In a 1905 essay titled “Street Music,” Virginia Woolf mused on how oppressive societal norms suffocate the human need for self-expression and deprive us of life’s natural rhythms. In railing against the common disdain for street musicians, she wrote, “We have trained ourselves to such perfection of civilisation that expression of any kind has something almost indecent — certainly irreticent — about it.” Though Woolf was referring to early 20th century English society — characterized by archaic gender roles, farcical etiquette, and an unending list of taboos — it’s striking how much this quote still rings true. In 2024, despite undeniable social progress, the sanitized vacuousness of society is still palpable, with each of our precious lives sacrificed at the altars of convenience and profit, and our popular “art” congealed into one focus-grouped, corporate-friendly, self-degradingly palatable ooze.

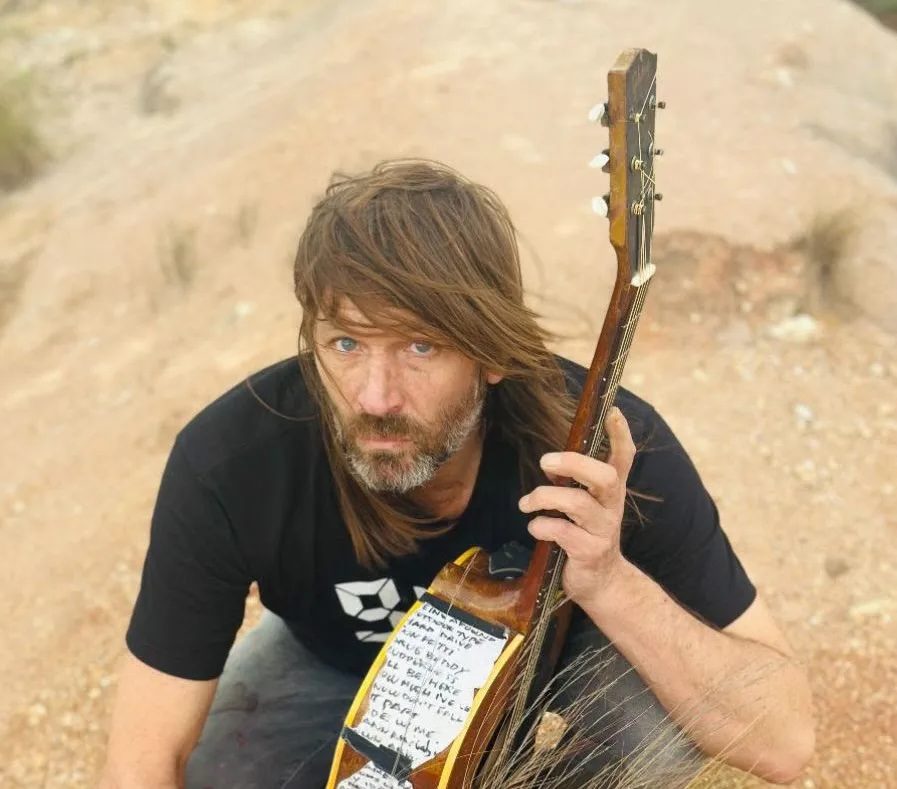

On several occasions, Damon McMahon, the acclaimed avant-garde-turned-pop singer-songwriter behind Amen Dunes, has described Woolf as his favorite writer — at times, even incorporating excerpts from her works into his lyrics, like 2011’s “Swim Up Behind Me,” which pilfers lines from Jacob’s Room. Though few writers could fully be compared to Woolf and her revolutionary, deeply psychological stream of consciousness, McMahon’s complex, abstract character studies bare at least some resemblance. And in keeping with Woolf’s sentiments about societal repression, McMahon’s forthcoming sixth album Death Jokes wrestles with a similar contemporary void, marked by a nefarious lust for vanity and competition and an absence of perspective on how to meaningfully live and die.

Death Jokes is the first Amen Dunes album in six years, so for many listeners, the stakes feel heightened. Then, add the pressure of measuring up to the career-defining artistic triumph and widespread praise of this LP’s predecessor: 2018’s Freedom. Freedom is the type of record most artists will never release — swaggeringly haunting, uniquely otherworldly, and exquisitely imperfect — and it undoubtedly brought McMahon more mainstream notoriety, from a coast-to-coast US theater tour opening for Fleet Foxes and a record deal with the revered Sub Pop to a songwriting gig for Liam Gallagher (one of McMahon’s heroes).

Such developments would’ve seemed far-fetched back in 2004, when his buzzy stoner art-rock band Inouk split up after one album, or in 2006, when McMahon’s solo debut Mansions (the only record released under his own name) received negative-to-mixed reviews, or in 2009, when Amen Dunes’ first LP DIA shirked accessible sounds in favor of chillingly atonal tape recordings and, in his words, “angry” experimental drone. But at the dawn of the following decade, with Amen Dunes’ next two records, 2011’s dark avant-pop Through Donkey Jaw and 2014’s hypnagogic, acoustic Love, McMahon finally figured out how to marry his offbeat experimentalism and budding pop ambitions.

