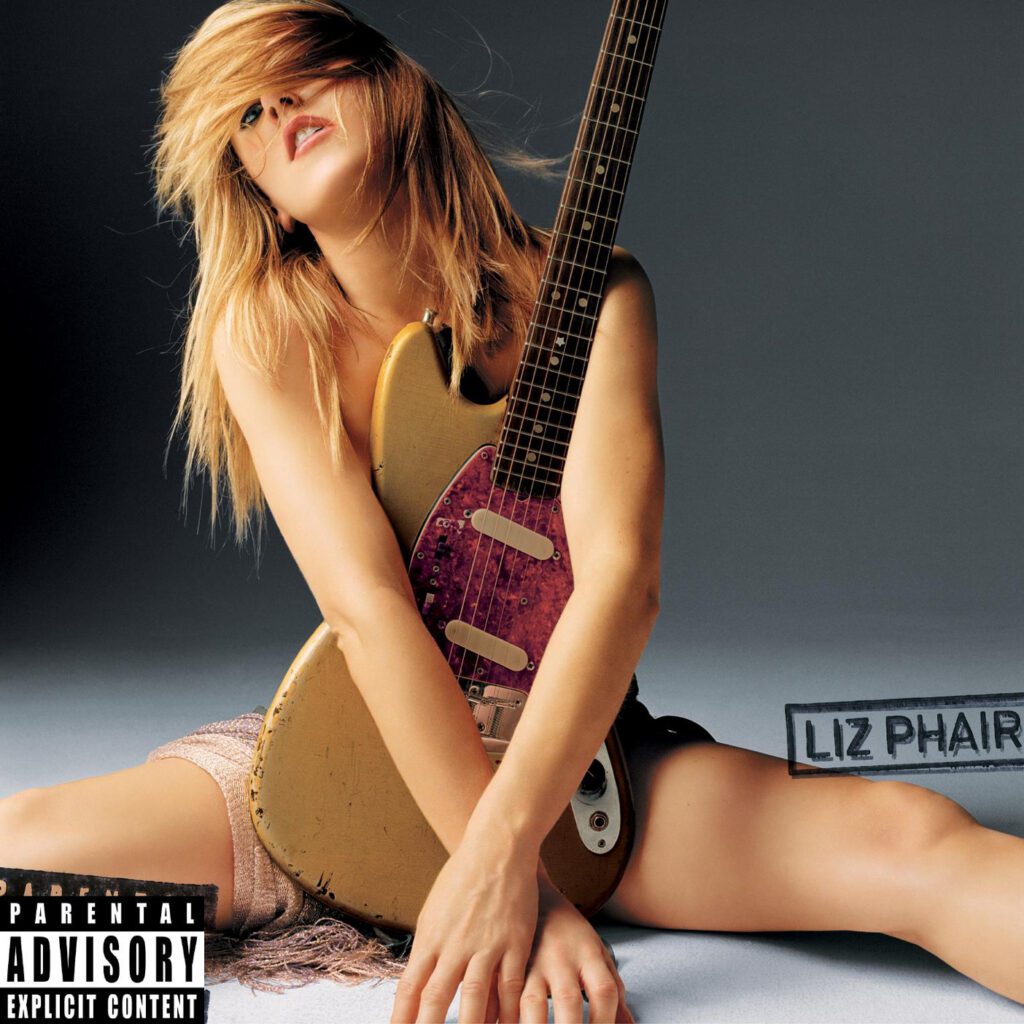

When Liz Phair released her 2003 self-titled album 20 years ago this Saturday, many people viewed it as a Shakespearean betrayal of her indie roots. A decade removed from her lo-fi rock opus Exile In Guyville, Phair had gone to the dark side — the Top 40 — and was collaborating with slick writing and production team the Matrix, who were fresh off hits with Jason Mraz and Avril Lavigne. Led by the sugary ode to desire “Why Can’t I?” and soaring rocker “Extraordinary,” Liz Phair was unapologetically pop-leaning.

