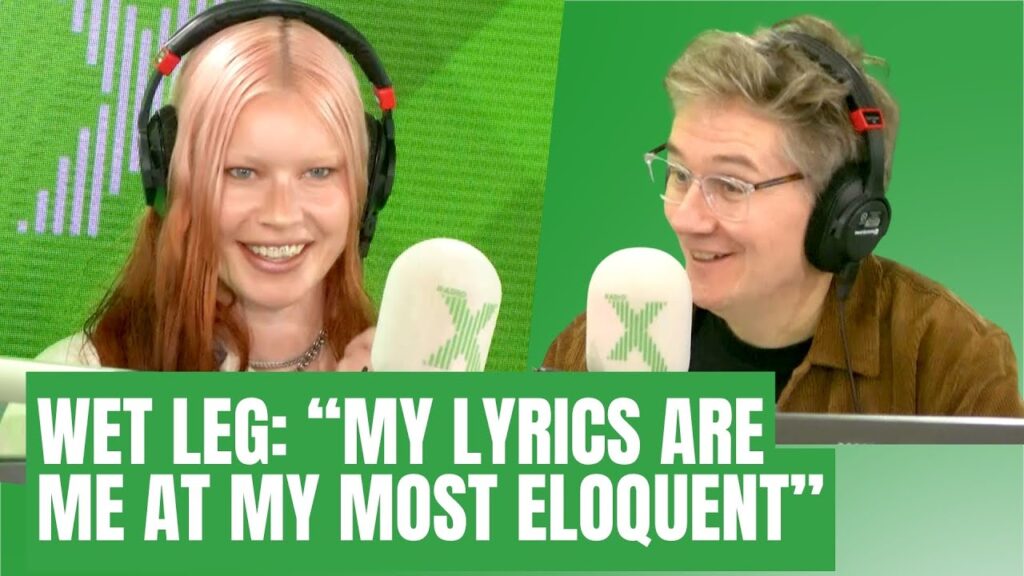

Like many who heard it at a pivotal point in their lives in 2013, Chvrches’ breakthrough debut The Bones Of What You Believe holds a striking place in time for me, but it’s lost none of its luster even as it turns 10 today. The synths and melodies still feel fresh and vibrant, the hooks are still iconic, and frontwoman Lauren Mayberry’s voice still carries just the perfect balance of bright tones and barely concealed melancholy.

The Glasgow trio looks back just as fondly on the moment when they helped drive a revival in the synth-pop scene, even if they see their 2013 selves as entirely different people. “Whenever people tag me in interviews from that time period, I’m just shocked,” Mayberry reflects in our Zoom conversation. “I look at it and I seemed fearful and concerned.” She says her experience with a sudden public spotlight on her at 23 often made her say things in interviews that she had heard men in bands — including Chvrches’ Iain Cook and Martin Doherty (AKA Dok) — say, because she assumed they knew more about what they were doing. In reality, Cook and Doherty were also in “uncharted territory,” as Cook puts it, dealing with sudden blog hype and expectations for live performances that far surpassed anything they had seen in their earlier bands Aereogramme and Julia Thirteen. “I knew what failure looked like,” Doherty adds, “and I was starting to think that time was almost up for me. I was a very anxious person who considered himself a failure, and was very eager to prove to the world I had something to offer as a creator. I wish I could go back and tell myself that everything was going to be okay.”

The story of Chvrches’ beginnings has been well-documented, from the time they dropped their first song “Lies” on Neon Gold’s blog in 2012 to the high-profile release of The Bones Of What You Believe the following year, but there are some common misconceptions about it. For instance, while many profiles mentioned that Doherty and Cook met at university, they often left out that Doherty was a student in a class Cook was lecturing (and caught Cook’s attention with a PJ Harvey shirt).

“Initially,” Doherty says of working in the studio with Cook, “I would always look to Iain, and my first instinct in the studio would be, ‘What do you think?’ Like I was asking a tutor.” He began getting invited onto projects and added to gigs as Cook started vouching for him, which grew into Cook asking him to collaborate on what would eventually become Chvrches in 2011. Though synths drove the sound of the band even at its earliest, the two were approaching them using their background in indie rock. “We’re rock guys at heart,” Cook notes. “When that mentality picks up a synthesizer, you’re going to gravitate toward certain things.” Their influences ranged from their obvious forebears — Depeche Mode, Erasure, Prince, Hounds Of Love-era Kate Bush — to more contemporaneous touchstones; Doherty in particular was drawing from a newfound appreciation for Rihanna.

When Cook produced an EP for Glasgow indie band Blue Sky Archives, he found the missing piece in his new project. Mayberry, who sang and drummed in that group, initially thought the sound of this new band would be similar to Cook’s past work: “There wasn’t a lot of non-guitar music happening in Glasgow, and generally in the UK. I would get to do this with people whose bands I really liked and I didn’t expect anything beyond that.” Doherty was initially inspired to have Mayberry provide backing accompaniment to his own lead vocals, mimicking the dynamic between Jenny Lewis and Ben Gibbard on The Postal Service’s Give Up, which incidentally also celebrates an anniversary this year. (“Without that record, there is no Chvrches,” Doherty says.) But he discovered she had “the perfect electronic voice” as soon as he heard it — “The frequency was so pure that you could drive the bass and go as far as you like with the production.” He brought Mayberry in to record backing vocals, and then muted his own vocals during playback so she could hear her parts over the tracks on their own. “It was almost like the sound jumped out, fully formed,” Cook muses. “It was like, ‘This is the next 12 years of your life.’”