While some understandably christened McMahon a psych-folk savior, with each release, it’s become increasingly clear that no genre descriptor can effectively encapsulate his free-wheeling sonic mystique. After all, how many American rock critical darlings have released a collection of Ethiopian pop renditions (2012’s Ethio Covers), or an oft-forgotten album of strident “non-music” recordings inspired by avant-garde composers like Julius Eastman and Robert Ashley (2013’s Spoiler)? And funnily enough, Freedom, which pulls from a familiar palette and features some of his most accessible work, sounds almost as elusive as his left-field dirges. It’s a bit like Lee Mavers doing his best Bob Dylan-meets-hip-hop impression, a spookier, more artful War On Drugs, or a higher-fidelity, more electronic Weak Signal, but above all, it’s painfully and euphorically human — like there’s a lot at stake emotionally. Upon release, Freedom’s melodies and vocal performances were the most transcendent of McMahon’s career, with each note beaming with instinctual rhythm and with every word crackling from inside him like a scraggly rock ‘n’ roll raconteur, an enlightened reggae singer, and a geriatric automobile engine.

Death Jokes is also hard to put your finger on. Vibrating with audacious, UK garage-inspired programmed drums, daringly contorted loops, and evocative samples from stand-up comedy, raves, protests, a copy machine, and almost anything else you can imagine, these songs are entire worlds unto themselves. Some sound like maximalist rave-rock anthems (“Joyrider,” “Rugby Child”), others askew electronic-folk ballads (“What I Want,” “Exodus”) or madcap musique concrète ramblings (“Boys,” “Round The World”). It’s by far the most lush Amen Dunes album yet — what you hear on your first listen will differ from your second, third, fourth, and so on.

The laid-back spaciousness of Freedom is absent, and if there are any ghosts from the past, it’s the eerie robustness of DIA, or even the zestful idea explosions of Inouk’s No Danger. With layers upon layers of heady beats, bleary samples, and atmospheric keys, McMahon risks masking his greatest asset: those reedy vibrato vocals. At times, the overbearing percussion of “Rugby Child” crowds McMahon’s ethereal intones, and the jarring production on “Boys” distracts from his swirling multi-tracked quavers. But elsewhere, the folky, Westerman-esque “Purple Land” (the British singer-songwriter contributed vocals to an Amen Dunes remix of “L.A.” back in 2019) and the misty, Dire Straits-like “I Don’t Mind” are perfectly balanced, with McMahon’s vocals magnetizingly foregrounded on the former and tastefully weaved into the cacophony of the latter.

The lesser emphasis on guitars is also glaring, as Death Jokes centers on immersive percussion, boastfully booming like a classic hip-hop LP and intermittently skittering and thwacking like forgotten loose change clanging around inside a dryer. The beats on interludes like “Joyrider” and “Predator” are deliciously brash, and the percussion on wispy, more rock-forward tracks like “Exodus” and “I Don’t Mind” has a spine-tingling tactility. Similarly, the album’s samples are deployed quite percussively, calling to mind the rich, challenging sampledelia of DJ Shadow and cultivating a larger-than-life beauty and emotional weight.

While Death Jokes is peppered with intoxicating imagination and inspired grit throughout, it lacks the front-to-back transcendent ease of Freedom, in part due to tracks that leave something to be desired once they’re reduced to bare bones (“Rugby Child,” “Boys,” and “Exodus”), as well as the inherent disarray of these sound collages. But even the fully stripped-down number “Mary Anne” fails to crack the top (or even middle) echelon of Amen Dunes’ best acoustic repertoire. The most exhilarating songs are the ones where McMahon’s melodic mastery coalesces with his stylish, throttling instrumentals, like the club-y blues-rocker “I Don’t Mind” and murky folk-jazz “Round The World.” And as ever, his gracefully rattling drawl remains one of the most captivating voices of his generation and is only enhanced by the musicality of his wordplay — like the clever, easily misheard phrasing of “become, be calm” on “Ian,” or the haphazard, pauseless free-flow of lines like “I can’t write my mind’s soft Mama I think I’m dumb” on “Purple Land.”

Though not as vocally gifted as McMahon, the influential historical figures whose voices appear via samples add to the divine scope of the record. In a bold move (and one curiously uncredited in the album’s EPK, but perhaps this recording has conveniently entered the public domain), the first voice we hear on Death Jokes is alleged sexual abuser Woody Allen, knee-deep in a stand-up bit about escaping a hanging by the KKK, followed by Richard Pryor recounting a run-in with murderous mobsters and Lenny Bruce doing an impression of a child rendered delirious from huffing model airplane glue. But to be sure, samples are, first and foremost, mood-setting devices and not tacit personal or political endorsements, and these comedian samples found on the first track of the album are amusingly on-the-nose in their shared theme of humorous near-death experiences or, well, death-jokes-iness. Other samples, especially those on album closer “Poor Cops,” are of muddier significance, like Lenny Bruce wisecracks on everything from the absurdity of his obscenity trials to the classism of accents, as well as a J Dilla interview excerpt about his frustration with strict music sampling laws.