Discovery stories don’t get much more indicative of an artist’s talent than the one that producer Gordon Raphael tells about Regina Spektor. Raphael says he first heard Spektor play at a studio in the East Village, after being encouraged to meet up by mutual friend and drummer Alan Bezozi. “I said hello, and she smiled, and I said, ‘What do you do?’” he told The New York Times. “She sat down at a piano with a drumstick in one hand and started hitting a chair, and with her left hand played piano to ‘Poor Little Rich Boy,’ all the while singing it with this big smile on her face. And I said: ‘Oh my God, this is insane, this is amazing, we have to make a record right now. So let’s start recording.’”

Of course, like all good origin stories, the truth of this one might have been stretched just a bit. Raphael first saw Spektor perform in concert in December 2002 at the Lower East Side club Tonic, and he rapturously blogged about the show shortly after for the website Rockfeedback.com:

Regina Spektor is, quite honestly, a piano-playing, drumstick-hitting, singing miracle.

Once I saw Jeff Buckley play by himself in a small coffee shop in Seattle, revealing that magical voice, guitar-playing and lyrics to a crowd of twenty people. Once I saw Chris Cornell, age nineteen playing with Soundgarden in an early concert, thinking to myself, “Oh my god — can this kid sing!” Now, I’ve seen Regina Spektor — a young woman whose music introduces an audience to the beyond; imagine Mozart and hip-hop conducted on a piano with the most gorgeous female voice you’ve ever heard. Every song tells a story, with so many details that the lyrics seem to be channeled from a stack of books hidden offstage, and these are not cute, abstract or arty in any way — in fact it may be one of the purest musical offerings I’ve ever seen, certainly among the most brilliant.

Perhaps Raphael met Spektor in the studio first, then quickly chased that up with a show. Maybe it happened the other way around. The order of it all doesn’t much matter: Raphael was intoxicated by Spektor’s talent, and with good reason. Spektor had been writing songs long before meeting Raphael, and recording them too, but those songs didn’t have much of an audience outside of the shows where she played them. They only lived on after the fact through CDs that she printed and sold herself. But I’d imagine seeing a live performance from someone like Spektor in that day and age was immediate and electrifying, the sort of thing that would stick in your mind whether or not you had a recorded counterpart.

