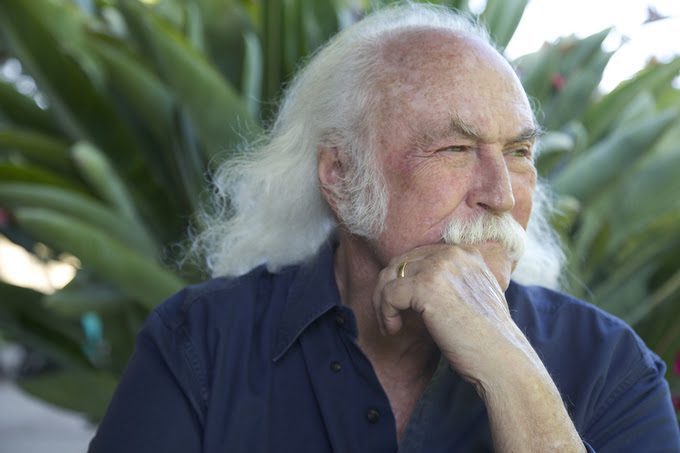

David Crosby made it to 81! That’s pretty good! Crosby didn’t outlive famous ex-bandmates like Stephen Stills, Graham Nash, and Neil Young, but he made it a whole lot longer than anyone could’ve reasonably expected. For those of us who were born after Crosby helped change the sound of popular music, the man might’ve been more famous for being a drug-damaged mess than for being quite possibly the greatest harmony singer in rock history. For many years, Crosby was frequently mentioned alongside Keith Richards as one of those guys who simply couldn’t die, despite his own best efforts. But nobody lives forever, and we lost David Crosby late last week.

David Crosby’s loss wasn’t exactly a shock, but it was still jarring. Crosby was always present, always visible. Crosby was available, and he was never shy about expressing an opinion. In the last six years, Stereogum’s Ryan Leas interviewed Crosby three times; I always got the impression that Croz and Ryan were basically friends. Crosby also went through a remarkable artistic rebirth. After nearly 20 years without releasing an album, Crosby came out with Croz in 2014, and then he never stopped. Crosby’s five late-career albums were all lovely, committed works, and his voice sounded like it hadn’t aged at all. His final LP For Free came out in 2021, and it was beautiful.

In retrospect, David Crosby’s life looks like some kind of American epic. He’s the son of the guy who did the cinematography for High Noon. He kicked around the storied early-’60s folk scene and then found sudden fame as a crucial part of the Byrds, a band whose sound completely altered the course of pop history. After a tumultuous run as a Byrd, Crosby got himself fired and then became even more famous, getting together with a few other famous cast-offs and starting one of the first-ever supergroups. That band’s story was tumultuous, too, but they gave us even more music that helped define a very different era in American music and culture.

David Crosby’s dark period was very dark, and it was long. The stories about his demons — the prison stay, the liver-replacement surgery — immediately became the kind of rock lore than you learn when you start buying copies of Rolling Stone as a kid. (The press also went nuts over the fact that Crosby was the biological father of Melissa Etheridge’s children, as if it wasn’t just a guy doing a nice thing for his friend.) But Crosby overcame those demons, and he stuck around. He made more music. He mended some old bridges, and then he gleefully set plenty of others aflame. He took to Twitter like a fish to water, and he kept himself in posting overdrive right up until the very last day of his life.

For years, when an iconic figure in music history would pass away, I would celebrate that figure by writing a piece that would go all through the flotsam of their career. These pieces aren’t exhaustive biographies or lists of their greatest achievements. They’re just fond, haphazard trips through different iconographies — a bit like what we at Stereogum like to cover in our We’ve Got A File On You interview series. (David Crosby himself did one of those interviews in 2021.) I wrote pieces like that for Prince, David Bowie, Chuck Berry, Tom Petty. I haven’t written one since we lost Aretha Franklin in 2018, but I’m compelled to salute the man in the same way.

