriting philosophy, what Farren has called his “sweet spot” – the classic contrast of massive, major-key hooks with equally massive self-loathing. The press materials for Doom Singer describe this emotional pitch as “optimistic nihilism,” but for all of Farren’s discomfort with self-promotion, no one could possibly do a better job of summing up the Chris Farren M.O.: “I genuinely love doing this stuff…but I have to think of ways to promote this that don’t make me want to fucking die.”