On Valentine’s Day 1995, Tupac Amaru Shakur became Inmate No. 95A1140: 5’11”, 145 pounds, pacing his cell, chain-smoking Newports, devouring dozens of magazines and newspapers and writing furiously in his notebook. He was a man possessed by boundless energy, a person defined by his Faustian hunger for more than mere existence, one who clearly knew he had so little time in this world. Yet here he was: shackled in the chains of Clinton Correctional Facility in upstate New York. His status as a folk hero, more cause célèbre than celebrity, meant his movements were limited by involuntary protective custody status. So he sat, stewed, barked, raged and grew angrier.

Not yet 24-years-old, Tupac was already a multi-faceted star. He had a pair of gold records, supporting or co-starring roles in four movies that were hits in urban markets, and had begun to be recognized — for better or worse — as the voice of young black men in America. People knew he was working towards something great — perhaps even historical — yet his budding superstardom had yet to enter full blossom. This was a man on the ascent, a supremely multi-talented, multi-medium artist with the magnetic charisma of Alexander the Great or Shaka Zulu, and his rise from teenage obscurity to rap’s biggest star was as tumultuous and infamous as it was meteoric.

The term Tupac began serving in February 1995 was a one-and-a-half to four-year sentence for a conviction of first-degree sexual abuse stemming from a November 1993 incident where he and his road manager, Charles Fuller, groped a woman in his room at the Parker Meridien Hotel in Manhattan. In the middle of this high-profile, high-stakes trial, Tupac, of course, found time to record.

On the night of Nov. 30, 1994, while waiting in the lobby of Quad Recording Studios in Times Square for a session with Puff Daddy and Notorious B.I.G., though, things changed: Tupac was shot five times and robbed. He showed up for the jury’s verdict two days later in a wheelchair and freshly bloodied bandages.

Despite the heinousness of his crimes, it’s easy to understand how and why the rap press and rap listeners avoided processing them at the time. Tupac was at war with the entirety of the world around him. Since 1991, he successfully sued Oakland P.D. for police brutality, shot an off-duty cop in Atlanta, been convicted of or tried for numerous weapons and assault charges, was publicly condemned by the vice president of the United States, and seemed to piss off most of white America at least once a month.

Tupac appeared to be a magnet for high drama, if not high crimes and misdemeanors. What’s remarkable is despite this swirling crescendo of noise and chaos surrounding him, he never lost focus on his craft. Great rappers are studio addicts: people who, for whatever reason, cannot stop making music. It makes sense that at this point, surrounded by headlines, stuck in a prison cell with only cigarettes, a tiny radio, books and his pen for comfort, that Tupac was itching to get back into the booth.