1. “MR. TAMBOURINE MAN”

Please forgive me for being basic, but there’s a reason why this song is the obvious place to start this list. David Crosby wasn’t the driving force behind the song that made the Byrds famous; he didn’t even want to record the damn thing in the first place. But the Byrds’ cover of “Mr. Tambourine Man” is a big-bang moment, a pivot-point in the entire history of popular music. You could argue that other acts combined folk music with rock ‘n’ roll before the Byrds, but nobody did it with anything like that band’s earthshaking force. The single’s success also represents a fascinating point in pop history — a time when nobody quite understood what they were doing, when everyone was still fumbling around in the dark. A few months ago, I published a book with a chapter on “Mr. Tambourine Man,” so the whole saga is fresh in my mind.

The short version: The Byrds were all familiar faces in the early ’60s folk scene, but all of them had their minds blown by the Beatles, and all of them immediately started growing their hair out. Drummer Michael Clarke was recruited specifically because he had some great Beatle hair; he didn’t own a drum set. With Crosby, the story is that he heard Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark harmonizing on a Beatles song in a nightclub stairwell, and he joined in. All of this happened in 1964, the same year that the Beatles arrived in America.

The Byrds went through a few name changes and ultimately signed to Columbia, a label that had previously disdained the entire idea of rock ‘n’ roll. The band’s manager brought them an acetate copy of “Mr. Tambourine Man,” a song that their labelmate Bob Dylan had written, before Dylan’s version came out. The Byrds were reluctant to cover Dylan’s song — Crosby didn’t think he was any good — but they ultimately cut out a bunch of Dylan’s lyrics and reworked “Mr. Tambourine Man” into something resembling a pop song.

Producer Terry Melcher, son of Doris Day and future target of Charles Manson, didn’t think the Byrds were good enough musicians to record “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and he didn’t let any of the non-McGuinn members play on the record. Instead, he replaced them with members of the Wrecking Crew, the informal crew of Los Angeles session-musician aces. But Crosby still harmonized with McGuinn and Clark on “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and the song became a defining generational moment.

“Mr. Tambourine Man” was the Byrds’ second single and their first for Columbia, and it went to #1 on the Hot 100. The Byrds were marketed as America’s answer to the Beatles, and they were greeted around the globe as straight-up teen idols. Bob Dylan, impressed with “Mr. Tambourine Man,” started toying around with rock ‘n’ roll himself, and he became a very strange and new kind of pop star. Dylan made hits, and he got to #2 a couple of times, but none of his own recordings ever went all the way to #1, unless you count his vocal on “We Are The World.” The Byrds did what Dylan never could.

Maybe David Crosby had more to do with the success of the Byrds’ second and final #1 hit, their 1965 version of Pete Seeger’s “Turn! Turn! Turn!” Crosby actually got to play guitar on that one, and he arranged the glorious cascading harmonies. But “Mr. Tambourine Man” was what propelled Crosby and the rest of the Byrds into immortality. Sadly, that immortality was not literal.

2. “EIGHT MILES HIGH”

I mean. Come on. Jesus Christ. The Byrds released “Eight Miles High” as a single less than a year after “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but the world had already changed. The Byrds’ folk-scene friend Barry McGuire had gone to #1 with “Eve Of Destruction,” a straight-up protest song that the Byrds themselves had turned down. Bob Dylan had made it to #2 with “Like A Rolling Stone.” Folk-rock had become big business. More importantly, the Byrds themselves had changed.

David Crosby wrote just one line of “Eight Miles High” — “rain grey town, known for its sound” — but the song couldn’t exist without him. Crosby had turned the other Byrds on to Ravi Shankar and John Coltrane, and “Eight Miles High” was the band’s attempt to incorporate those influences. The song is a way-out masterpiece, a stoned drone that still resonates as pop music. Crosby was more directly involved with writing the B-side “Why,” which is nearly as wiggy.