With the record that followed from these sessions turning 10, and the band’s announcement of an anniversary edition due out in October, I got in touch with Chvrches to go over each song on The Bones Of What You Believe and the stories that haven’t been told about these tracks until now. The energy and camaraderie between Mayberry, Doherty, and Cook is still as strong as ever, each member of the trio just as eager to joke about mishaps and anxieties as they are to praise each other’s strengths. It becomes easy to see the chemistry that brought many of the earliest Chvrches songs to life, and just as easy to see how the genuine bonds the three formed endeared them to listeners over the decade that followed.

1. “The Mother We Share”

This is such an assured song for a first proper single. What made you want to put this one out with that kind of fanfare, after you had already gotten that initial blog attention from “Lies”?

IAIN COOK: We didn’t really have that many songs when we put “Lies” out. Our whole oeuvre was like six songs at that point, so we were like, “What’s the next best song?” So we put out “Recover” next, and then a 10″ early mix of “The Mother We Share.” I think it was the fourth demo we worked on together, and it was just one of these songs where when we played it to people… I had no idea that it was that much more special than any of the songs we had. But friends and family we played it to were like, “That one!” And I was like, “Really? Okay, cool.”

MARTIN DOHERTY: I find it difficult to choose the first song on every album. I put the album on before this call, and thought, “Wow, this is our band distilled into one song.” It starts on the I chord and fades up into all this ambience and those really hard cut-up vocals, and I thought to myself, “Holy shit, this is exactly everything we were trying to achieve in that one moment.” And we spent our whole record after that painting around that first moment in “The Mother We Share.”

LAUREN MAYBERRY: I think it felt more emotional to me, out of the handful of songs you guys had before I met you. I remember being in a car with my friend Ross [Rankin] who played in Blue Sky Archives and playing through the demos, and he pointed out that one. It felt more emotional. Like, “Lies”… I love her, but she’s not a hugely emotional song to me. It’s more about the fucking vibe and intent and the darkness. “Lies” is so muscular. Whereas I feel like “The Mother We Share” feels more human within the android universe.

It has that encapsulation of what Chvrches would become. It has delicacy and compassion, but it does still have that bite to it. I imagine that balance has stayed important to you over the years?

MAYBERRY: I think so, yeah. We always say that the quintessential Chvrches song of that era is balancing the light and the dark. That’s where we’re at now: How do you take this pretty well-established blueprint and take it somewhere else? When you get those ingredients right, those are the songs that always rise to the top of each record.

Since we’re talking about beginnings, what were those initial sessions in Iain’s basement studio like?

DOHERTY: I remember things happening really fast and a lot of panicking to turn the record button on to catch lightning in a bottle. A lot of “You have to record me right now, otherwise I’m going to forget this! This vocal idea is the best vocal idea anyone’s ever had!” It was the first time I had ever played around with hardware synthesizers in the studio, most notably The Juno-106 and the Moog Voyager, both of which became the cornerstone of the whole album. There was something so new and exciting about being able to run up to the synthesizer and touch it and make something I would have never gotten sitting at the computer, which—up until then—was my entire experience making music.

MAYBERRY: I don’t remember a huge amount about that time period, to be honest. I just remember being late to that first session, feeling awkward, and doing the thing and feeling self-conscious. The rest of the time, I’d come after work, and there’d be a lot of dark evenings where I’d sit in the back on the couch.

COOK: Drinking tea and clacking away on your laptop.

MAYBERRY: Half doing my day job, and half “Can I write lyrics for that? No?”

COOK: [laughs]

MAYBERRY: Well, [you had] a bunch of songs that already existed! I just wanted to be around and get immersed, get you used to my presence. Then, later in the record, there was more space [for me to write lyrics].

DOHERTY: The energy between Iain and I was very electric. After being teacher and student — and friends — for many years, we had never actually just worked together on a new project. We were making music with a total disregard for what anybody thought. It was outside the comfort zone of both of our musical outputs up until that point, but very much embracing music we loved that we never tried to represent in the foreground.

COOK: Martin and I would be sitting side-by-side at the desk, throwing ideas down and seeing what stuck. It’s interesting going back to those very early demos of “The Mother We Share” — they’re so densely packed full of instrumental ideas! I’m really glad we had the perspective to start stripping them out, to let the song breathe more. There was just so much going on, and it was so loud and compressed! We were just trying so hard — too hard! But it was nice to feel the lightness of the song come out, because we could’ve so easily ruined that song.