“I needed to be able to do things that were challenging to me,” she told me in 2003, for a feature in the now-defunct magazine Women Who Rock. “We obviously sought out the Matrix so that we could try to get a song that could be played on the radio, but the process of working with them was just as rewarding as writing a song on my own. It allowed me to vocalize feelings in a grandiose formula that thrilled me. It’s very exciting for me.”

On an airplay level, Liz Phair certainly introduced her to entirely new audiences: “Why Can’t I?” became her first and only US Top 40 single, peaking at #32, and was a top 10 hit at adult contemporary radio. (Appropriately, it also ended up being heard in romantic comedies like How To Deal, Win A Date With Tad Hamilton!, and 13 Going On 30.) “Extraordinary” similarly became an adult contemporary hit.

Despite this success, neither song is standard pop fare. “Why Can’t I?” is all about the irresistible pull of lust and longing, with lyrics that hint at illicit dalliances (“Got a girlfriend, you say it isn’t right/ And I’ve got someone waiting too”) and boldly state future intentions: “Here we go we’re at the beginning/ We haven’t fucked yet, but my head’s spinning.”

“Extraordinary,” meanwhile, is a subtle critique of men who expect women to be superhuman (“So I still take the trash out/ Does that make me too normal for you?”) or bend over backwards to impress him. She’s not impressed: “What exactly do you do?/ Have you ever thought it’s you that’s boring?”

These nuances were often lost on critics. Some reviews of Liz Phair were positive: Entertainment Weekly called it “an honestly fun summer disc with plenty of dark crevices” and Blender astutely understood the music’s intentions. In contrast, many other reviews ripped the album to shreds while lobbing personal insults at Phair.

Beneath the headline “Liz Phair’s Exile in Avril-ville,” The New York Times dubbed the album “an embarrassing form of career suicide” and sneered, “You half expect the ‘i’s’ in her liner notes to be dotted with little hearts.” The Guardian huffed, “Where she used to be smart and provocative, Phair has become crass and bloated, her lyrics crude and her image apparently a grotesque exercise in self-parody.” And the album earned an infamous 0.0 score from Pitchfork, with the review noting, “It’s sad that an artist as groundbreaking as Phair would be reduced to cheap publicity stunts and hyper-commercialized teen-pop.”

These reviews emerged during a time when pop music wasn’t taken as seriously as it is now, which no doubt explains some of the skepticism toward Phair’s move to polished production and big choruses. (And in the case of the Pitchfork review, writer Matt LeMay apologized years later.) But the cheap shots at Phair’s outfits, lyrics and approach scan as scolding and puritanical — insinuating that a woman can’t be both smart and sexual — and drip with ageism. How dare Phair be expressing desire when she was 36, a mom, and newly divorced!

Women in music are unfortunately no strangers to misogyny, of course. Even still, speaking to the Austin-American Statesman in 2003, Phair admitted that she was surprised at what the interviewer termed the “often venomous reaction” to the album. “I figured some people wouldn’t dig it, because if you’re an old indie rock fan, it’s not your thing. But people really, really, really took it personally. It’s like I’m a politician who campaigned with Guyville, but now I’ve changed my platform.”

With two decades of hindsight, it’s clear how unfair the vitriol was to Liz Phair — both the album and the artist. Liz Phair doesn’t sound like a gigantic curveball or some morally bankrupt pop sellout, but a logical (if more commercially driven) next step after her 1998 album whitechocolatespaceegg. The difference in reception to the two albums came down to context: The latter was marketed as an alternative release, and the former was geared toward the pop world.

“It’s my choice to chart uncharted territory for myself,” she told me. “I don’t want to be — and this is how I felt in the industry as it is right now, cause it’s so hit-driven — I don’t want to be sidelined into oblivion. I want to be an artist that’s making a statement for womankind that matters, and gets heard.”