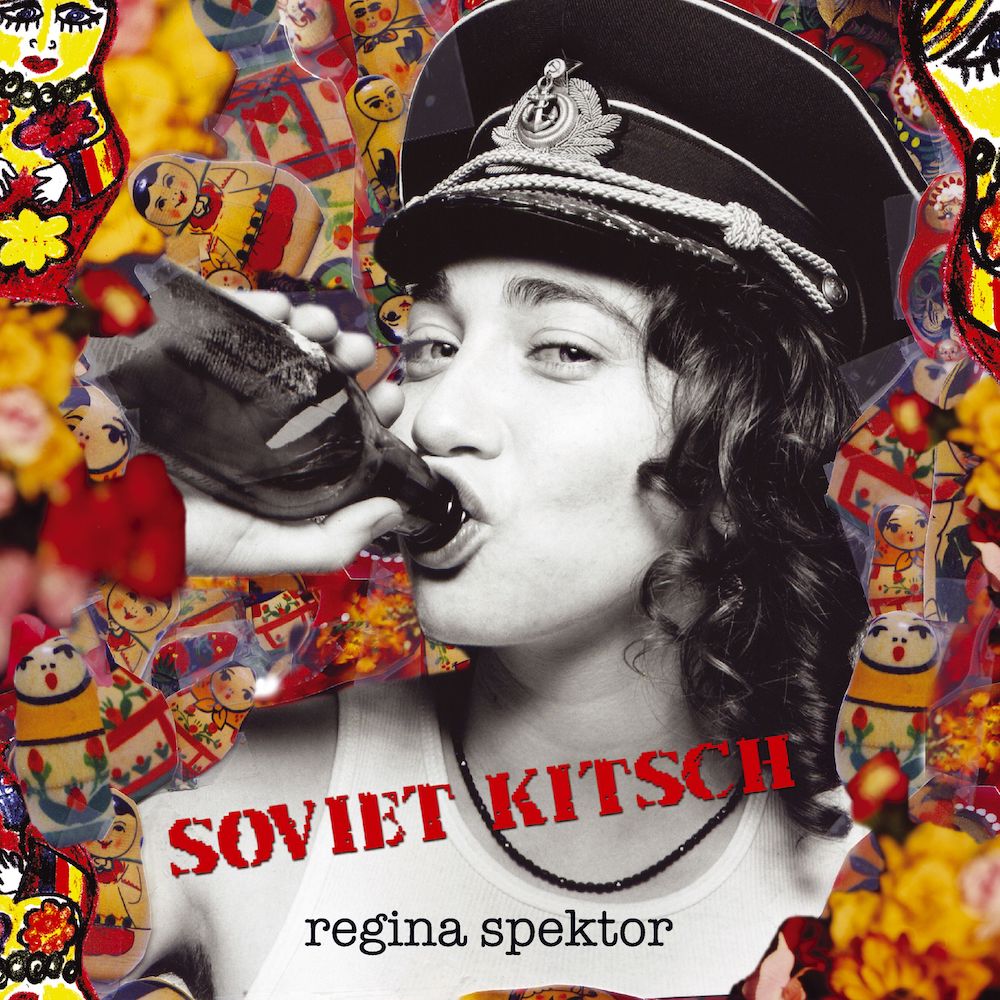

The same enthusiasm that Raphael felt eventually infected Julian Casablancas, the Strokes frontman who became an early Spektor champion. He was introduced to her music through Raphael, who made a name for himself by producing the Strokes’ debut album Is This It. When Raphael first encountered Spektor, he was putting the finishing touches on their follow-up Room On Fire. He parrots his same Spektor origin story in Meet Me In The Bathroom, the oral history of the ’00s NYC rock scene in which Spektor is a tangential figure due to her association with the Strokes. Soviet Kitsch — the album that she would record with Raphael and Bezozi, the one that Casablancas ended up getting so attached to — even gets its own brief two-page chapter in the book. Raphael was exhausted when Spektor crossed his path: “‘I’ve recorded the coolest bands in the world this year and I’m fucking tired,’” he recalled saying before meeting her. But Spektor was undeniable.

The Strokes brought Spektor out on tour with them and Kings Of Leon around the time they released their sophomore album. That tour, by most accounts (including Spektor’s own), was not necessarily a good match for the audience. “The very first day I ran off the stage crying,” Spektor recalled in Meet Me In The Bathroom. “There were these three frat boys in the front row who were like, ‘Go fucking home.’ … I played the whole set and then I dashed to my dressing room and I was just crying with mascara running down my face. Fab and Julian, they came up and said, ‘That was great!’ I was like, ‘Everybody hates me!’ They told me I had to toughen up. If I’m scared, I still think about that moment.”

Casablancas was relentless in his advocacy for Spektor’s songs. He shopped Soviet Kitsch around to record labels, many of which passed on the album despite the illustrious cosign. But eventually she landed a deal with Sire, who released Soviet Kitsch, digitally at least, in August 2004. So why are we celebrating the album’s anniversary now? Because May 2, 2003 — which happens to be 20 years ago today — is the release date listed on Wikipedia. Mind you, I haven’t found any further evidence that the date had any significance on the Spektor timeline. It’s not when she launched her tour opening for the Strokes and Kings Of Leon, which is where she first began selling her own copies of Soviet Kitsch on CD. It’s not when the album seemingly got pushed to the press, in March of 2004, when reviews started popping up in outlets like Pitchfork and NPR. And it’s definitely not when it received its first real label release via Sire, who initially put it out digitally — a novelty at the time, touted by the Times as “an unusual arrangement that would allow maximal promotion time” — before giving it a more traditional physical release in February 2005.

But Spektor’s early career does not really obey strict linearity. She’d play songs live for years before they would finally make their way onto an album. Two of the best songs on Soviet Kitsch, “Poor Little Rich Boy” and “Ghost Of Corporate Future,” had long been a part of Spektor’s sets. There were similar release date open-ends when I looked back on 11:11, Spektor’s debut full-length, which she first distributed at shows and didn’t even release officially until the album’s 20th anniversary. And we slid right past her second album, Songs, both because it’s more of a more transitional work and because it still hasn’t seen an official release, despite being sold at shows throughout 2002. During this period especially, Spektor was writing a hell of a lot of songs — it would have been hard for any traditional label to keep up.

And the release date litigation is at least a part of the narrative. In a 2004 interview, right around when Soviet Kitsch was making its way online, Spektor grumbled about its long turnaround time. “My album was just sitting there,” she told MTV. “I’d make copies and sell them at shows, just to get it out in some form. I’d feel like crap, because some sweet person would come up to me after a show and ask, ‘Where can I get your CD?’ And I’d say ‘Nowhere.’” Even Soviet Kitsch’s digital release was met with a raised eyebrow: “I’m disappointed, but I understand why they’re doing it,” she said. “People who want it can get it now, and the company won’t do a half-assed job of promoting it when the album comes out in stores. But if it were up to me, I’d love for it to be in stores tomorrow.”