DOHERTY: It was the moment that almost wasn’t, because we changed it so many times. I love the cliché “some songs take five minutes, some songs take five months.” This is definitely more on the “five months” end of the spectrum. We agonized over every detail, but we were always trying to take things away. There’s versions of this song that just have way too many things in them, and we were like, “What can we do to focus this a little bit?” But we were making wholesale changes to the DNA and structure of the song right up until the very last minute that we released it. The verse of the song used to be a post-chorus. We’re releasing a couple alternate versions with the anniversary edition of Bones just for fun, but there are even weirder versions than those.

MAYBERRY: To this day, I think you guys are very good about zooming out of it. Deleting things from a track is as important as putting things in, if not more.

It kind of allows breathing room for a first-time listener to get acclimated to your sound and what you’re going to be doing the rest of this record.

DOHERTY: That song was the most special thing. It was the paradigm of “You better put your strongest music right up front, otherwise no one’s gonna want to listen to it.” If you wanna get noticed, you better lead with your best foot.

MAYBERRY: I forgot until we started putting together this anniversary reissue that it was the first song on the record, for some reason. I like that we were like, “Let’s just put the banger up front.” We don’t really sit down and listen to the album, because that’d be a bit odd. But it was nice to come back to it and be like, “Oh, the sequencing is nice!”

COOK: We always joke that the only time we’d listen to the albums back once we finish is when we’re in record stores doing signings, because they’d just put the album on fucking loop for three hours, and you’re just like, “Make it stop.”

MAYBERRY: At least it’s less traumatic than sitting in the room while someone’s doing a vocal comp. So I’m like, “Oh, this is quite nice, it’s actually in context!” I wouldn’t want to do an in-store [signing] with vocal comp.

2. “We Sink”

It’s funny you brought up that story about layering on “The Mother We Share,” because the last chorus of this is almost the inverse. There’s so many layers there. Was that your aim — to keep adding stuff onto the end of the song?

DOHERTY: Now, we would call it maximalism. At the time, it was just indie music — our world was post-rock and shoegaze. If you zoom out of that cacophony at the end and think about it in the context of Explosions In The Sky and bands that make the biggest-sounding guitars ever, it’s easy to see where we were coming from. We weren’t trying to make an electronic record; we were trying to make an indie record with new tools.

COOK: Most of the track hung on that Prophet ’08 sequence that starts the track and a nice four-on-the-floor kick.

DOHERTY: It starts out with literally one element, and then things come in and out.

COOK: This was us in the mode of being dance producers rather than trying to write a pop song — more about building the track towards a peak at the end. It was more of a linear build. By the end, it was kitchen sink: “Let’s just throw everything in and see how far we can push it.” Always chasing that big dancey build… not quite sure we’ve ever properly nailed it, but we’ll get there one day hopefully.

MAYBERRY: “Clearest Blue” has a dancey build, or a dancey drop. I would say you did a good job there. Don’t undercut. Don’t sell yourself short, mate. That one went quite well.

With “The Mother We Share” and this back-to-back, Lauren has an especially potent ability to use the word “fuck” in a song.

MAYBERRY: I feel like a really well-placed expletive in a song isn’t really different from any other part of language. If you’re relying on anything as a crutch and a habit, then that’s not great. But it’s the same as any other well-placed, cutting line — if it’s the right thing at the right point, you’ll know. And I swear enough in my day-to-day speech. So it should feel casual. You’ll know if it feels like it’s not sitting right.

DOHERTY: If you say “fuck” in the middle of a song, but you deliver it in the middle of a line like it’s part of the conversation, it can really be unexpected and grab your attention. I’m a big fan of swearing on songs. When I’m still writing the vocal melodies, all my scratch vocals will still have accidental swear words on them. I’m really into where a phonetic sound meets a kick drum or a snare.

MAYBERRY: There was a version of this song that [Iain and Martin wrote], and I rewrote the choruses. But, to this day… “me, ah?” What’s that? I’ve made it in my head like it’s a letter to a woman named Mia: “Mia, what the fuck were you thinking?” It was like a siren; I don’t think it was a word that Martin sung. He’s a really great writer like that; he always has these really emotive shapes. Sometimes, we would write the lyrics based off what we felt it was already saying. I had to make it make sense to me. The two [f-bombs] on this album were all you guys. You were like, “Just sing it!” And I’m like, [hesitantly] “…what the fuck… were you thinking?”

COOK: That’s gotten us into trouble so many times, when you’re doing those TV or radio things and they’re like, “Don’t say fuck! Whatever you do, don’t say fuck!”

MAYBERRY: When you look at a lot of synth-pop bands from what became that trend, I do think, in my opinion, we had a bit more saltiness to us. Partly because of the production, partly because of the Glasgow-ness of it all. I love so many of those other bands, but I like that we were a bit scrappier. So thanks for the f-bombs.

3. “Gun”

This is one of the big early examples in the increasing outspokenness Lauren has taken on over the years. What was important to you about putting that side of yourself out there on this track?