“Eight Miles High” was a genuine hit, albeit not as popular as “Mr. Tambourine Man” or “Turn! Turn! Turn!” (The single peaked at #14.) Still, it took years for the song’s influence to fully reveal itself. “Eight Miles High” helped invent spaced-out psychedelic rock, which came into full flower over the next few years. The song never went away. When the great Minneapolis punk trio Hüsker Dü were getting ready to release their canonical 1984 double album Zen Arcade, they wanted to signal that they were on some new shit, so they covered “Eight Miles High” and released it as a single.

Years later, asked what he thought of the Hüsker Dü take on “Eight Miles High,” Roger McGuinn said that it was “very creative.” David Crosby did not agree: “Didn’t get me.” I’m not really surprised that Crosby didn’t like that cover. I sure like it, though.

3. THE JFK STUFF AT MONTEREY

The Monterey International Pop Festival, held over three days in June of 1967, is generally regarded as the first major rock festival and maybe as the dawning of the age of Aquarius. It’s where Jimi Hendrix lit his guitar on fire, where Janis Joplin got discovered, and where white people started to understand that Otis Redding was great and important. David Crosby actually played at Monterey twice — with the Byrds and also with the Buffalo Springfield. (He filled in for his future bandmate Neil Young, who was on the outs with the rest of that band at the time.) At that point, the Byrds were starting to fracture, partly because Crosby was constantly high.

The other Byrds also weren’t too happy about the way David Crosby introduced “He Was A Friend Of Mine”: “When President Kennedy was killed, he was not killed by one man. He was shot from a number of different directions by different guns. The story has been suppressed. Witnesses have been killed. And this is your country, ladies and gentlemen.”

JFK had been dead for less than four years. This was not the kind of thing that you were supposed to say in front of cameras, to an audience of tens of thousands. But David Crosby might’ve been right; by now, I think more people agree with that version than the Oswald-acted-alone narrative. Crosby looked cool as hell up there, too. That fur hat was sick.

4. WOODSTOCK

I’m hitting all the obvious greatest hits up front, and you’ll have to pardon me. There’s plenty of goofy stuff worth highlighting in David Crosby’s career, but the man was also a key part of a great many moments that had huge cultural significance. In fact, he hit the grand trifecta of iconic late-’60s music festivals: Monterey, Woodstock, and Altamont. He was there for the symbolic beginning of something, and he was also there for its symbolic ending. Maybe Woodstock was that thing’s symbolic climax.

So picture this. You’ve just been kicked out of your famous band. You team up with a few other guys who are also refugees from other famous bands — Stephen Stills and Neil Young from the Buffalo Springfield, Graham Nash from the Hollies — and you start a new band. Your second show is in front of 400,000 people at a festival that soon became known as a genuine historic event. Your band takes the stage at 3AM, and you totally fucking kill it.

Soon after Woodstock, David Crosby had a big hand in the way that the festival became myth. Crosby’s friend Joni Mitchell famously skipped Woodstock to appear on The Dick Cavett Show, and she watched news reports on the festival with longing and regret, putting those feelings into a song called “Woodstock.” In 1970, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — who, after all, were at Woodstock — covered Mitchell’s “Woodstock.” Their version was a #11 hit, and it played during the closing credits of the blockbuster Woodstock documentary.

Crosby, Stills & Nash also got back together to play Woodstock ’94, which did not go quite so well. Two years ago, Stereogum’s own Ryan Leas asked Crosby about that performance, and his answer was the best:

It was awful. Absolutely fucking awful. Man, are you kidding? We went on after Nine Inch Nails. Does that give you a clue? Can you imagine us singing “Heeeelplessly hooooping” to a mosh pit? OK? Are we getting it? Is the picture coming in clear?

5. THE BACKDRAFT CAMEO

OK, now let’s get into the silly shit. The Ron Howard film Backdraft, a big summer hit in 1991, has a wild opening scene. Heroic firefighter Kurt Russell takes his adorable little kid with him so that the kid can watch him fight a giant fire — a strange parenting decision on Kurt Russell’s part. Stirring Hans Zimmer music plays as the fire engine roars through the streets and the kid gets to honk the horn. The kid watches adoringly as Kurt Russell jumps around on fire escapes and catwalks, but then Russell gets totally consumed in a deadly fireball, and his helmet lands exactly at his kid’s feet. It’s a bad day for the kid, and it’s a worse day for Kurt Russell.