It’s never a bad time to celebrate Soviet Kitsch, probably the finest group of Spektor songs collected in one place. She’d have higher individual highs on later albums, as she twisted her idiosyncratic sensibilities in poppier directions, but every song on Soviet Kitsch hits, and all of them in a different way. And the word-of-mouth long tail of Soviet Kitsch feels oddly appropriate for an album that’s so intimate but also so brash — it’s an album meant to be passed around incredulously to friends, one where every oddity eventually becomes a charm.

Most would arrive at Soviet Kitsch unprepared for it, either by way of Spektor’s association with the Strokes or, just as likely, when traveling backwards in her discography after her 2006 breakthrough Begin To Hope. Though that album has some prickly tracks, Soviet Kitsch is on a whole different level. Spektor gasps and snarls and chirps and screams; she bangs on drums and keys and throws her body around and breaks the clamor up with a breathy whispering track recorded with her brother Bear. Soviet Kitsch probably comes closest to recreating the experience of seeing Spektor live, where you never quite know what’s going to happen next.

The album begins with “Ode To Divorce,” a sweeping murmur where Spektor glides on top of some minimal piano and strings, then roars to life with “Poor Little Rich Boy,” still a stunner of a track, where she slams that drumstick down and builds herself up to a froth while talking shit about some guy who thinks he’s smarter than he really is: “You’re so young, you’re so goddamn young,” she repeats like an excuse. Spektor perfects her form of lachrymose ballads on the next run of tracks: “Carbon Monoxide,” “The Flowers,” and “Us,” the last of which has become one of Spektor’s signature songs as it continues to find its way into movies and television shows. It’s easy to hear why that one has continued to resonate — it sounds like a love song, even though it’s real story is more complicated, a thorny warning to not memorialize the past: “They made a statue of us/ And put it on a mountaintop/ Now tourists come and stare at us/ Blow bubbles with their gum.”

Both “Sailor Song” and “Your Honor” have echoes of the New York City anti-folk scene that Spektor also found herself lumped in alongside: grimy and energetic and antagonistic. And though her punk-ish streak fit with what was going on down in the Village at the time, her penchant for dramatic narratives had more in common with Broadway. Take “Ghost Of Corporate Future,” with its Dickensian vision of a man who is visited by a specter that tells him to let go of his preoccupations with business, lest he come back home and find his children have grown and he never made his wife moan. It gets looser and more surreal as it goes: “People make you nervous/ You’d think the world was ending/ And everybody’s features have somehow started blending/ And everything is plastic/ And everyone’s sarcastic/ And all your food is frozen/ It needs to be defrosted/ You’d think the world was ending…”

Spektor has written few songs more affecting than “Chemo Limo,” her six-minute flight of fancy told from the perspective of a mother who decides not to pursue cancer treatment and instead wants to spend that money to take her four kids on a trip in a limousine. Mawkish descriptions of each of those children are punctuated by emphatic, nauseating declarations about how expensive it is just to survive a little bit longer in our cruel health care system: “No thank you, no thank you, no thank you, no thank you/ I don’t have to pay for this shit/ I couldn’t afford chemo like I couldn’t afford a limo/ And on any given day I’d rather ride a limousine.” Spektor is infectious in her insistence that she is going to go out in style, buzzing and burbling as her character attempts to hold on to whatever dignity she has left. It’s tremendously sad but also oddly and defiantly invigorating, in the way that Spektor can so often be.

Even if one were put off by the affectations, it’s hard to deny Spektor’s talent. Both in that voice — acrobatic and capable of being raspy and smooth and everything in between — and in the beguiling and occasionally downright confrontational compositional choices that she makes. Soviet Kitsch represents the peak of those singular choices — accomplished and poignant and severe. To some, these songs might come across as being weird for the sake of being weird, but to me they’ve never sounded anything less than honest. It’s why Soviet Kitsch stands up so well these 20 or so years later, far removed from how she was first discovered, after she’s spent decades rounding out her discography. The songs on Soviet Kitsch are raw, vibrant, and exhilarating. They leave an impression that continues to cause people to sit up and take notice, one that would lead a tired producer to exclaim: “Oh my God, this is insane, this is amazing, we have to make a record right now.”