MAYBERRY: When we wrote the lyrics for that, I was under the misunderstanding that somebody being a gun — being a bit of a weapon — was a thing that was commonly understood, but I don’t think it was widely spread. I think it must’ve been hyperlocal slang. I should’ve researched that before using that phrasing, because I don’t know if that song makes a ton of sense outside of that context.

As I look back on the Chvrches discography, there are a couple tunes per record that are aspirational take-no-shit feminism, which belies what was actually being experienced and what was actually occurring. Sometimes, when we play certain songs live, I feel like a big fucking hypocrite, because I know what my experiences are day-to-day, in all areas of my life. I’m glad that [those songs] exist, but I don’t actually go through life taking no shit. I actually take quite a lot of shit. [Songwriting] should all be grounded in a place of truth, but it doesn’t have to be grounded in a place of fact. Maybe in that moment, I was like, “It’d be great to hunt somebody down and be like, ‘You shut up!’” Imagine if 2013 me, or me at any point, had done that! That’d be cool!

COOK: You do it in other ways!

MAYBERRY: What, quietly in my emails? Where I’m like, [passive-aggressively] “Thank you very much.”

COOK: [posh affect] Through your art, darling!

MAYBERRY: Yeah! When I look at female artists that I loved and aspired to be, it is a lot of those people, like Tori Amos or Fiona Apple or Kathleen Hanna. But I tell myself that they don’t wake up every day and just crush all day. In my mind, as a fan, they do. But in my consciousness as a human woman, it’s not possible. So I have to give myself the same slack. But I hope that the Chvrches fans who want to believe that can believe that, and can find that in the songs. They don’t need to know that I do a lot of fighting out loud to myself in the shower, where I’m like, “And then I would’ve said—!” But that’s not actually how that happens in real life.

How do you feel your writing about those kinds of emotions has evolved over the years?

MAYBERRY: In a post-#MeToo, post-Time’s Up, post-2020, we talk about a lot of things differently. There’s things that would not happen in 2023 that were definitely happening in 2013. I’ve spoken to other women in music about it. There’s something funny about what our band represented, or what I represented, to a certain kind of man at a certain moment in time. It was a very strange cocktail. One day, I’ll write the memoir and talk about all the well-known public figure dudes in their 40s who were in the DMs being inappropriate at that time. But it’s fine: I’m aging out of it. I’m 35. I’ll cease to exist in the public consciousness any day now.

COOK: Do you think they’re still bumming up 23-year-olds?

MAYBERRY: Probably. I feel like there must be some psychology of it, if a person reminds you of a certain moment of your life. It’s very much giving Dazed And Confused.

4. “Tether”

The structure of this is fascinating. It hinges around that turning point midway through instead of a verse/chorus structure. How did that come together?

COOK: Yeah, the chorus never really arrives, does it? That one started off with some chords Martin came up with on the guitar — lots of open string droning, simple kinds of shapes. I guess the end dancey section, when it kicks in, was kind of a joke. We were taking the piss out of trance music — those fist-punching arena dance acts. That’s one of the things I really like about the early Chvrches stuff: We were just trying to make each other laugh. A lot of the time, those ideas ended up staying because they worked.

DOHERTY: I thought it was so absurd that we could have this honest and overwrought and beautiful and sad front of the song, and then have a Euphoria [breakdown]. There used to be these mix CDs in the UK called Euphoria that were hardcore trance records. I loved them. When I hear trance records, even the ones people think are the corniest, some of them still get me in the feelings. That was a $20 VST synth [on “Tether”] with a funny little arpeggiator on it. We thought, “Wouldn’t it be really funny if we just had a mad trance moment at the end of this song?” And it ended up working!

MAYBERRY: Your original lyrics for that were really cool. The pre-chorus was about Laura Palmer: “Wrapped in plastic/ Why’d you water the dead flowers?” It was a Twin Peaks concept piece. And we kept the cool, creepier lines from those original lyrics. I like that it feels slightly more emotive, maybe, but it still sits in that eerie, strange universe.

COOK: There’s something creepy about it, isn’t there? In the harmonies!

MAYBERRY: Yeah! The harmonies are so weird. I feel bad — whenever I perform it live, I have to take them totally out of my ears because it messes with my pitch too much.

COOK: I feel like we accidentally pitched them up to the wrong interval, and it created this really weird dissonance. And then I think you took that and rounded off a few of the notes to make it work, but kept the weird intervals in there too.

MAYBERRY: If they were more traditional harmonies, they would lose all that edginess. Happy accident!

COOK: And then it goes into a big trance bit at the end! For no apparent reason!

MAYBERRY: But then you get to do cool guitar stuff in that. Live, that’s always really good. And then I’ve got nothing to do for ages, so I just… [mimes punching the air].

As a tribute to the scene?

MAYBERRY: If you’re gonna lift from it, you should pay homage.

5. “Lies”

Here, it’s important to talk about this being the first song you ever dropped, via the Neon Gold blog, with very little biographical info and fairly anonymously. What compelled you to release it that way, and how did you settle on this song?

DOHERTY: That one was born out of observing culture at the time. The first music Iain and I ever wrote was witch house. We thought we were going to be a witch house act where all our song titles were symbols. The idea of confusing people and telling people all the lies you could about who you were and what you were doing was something I saw as a big bonus. That was where counterculture on the internet was at the time.