About two minutes into Backdraft, David Crosby shows up. Other than a 1990 episode of a TV show called Shannon’s Deal, this is David Crosby’s first screen acting performance. He’s credited as “’70s hippie,” which is accurate, and he’s onscreen for maybe two seconds. Crosby’s character wants Kurt Russell to know that all his stuff is up in the burning building. He’s worried about his stuff! I think he does an accent? Crosby’s appearance is so distracting! It adds nothing! I love it!

6. “GLORY”

None of the albums that David Crosby released in the past decade were hits, and I can’t imagine that he expected them to be. But the music on those records is often stunning. This one hit me especially hard while I was working on this piece. Crosby released his album Here If You Listen in 2018, and he shared billing with the musicians who backed him up on Lighthouse, his previous album. At the time, Crosby said that he didn’t bill Here If You Listen as a solo album because all the songs — other than the “Woodstock” cover, anyway — were created by a band.

The funny thing about David Crosby is that he was a born collaborator who seemed to piss off his most famous bandmates so badly. He was a virtuoso harmony singer whose voice conveyed pure serenity, but he had a hell of a time personally locking in with his peers, and his life was anything but serene. On this late-career song, though, I hear Crosby generously sharing the spotlight with musicians way younger and way less famous than him, and they all just work together. The problems of Crosby’s career seem like they were pretty situational. Much later, he found a way past all that.

7. “ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE”

The last Billboard #1 hit of the ’80s was also the last chart-topper for Phil Collins, a man who spent a solid decade as an unlikely chart sensation. Collins’ well-intentioned lament about poverty also gave David Crosby his first chance to sing on a #1 hit in nearly a quarter century.

Phil Collins wanted to sing with David Crosby because he hoped that “Another Day In Paradise” would evoke the protest music of the ’60s and ’70s. In Collins’ mind, Crosby’s presence worked as a symbol and a reminder, and it tied his song in with a grander tradition. I don’t think Collins succeeded there; “Another Day In Paradise” is an extremely 1989 song. But I like the way those two voices match up. Crosby always knew how to fit his voice to what someone else was doing.

Phil Collins’ respect for David Crosby was real, and Collins repaid the favor many times over. In 1993, Phil Collins co-wrote, produced, and sang on David Crosby’s single “Hero.” That song made it to #44 on the Hot 100 — the highest that Crosby ever went as a solo artist. More importantly, Collins famously paid for Crosby’s 1994 liver transplant, so maybe we have Phil Collins to thank for the last 29 years of David Crosby’s life.

8. PRODUCING SONG TO A SEAGULL

In 1967, Joni Mitchell had written a few songs that were hits for artists like Judy Collins, but she’d never made a record of her own. When she signed with Reprise, part of the deal was that the label assigned her David Crosby as a producer. Crosby has since said that he had no idea what he was doing. He didn’t even know how the microphones should be set up in the room, so Mitchell’s debut album Song To A Seagull has weird tape hiss and reverberating bass sounds throughout.

With 56 years of hindsight, though, I like the way Song To A Seagull sounds. At this point, we’ve had decades of people going intentionally lo-fi, and so the slightly off-kilter intimacy of that Joni Mitchell record casts its own type of spell. It seems to exist out of time in a slightly intoxicating way. Sometimes, you make good shit by accident. Maybe that’s what Mitchell and Crosby did here.

9. THE OCCUPY WALL STREET PERFORMANCE

As a political movement, Occupy Wall Street was beautiful and frustrating and idealistic and unrealistic. Its aesthetics were powerful, and its goals were nebulous. This must’ve all looked pretty familiar to David Crosby. Plenty of famous people stopped by Zuccotti Park in the fall of 2011, and some of them had mysterious intentions. (What, for instance, was Kanye West doing there?) But when David Crosby and Graham Nash came through to lead an acoustic no-microphones singalong, it still made for a moving image.