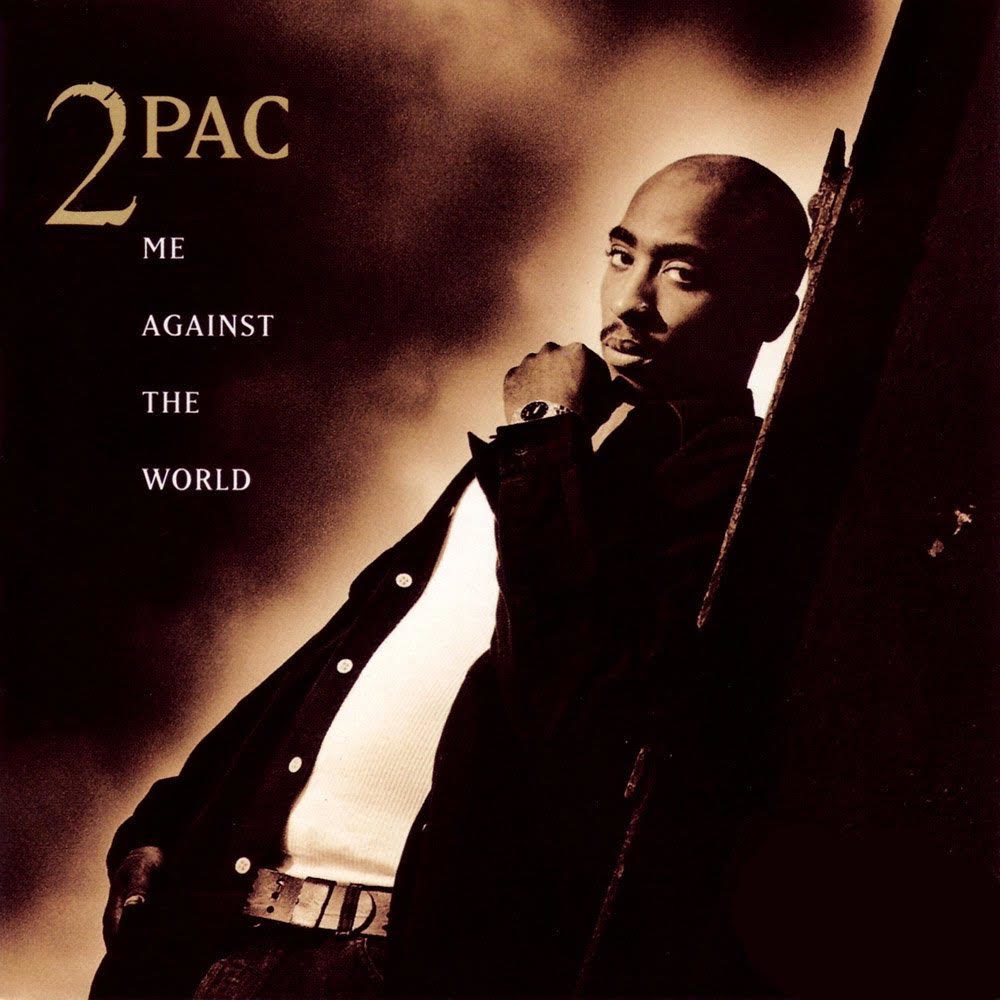

Through however many legal battles and public controversies he faced the previous year, Tupac had been honing his sound, finding something that split the difference between the more abrasive gangsta rap records of the ‘80s, the syrupy G-funk of the early ‘90s, ‘70s soul and the R&B charts. Thug Life: Vol. 1, which Tupac recorded in 1994 with the hastily assembled (and just as quickly disbanded) group Thug Life, was when he happened into the formulation which was best attuned to delivering the street parables his pen had been delivering the whole time. It wasn’t quite the breezy, alt-rap inspired production of 2pacalypse Now, a sound that was more reflective with the artist’s more cherubic teenage spirit, nor was it the bouncy, clubby, and bass-driven tunes of Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z. It was world-wearier, more gospel than club, more harps and piano than synthesizer and vocoder, chord progressions which trended towards abjection rather than ascension. It is a subtle difference, but just as important as legal drama and lyricism in Tupac reaching his final form.

Splitting time between studios in Los Angeles and New York, between court dates and dates with Madonna, between film shoots and fashion runways, Tupac found his voice; he finally made sense of the contradictions and controversies that defined him. The complex, and frankly magical, process that occurs when an immortal artist and pop icon reaches the creative zenith of their powers and submits their entry to the canon is impossible to quantify with statistical analysis, with graphs of internal rhyme structures and vocabulary value judgments, by tracking beats per minute and major scales.

2Pac the rapper and Tupac the man were separate entities. His brilliance was in simultaneously opening a window to his inner life and sublimating the shared experiences, stories, and attitudes of the black youth of his generation.