COOK: That one and “The Mother We Share” were our two favorites at the time. There’s something about it. It’s quite bombastic and — as you said earlier, Lauren — muscular-sounding.

MAYBERRY: Yeah! And it’s a good statement of intent. The record is that balance between the candy and the fucked-up creepy. The imagery and sound of “Lies” links into “Science/Visions” and “Tether.”

DOHERTY: We were totally unsigned at that point, so there was no real plan other than us discovering that if you put out a song online that blows up, the next time you put out a song, more people will listen to it. And if you do that two or three times, then you might get a record deal. But no one that I could see had converted that to a bigger career at that point.

COOK: It was definitely the right decision to release it anonymously and not have it be considered as a project with history, or to have it compared to the old bands we were involved with — to just have it be a totally fresh sound. I think that was probably the right decision. I think it could’ve totally backfired and had nobody give a shit.

MAYBERRY: I think that speaks to how much we didn’t expect it to go as wide as it went. From my perspective, that decision was so people in the local scene wouldn’t go, “Oh, it’s that guy from Aereogramme, and that guy from Julia Thirteen, and that girl from Blue Sky Archives.” We were thinking more about that than anything outside of that.

It sounded like you had a lot of jitters surrounding the expectation of live shows and press after this song blew up, given that you hadn’t had a sense of how you would operate as a band beyond the studio. How do you look back on that time?

DOHERTY: There was a whole new layer of pressure, trying to become a live act that came across like we knew what we were doing, when we had made only six songs and I couldn’t tell you how to play the chords for any of them. It was a studio project first and foremost. We had to create a live band to play music that people already liked, as opposed to starting a band and trying to create music that people might like. The whole thing was ass-backwards. So there was an aspect of terror, because it would be the first time there would be any attention on us. A&R people were coming to our first gig. The idea that our first gig was an anticipated event was completely alien to me — and I realize now that was not normal. I wouldn’t have changed any of it, though, because that was one of the signs that things were going to be different.

MAYBERRY: I feel like the recurring theme is me being like, “It was terrifying. I didn’t want to let anybody down or let myself down.” Now, I know more about the tech, and how involved that is, even if I don’t know how to do it. We didn’t have a designated playback person to build us [live tracks]. Iain just did it in the studio. That’s bonkers! There’s people who get paid a lot of money to build those things for people!

COOK: I think we ended up doing Coachella in front of 35,000 people with that same setup, without a monitor engineer, which is really bonkers when you think about it. It went wrong a lot as well! It really did fuck up a lot, particularly when it was hot or dusty, because we used the old Macbooks with the optical drives in them. As soon as you have a big thump of sub next to the laptop, it skips. We didn’t realize that was gonna be a problem, so we had to start getting slabs to absorb the shock.

MAYBERRY: Oh, the slab! I forgot about the slab!

COOK: We were really just learning on the job. There was no budget to employ anybody to tell us how to do it properly, so we were just trying to troubleshoot one disaster at a time. One particularly hilarious one was that we were using a Bluetooth mouse on stage—

MAYBERRY: At the Thekla in Bristol. I remember this vividly. Never been back to that venue since.

COOK: For some reason, we weren’t using the mouse that night. We were playing the intro to “Lies,” and I went to go try to trigger the verse. The mouse cursor started fucking jumping around all over the screen. And Lauren’s looking around at me like, [through gritted teeth] “Come on!”

MAYBERRY: I thought you’d lost your damn mind.

COOK: The mouse was inside a flight case at the side of the stage, and the sub-bass was moving the mouse around in the flight case. So I couldn’t get control of the mouse cursor to move onto the next section of the song. There was a lot of anxiety between the three of us, for different reasons. Looking back, massive regret not finding a way to enjoy it more. I think it was a long time before we could sit back and say, “Let’s just relax and enjoy what we’ve built.” But there’s always something else to worry about, isn’t there?

6. “Under The Tide”

I assumed that this was written when Martin was still planned to front the group, rather than after you decided to have Lauren take lead vocals.

MAYBERRY: Yeah, I remember that one being later in the process. I wrote the lyrics on it, and then Dok sang it.

DOHERTY: It was in a weird key for you. So instead of repitching the whole thing, I sang it and we thought it was actually cool and we should keep it that way. It wasn’t a preplanned thing.

MAYBERRY: In the end, you got these sad lyrics from me. I can’t imagine me singing it — I feel like his voice works so well on that song. I know he’s not so psyched on performing it now, but maybe one day. I always think that’s such an important part of the show when it does happen. He’s a really good frontman, and a very natural performer in a way that I always admire because I don’t have that. It’s always great fun for me to watch from the keyboards and be like, “That’s the thing. He’s got the thing.”

DOHERTY: I’ve never been much of a lyricist, personally. It’s always my least favorite part of the process. When someone else wants to take up the mantle of writing the lyrics, I’m delighted to hear it. It was nice in terms of band harmony. If Lauren had to sing lyrics for songs she didn’t write, then it was only fair I would sing lyrics for songs I didn’t write.