Revisiting Liz Phair today, it’s striking how much influence the music takes from ’70s rock and power-pop. Chalk that up to her fondness for these genres and her collaborators: In addition to the Matrix, Phair worked closely with songwriter Michael Penn, who produced five songs, including the highlight “It’s Sweet,” a simmering psychedelic-kissed rocker with ecstatic lyrics about falling in love. Elsewhere, Wendy Melvoin adds bass to the lighter-flicking power ballad “Friend Of Mine” and guitar to the surging pop-rocker “Take A Look.” Phair also produced songs herself: “Love/Hate,” a keyboard-dazzled power-pop anthem calibrated for arenas, and the spaced-out, indie-leaning “Firewalker.”

Perhaps best of all is the mighty anthem “Rock Me,” a slab of glossy glam-pop with windmilling power chords and a cascading chorus. The latter song also features the album’s best lyric: The protagonist, who is dating a younger man, quips, “Your record collection don’t exist/ You don’t even know who Liz Phair is.” It’s savvy commentary on ephemeral pop culture, Phair’s own supposed fame, and the absurdity of generational differences. But it’s also a very funny and self-deprecating line — a tone that’s often overlooked within Phair’s music.

This tone is difficult to pull off, and Liz Phair does stumble in spots — namely with the Matrix collaboration “Favorite,” a flop that posits that a man is “like my favorite underwear/ It just feels right, you know it.” But Phair’s more serious moments resonate. “Little Digger” is a heart-stopping song in which Phair hopes that her then-recent divorce hasn’t affected her then-young son: “I’ve done the damage/ The damage is done /I pray to God /That I’m the damaged one.” And the protagonist of “Bionic Eyes” — a boogie-rocker featuring guitar from Buddy Judge, who was in ’90s cult act the Grays and also served as Phair’s musical director — is absolutely over boring men: “I watch the years go by/ These are the same old guys/ I never had any use for/ Beyond the feeling of pleasure/ Or the thrill of the fight.”

And then there’s “H.W.C.” (an acronym for “hot white cum”), a liberating song starring a protagonist who enjoys having sex and won’t apologize for embracing this pleasure. “Part of why I put that on was a reaction to a lot of record executives, because they kept hearing that song – it’s a pretty old song – and they’d be like, Great song! Could you change the lyrics? Maybe make it ‘Hot White Love’?” she told The A.V. Club in 2003. “I’d be like, ‘Okay, it’s not going to make the record.’ And I’d just put it away and not care about it.”

Eventually, she came around to the song in its original form, in part because of what it represents. “I’d be sitting there thinking, like, ‘They really like the song, yet I can’t put it on because it offends their masculinity or something, or it’s too freaky, or too wild?’ And I thought, ‘If I can’t be wild, if I can’t put a song like that on my record, then I’m kind of blowing my own aims for what art is supposed to be, which is a place to be free.’”

It’s hard not to think that Liz Phair would have been celebrated, not villainized, had it been released in 2023. For starters, the record feels like a massive influence on modern music: You can hear elements of Phair’s sweet-and-sour pop in countless bands (to name a few, Speedy Ortiz, Snail Mail, Soccer Mommy), while “Why Can’t I?” has been covered by Nashville songwriting group the Song Suffragettes. The Dismemberment Plan’s Travis Morrison even once astutely pointed out to Slate the longer-tail legacy of Liz Phair: “Now hipsters listen to Carly Rae Jepsen and no one thinks about it. But Liz Phair was pretty ahead of that curve.”

Alongside redeemed pop albums such as Christina Aguilera’s Bionic and Lady Gaga’s Artpop, Liz Phair is finally ready to be analyzed and embraced on its own terms.

“Part of getting divorced and all this kind of stuff that I’ve been through, and my age, and having a son, is you have to kind of come to terms with you, your whole self,” she told me in 2003. “I had to kind of integrate everybody that I had been — the dumb, syrupy suburbanite, the tomboy athletic girl. I had to kind of bring everybody all up into who I am right now — it’s obviously a work in progress.”