For 2Pac, it was never about all that bullshit. For all his technical skill, it was always about speaking from the soul and forever feelings over facts. Me Against the World’s opening track, “If I Die 2nite,” is beyond technical, an impossibly precise alliterative assault of poetically percussive p-sounds. It’s a rap track so perfectly written and masterfully delivered that the beat slinks between the trumpet-like flow and becomes a footnote. Still, what you remember is not that display of skill, but how his voice pulls from the bottom of his chest, breathing in between bars and welling upwards with anguish at every annunciation and inflection. It is a vocal performance that peaks when 2Pac pleads with you not to shed a tear for his death because he’s not happy on Earth, and imagines the headlines that will accompany his burial. The 66-minute album has not even reached the 300-second mark.

There’s more than a dozen more moments like that on the record, where 2Pac spits from the bottom of his soul and into the center of your field of vision. On “Lord Knows,” he captures that hourly cycle of self-inflicted wounds that defines the inner life of addicts. On “Fuck The World,” he manages to fit his rape conviction into a larger narrative of black men victimized by the prison industrial complex without sounding ridiculous. Between so much crushing despair, there’s “Old School,” an account of his adolescence in 1980s New York City that establishes a shared series of reference points with the audience he was always speaking directly to, pays homage to the greats before him, and establishes an intertextual relationship between his career-defining project and the genre’s canonized classics.

Chief among these moments was “Dear Mama,” a song that is probably as important to understanding Tupac as it is to understanding sons and mothers in America at the end of history. It is a tribute to Afeni Shakur, the entire woman: the Black Panther, the drug addict and the revolutionary, the prisoner and the mother. On top of a soulful guitar lick and handful of keyboard keys, 2Pac poured his soul out of his chest, telling the story of a woman who fought every day to provide her children with dignity and spiritual sustenance no matter the odds stacked against them. The brutal honesty of his narrative made “Dear Mama” a cultural touchstone and speaks to the bonds people form through adversity and illustrates all of the beauty in imperfection.

On the strength of these songs of pain, perseverance, righteous fury, desperation,, suicidal ideation, and triumph, Me Against the World was the first 2Pac album to debut at number one, staying on top for four straight weeks. The blistering emotional honesty, the ability to put so much of himself into every single syllable, was so gripping, so undeniable that the album did not require a conventional club record, nor a single compromise in 2Pac’s vision. And as important as 2Pac’s force of personality was, he often abandons 2Pac, the character, to create vignettes of young black men navigating poverty, racist courts, militarized police, gang violence and despair. So much of Me Against The World’s best writing occurs when Pac describes the psychological scars felt in the collective unconscious. The third verse of “Heavy in the Game” begins with a crushingly blunt couplet: “I’m just a young black male, cursed since my birth/ Had to turn to crack sales, if worse come to worse.” Just two bars encapsulating all the despair, nihilism, and defiance of a generation terrorized by Reaganomics and the Crack Epidemic.

“Death Around the Corner” is a psychological thriller that brings you to the depths of fear, to that room, pacing, constantly looking out of the window, clammy hands clasped around the trigger of an assault rifle, haunted by the screams of dying friends, too paranoid to trust those friends still alive, resigned to an early death yet living in constant terror of when it will come; these three verses are as haunting, as viscerally real as any artistic portrayal of PTSD and paranoia, no matter the medium.

Four days before the album dropped, Tupac filed a request for Interview or Information to the New York Department of Corrections, detailing his conditions at Clinton. He was under 24 hour a day lockdown, without bedsheets, begging for a transfer to a different prison or reclassification from his Involuntary Protective Custody Status. He spent another six months bickering with officials, pacing, chain-smoking, cut off from the outside world, with only books, a radio, and an occasional visit from his wife, Keisha Morris, (whom he married while incarcerated) for solace. Less than 11 months after his October 1995 release he was murdered.

Though it was not the last album Pac released, Me Against The World is arguably his most accomplished and important. By capturing just how suffocated he felt at every level of American life he created a damning indictment of the country that hated him back. It was when he found the sound and voice that we remember him for, when he transformed gangsta rap into a vehicle for the blues, and when he ascended to cultural omnipresence. Two-and a-half decades later, he’s yet to touch down.