Even after you traded vocal responsibilities, did you still want to keep vocal interplay a factor in this era of the band? There’s a lot of that across this album.

COOK: It’s always been a hallmark of the band’s sound, but we probably don’t lean into it as much now as we did on this record.

DOHERTY: That was very much in our musical DNA at that point. We were such an emo band in disguise — it was very common in emo for a second vocalist to come in and have a countermelody between the two vocalists appear. Countless artists I loved used that — the Postal Service, Jimmy Eat World.

MAYBERRY: It’s tricky to do male/female vocals without it getting a little “Whole New World” or Alphabeat. [laughs] It’s a delicate balance! It just needs to be the right context and the right song.

7. “Recover”

b>What’s the story behind the studio chatter right at the beginning?

COOK: “That one’s a bit tuney.”

MAYBERRY: Well, it was, probably! Based on what we’ve discussed! I don’t think I’ve ever said “tuney” before or since. I like that we kept that in. It felt very early 2000s.

DOHERTY: Wherever it’s possible to put a little Easter egg or a little funny human moment from the studio, I always gravitate toward it. That’s all over everything we do. I’ll grab something Iain will say into the mic and turn it into the hi-hat. I like having little inside jokes.

COOK: It’s just weird as well, because it’s all delay and bizarre effects. It’s like, “What did she say? Was that a secret to the meaning of the song?”

MAYBERRY: Nope! It’s just self-doubt! The lyrics for this one were you guys, and they’re about paper fortune tellers. That was cute. And “open the envelope” means “on the synth.”

COOK: No, it doesn’t! A lot of people think that, though! How do you describe the flap [on the fortune teller]? “Open the flap,” isn’t really a good lyric, Lauren.

MAYBERRY: No, it’s not, and I wouldn’t like that.

COOK: [singing] “Open the flappy bit!”

MAYBERRY: [laughs] I never know which way around “part ways” and “old ways” go in the chorus. I would get it wrong so many times, that the way I had to remember it was: “it’s not alphabetical, it’s ‘post office’—’p’ comes before ‘o.’” So it’s “part ways” the first time and “old ways” the second time. And that’s quite weird that my brain, still, as I get to that bit, is like, “Post office. Post office.”

COOK: “Recover” really resonated in a lot of people we meet. We used to get people coming up who had substance problems, saying it really helped them.

MAYBERRY: And people who have had problems with illness. It’s always quite an emotional one live. I suppose that synth part is very triumphant. We write enough bummer sad songs, so it’s nice to have something looking up.

COOK: It is quite upbeat and uplifting, but there’s a strong vein of melancholy going through it, like all the best shit we do. That balance of happy-sad.

8. “Night Sky”

This is another structurally interesting one, with these really quiet verses and big explosive choruses.

DOHERTY: The reverb on the drums was the AMS [RMX16] that was used on a lot of Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel records, and we wanted to do that tom explosion sound on “Hounds Of Love.” This song was an interplay on how tight we can make the verses and how big a statement we can make when the chorus explodes. When it opens out, it’s all bashed hi-hats and toms versus very dry and close vocals right in your face.

MAYBERRY: Was this one quite early in the process?

COOK: It was definitely earlier. It was in the second batch [of songs we wrote], because we played it at our first show. The thing I like about the chorus is that it feels quite restrained to me. There is a lift, but it’s almost like the coolness of the guitar line is pulling back, and it creates a weird tension that’s almost anti-euphoric. The vocals are often misheard as, “I’m a nice guy,” which we don’t love.

MAYBERRY: I mean, it’s a nice sentiment! It’s one of the most positive things I’ve ever said about myself, probably. It’s funny, those things I don’t think about. I think that was just an experience thing in lyric-writing. You’ve obviously written lyrics before, but that wasn’t your primary job.

COOK: Not since high school. [laughs]

MAYBERRY: Now, we would be like, “That one sings funny,” or, “That sounds weird when you put it together like that.” Things where you spend hours on it and probably flag it now. But there’s one in “Gun” where people think, because of the Glaswegian pronunciation of “back,” it’s “stuck in the knife that you held up my butt?” Which, obviously, it isn’t, but enough people have said that. So, you know… he who is without sin… I can’t comment. [laughs]

How were the cut-up samples of Lauren’s voice in the bridge implemented?

COOK: We had a little MPC50 — like one of the wee, small ones — and we just loaded a bunch of Lauren’s vocal samples and mapped it out. It was just a case of us jamming on the pads and coming up with sections that could be repeated riffs and tweaking [accordingly]. It wasn’t mapped out with a mouse or consciously sculpting that part — it was very much about the feel. Which, I think, is how we did the vocal riff on “The Mother We Share” as well, just jamming about on the pads and being like, “Wait, wait, stop! That’s the one!”

DOHERTY: There was always an MPC on the desk and we would use that right at the start of the writing process. It’d sometimes be like, “Let me play some drums over this!” It’d be how we’d decide if a song was too fast or too slow, or needed half-time or double-time. We were listening to The Art Of Noise and Laurie Anderson and the earliest forms of sampling, sounds that would come from Kate Bush records. Those were the things that informed us going searching for that, but it wasn’t about just taking from the past. I was listening to Caribou records at the time — Caribou is still a huge band for me. Those psychedelic jam moments where, suddenly, everything goes a bit crazy — that was our idea. Sometimes you’re just gonna have to grab people’s attention again and change something entirely, just when you think you know what the song’s going to do.

9. “Science/Visions”

This is one that’s really endured live for the band, even as you’ve taken some of the singles out of the rotation. What makes this one a favorite among the group?

MAYBERRY: I just don’t think there’s anything like this in the Chvrches canon. It’s spiritually connected to stuff like “Lies,” but it’s scarier. It makes sense to me that, eventually, we made an album that was horror-infused, because that’s always been a part of it. The call-and-response vocals are really cool; we don’t have that anywhere else. I still really love the recorded version, but I like that the live version grew to be this darker, rockier, Nine Inch Nails-ier vibe. It always changes the energy of a live show when that one comes in. It’s like, “Oh, right. We’re not fucking around.”

DOHERTY: That one’s probably my favorite song on the album still. That’s the one where, even when I heard the recording, I thought, “This is the band that we were trying to be.” The live version has me playing this really aggressive Siouxsie And The Banshees-style post-punk guitar across the whole song. When I hear this song, I think about Brad Fiedel as a composer, and Kate Bush with those nonstandard harmonies and vocals all running into each other — like on the second half of Hounds Of Love. When you get into the deep swamp of an album, by track eight, you want something new and surprising and very different tonally. So it was very natural for us to go dark and ’80s and borderline techno.

COOK: It’s always a great pivot track live. Even though we’ve got four albums of stuff, a lot of the time, when you’re putting together a sequence of songs for a live show, you realize that a lot of them are a similar energy. This is a great one to pivot from one section of a set to another, because it’s kind of a palette cleanser — as Lauren said, we haven’t really got anything else like it. And it does allow us to throw ourselves around a bit and rock out and make a terrible noise, which is always fun to do. Some of the lyrics from that were almost straight lifts from the Tibetan Book of the Dead. I was just running out of ideas and flipping through and was like, “Maybe if we just rephrase this slightly, it’ll sound mysterious and cool.” It’s actually quite spiritually on the light side of the spectrum rather than the dark, industrial, Nine Inch Nails thing, but I guess the juxtaposition of those chromatic brooding chords makes the whole thing seem quite sinister.

10. “Lungs”

Is that sound at the beginning Lauren? How did that come to form the backbone of the song?

COOK: I think that exhale’s Martin!

MAYBERRY: I think so! But I like that you thought that was me. You were like, “She’s got that in her.”

DOHERTY: That’s me at the end of the vocal take, being like, “That was a tough one. That was a mouthful.” And me and Iain were like, “Let’s turn this into part of the beat!”

COOK: Yeah, just a percussive element. I feel like this was another one we were doing just to make each other laugh. It’s quite silly and playful, apart from the lyrics.

DOHERTY: This one was producers trying to make each other laugh, but Lauren brought a different perspective because she was on a different wavelength with the lyrics she was writing. It probably wouldn’t have worked if she had tried to write some kind of comical lyrics. There has to be some balance somewhere.

MAYBERRY: I’m sorry, I wasn’t aware we were having fun. That’s over. It’s finished now. But I think that was the first full set of lyrics I wrote.

COOK: “Gun” was the first one, wasn’t it?

MAYBERRY: Was it? Maybe they were the same week.

COOK: I feel like you were in Edinburgh and sat in the park with a notebook and wrote down a bunch of lyrics for those two songs.

MAYBERRY: Oh yeah! In Waverley Gardens. I had to go for work or something, and I had red light fever. That still happens to me to this day. Sometimes, you’re in the right headspace and you can get something right away, and sometimes you can’t. Now, I just try not to worry about it too much, and it’ll always come when I’m walking around or on a train or in the shower. You’re still doing the work of poking at the song — it’ll always be lurking in there. I used to get so freaked out about it, because I felt like I was asking for the space, but I’m not up to putting up the space. And that’s the worst headspace to try to be in for writing things.

There’s the moment where Iain gets to break out the bass too. What’s it like bringing your indie rock experience into this otherwise synth-driven band in moments like that?

COOK: That was always a lot of fun to play live. We doubled up the bass guitar with a synthesizer playing the same part. People would always come up to me and ask, “How did you get that bass sound? It’s absolutely insane!”

DOHERTY: The beginnings of the song were Iain and I wondering if we could make a song that has only two chords. In order to do that, we discovered we had to have moments of real explosion that would grab your attention outside of the harmony. We had a Moog behind that really distorted bass guitar — that’s a Nine Inch Nails thing. There’s also a Lauren sample there that used to be a Nicki Minaj sample, but we had Lauren replace it because that was the kind of major label artist that would come after you.

11. “By The Throat”

The title drop on this song is about possessing bite, but it’s still so deeply vulnerable in a lot of ways. Do you see it fitting in with the other tracks in that way?

DOHERTY: Our entire career has been that conversation. That thread runs through everything we do. The day that we put out Bones, I knew we were doing something I believed in wholly because we did a Radio 2 session — which is like a BBC station for old people — and a Boiler Room set on the same day. Whatever bizarre mixture we all bring to this can apply to all audiences, and that’s why I still don’t shy away from us ever being too pop or too dark. Those two things are just facets that have always been there. This whole album, to me, has aged pretty well and doesn’t sound dated. But when the claps came in on “By The Throat,” I was a little sad because that was quite trendy at the time and something that hadn’t dated as well. But that’s the whole point of records: they’re supposed to make you feel different things after 10 years than they made you feel at the time.

MAYBERRY: When I think about that song, that’s one of a handful of songs about the experience of signing the band. Obviously, we were so lucky for what was happening. It was this thing that we all wanted since we were kids, but all that glitters isn’t always gold, necessarily. What that experience actually entails — you think that everybody in your life is gonna be really happy for you, and it’s gonna be an easy decision to make and it’s all gonna make so much sense, and everyone is gonna be getting on the best they’ve ever gotten on and feeling unified — it isn’t like that, in my experience. I don’t know if that’s the experience of many people I’ve met. It doesn’t look like what you thought it was going to look like. But you can’t say that out loud to people you’re in a band with at the time, because it’ll scare them. So you write it in a song and scare them that way instead. They’ll be like, “Oh my god, she’s gonna quit!” And I’d be like, “No, it’s just a story!”

You’re just assuming a voice!

MAYBERRY: Yeah! “Guys, it’s a character! I’m a very narrative writer, clearly.”

COOK: There’s definitely a thread, isn’t there, with “How Not To Drown” as well — a very similar lyrical thread.

MAYBERRY: Yeah, it’s interesting — people always assume that I’m writing about “the man” or an ex-boyfriend, and a lot of times, I’m writing about neither of those things. Sometimes, you do write about cumulative experiences, but I think it is interesting that, because of the politics assigned to the band and because I’m a woman, people assume I’m writing about that a lot.

I like the imagery of this one, but we were gonna call it “Bad Blood.” And then two songs called “Bad Blood” came out in quick succession — Bastille and Taylor Swift. We’re on the same label as Bastille and got a heads up they were going to have a song called that. And then when Taylor Swift’s came out shortly after, we were like, “Phew! Good thing we changed that!”

12. “You Caught The Light”

Was it intentional to have Martin take lead vocals at the end of both sides of the record?

COOK: When we were sequencing it, we probably discussed the symmetry of doing that, but it certainly wasn’t by design.

DOHERTY: I never thought about it until right now, but that’s kind of cool.

COOK: We spent a lot of time sequencing that record. I remember sitting in the tour bus somewhere in America, having endless “heated discussions” about what songs would go where. Such a difficult thing to do if you’ve never had to do it! This just seemed like such a great closer, because it’s so dreamlike and epic. It’s a great way to come down after the journey we’ve all been on. I’m glad that we never got sued by the Cure for that song. [laughs]

MAYBERRY: We were very lucky with that, because it’s definitely “referencing” a lot of things. If anything, that’s the one we should’ve had Robert Smith on. We were like, “We have to spend a decade finding him and befriending him, and then he probably won’t sue us.” We’re quite good, if I may say, at closing tracks. We don’t think about writing a “closing track,” but sequencing it like a good cinematic “ends this chapter, but opens a page for the next thing” kind of thing.

DOHERTY: That being a closer is natural, because it’s expansive and sad and wistful and makes you think on things. I like closers that point to where you might be going afterwards. The fact that we finished the first album with “You Caught The Light” — very influenced by Disintegration — and could one day go on and make a record with Robert Smith… that’s the greatest achievement for me as a musician for the longevity of this band over 10 years. That’s the number one reason why I still do this, and will hopefully continue to do it.

COOK: Martin’s vocal performance on that track is unbelievable. There’s something really epically mournful about the way he sings that.

DOHERTY: From inside the studio, it might be a little self-indulgent to make a six-minute-long slow, bass-led song. So if the moment does strike, it feels important to really do it.

When you think about where this track, and this album, left you at this stage of your careers, how do you see this album now in terms of how this album set you up for where you took Chvrches from here?

DOHERTY: It’s exactly where it’s supposed to be for me, as a creator: It’s the first statement in a new era and the building blocks from which all things came. In any aspect of what we do, the DNA of what we do is somewhere on this first record. It’s a very rough-sounding record and very fun, and I can tell we were making music with the type of abandon I’ve been trying to make music with as I’ve gotten older. It sounds so innocent to me and so fun, and I’ve been trying to get back to that for 10 years. I don’t know if I’ve ever truly done it. Sometimes, I can hear us giving too much of a fuck about what other people are going to say. On this album, I don’t hear any of that. My ultimate journey as a creator is to get back to that feeling. This record will be with me forever.