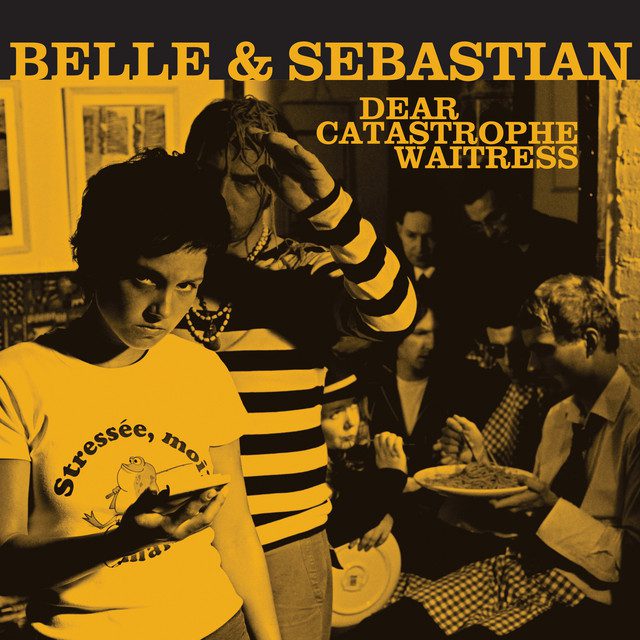

In 2015, I went with a friend of mine to see Belle & Sebastian play Radio City Music Hall in support of their great album Girls In Peacetime Want To Dance. It was a bit surprising that they were playing such a huge venue in the first place, but they’ve slowly developed a multi-generational cult following over the years (I’ve heard some MFA programs won’t confer an English degree unless you can prove you own at least three of their albums) and brand name indie rock icons can generally play disproportionally large venues in New York City. But the real surprise was the show itself, particularly the part involving the group of enthusiastic backing dancers with coordinated moves (all of whom I assume were fans or friends of the band), as well as moments when frontman Stuart Murdoch enthusiastically joined in. Reader, at one point my guy was out there doing high kicks. Just wild stuff. At one point, I turned to my friend and said, “Back in the day, this man was so shy he wouldn’t even get his photo taken.”

People change, as do bands. Murdoch and former bassist Stuart David initially formed Belle & Sebastian as a project for their college’s music business program; their debut Tigermilk was more or less their thesis project, and it was issued, initially with a very limited run, by Stow College’s label. The Glasgow collective was famously reclusive in the ’90s — rarely playing live or giving interviews, not posing for publicly stills or album covers. Murdoch later explained that it was in part because he was still recovering from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

The band’s mystique, a steady stream of winsome singles such as “Lazy Line Painter Jane” and masterpieces such as If You’re Feeling Sinister and The Boy With The Arab Strap earned them one of the most rabid, if polite, fan bases of the late ’90s. But the start of the ’00s was a bit rough on Belle & Sebastian. Their 2000 album Fold Your Hands Child, You Walk Like A Peasant was criticized for being uneven (Alternative Press deemed it the “Belle & Sebacklash”), likely the result of Murdoch ceding the reins of the collective a bit too much, which led to a feeling of treading water and too many songs where his authorial voice was muddy. Then they reportedly had a difficult time working with director Todd Solondz on the score for his film Storytelling and subsequently found themselves caught up in the press’ turn against the misanthropic director. (And while the band didn’t direct the film or anything, the association ended up being a bad look. To call Storytelling “racially problematic” would be a vast understatement.) There were also lineup headaches, as David left in 2000 to focus on his group Looper and his writing career, then singer Isobel Campbell ended her relationship with Murdoch and left the band during a tour. And there’s always the matter that artists that help define an era can sometimes find it hard to move forward when the era ends.

These days, Murdoch gives plenty of interviews. Heck, I’ve talked to the dude. He’s made a film and collaborated with Carey Mulligan. B&S now make videos, play music festivals, tour heavily, and generally act like a conventional, albeit one-of-a-kind, indie band. And the turning point that led to this perhaps in-retrospect surprising career stability was their sixth album Dear Catastrophe Waitress, which turns 20 today.

Belle & Sebastian had signed with the UK mega indie Rough Trade, and Murdoch once told me “they were quite adamant that they wanted us to try and follow a more static commercial route for a while.” The band also became serious about touring, perhaps realizing post-Napster it would be the only way they could make a living as musicians. (Murdoch had kept his job as a caretaker for a church until around the release of Waitress.) And so they inaugurated this new era by recentering the band around Murdoch and hiring Trevor Horn, a British producer and former member of the Buggles whose discography ranges from Pet Shop Boys to Le Ann Rimes. (Shortly before signing on, Horn worked with the infamous early ’00s Russian pop group t.A.T.u.)

Dear Catastrophe Waitress made it very clear that Murdoch knows what you might think about him. Yes, he’s bookish and introverted. Perhaps even a bit twee. (The public’s tolerance for all things twee is generally so low that you have to be great at what you do to get away with it.) And sure, he’ll own all that, but he’s not always quite as shy as you might think. Opener “Step Into My Office, Baby” makes one thing abundantly clear: Belle & Sebastian Fuck.

We’d never heard this band strut with such brassy self-confidence, as Murdoch hits before-unheard vocal flexes (he’s practically purring at one point) while narrating a true Human Resources disaster, as an office drone succumbs to his boss’s advances, seeing it as the only way to get ahead. “I’m pushing for a raise/ I’ve been pushing now for days.” (Subtlety: not always strictly required in the Belle & Sebastian catalog.)

Throughout the album, Horn updates this band’s sound from its ’60s Greenwich folk roots with bits of New Wave sheen and ’70s studio rock perfectionism while still maintaining their timeless nature. Horn had a way with perfect sonic details, such as the slowdown in “Step Into My Office, Baby” around the drawn out “I’ll be in bed by nine” part, immediately followed by a sudden ramping back up; the out-of-nowhere “and let you settle down” group vocal in “I’m a Cuckoo”; or the light dashes of organ and horn that flavor “Wrapped Up In Books” without calling attention to themselves. It kept the album dynamic and proved this band could reach beyond their core audience without losing their core character.

Belle & Sebastian have often been compared to the Smiths, and for most of their career that was mostly a compliment. While Morrissey and Marr were the kings of mopey ballads, they also ruled indie rock dance clubs with an iron fist. Here Belle & Sebastian included a number of songs seemingly designed to make even their most awkward fans get their sweater-clad bodies onto the dance floor, most especially “You Don’t Send Me” and the borderline frothy “I’m A Cuckoo.” (I can never get over the way he sings “I’d rather be in Tokyo/ I’d rather listen to Thin Lizzy-oh.”)

And like Morrissey (I know, I know) Murdoch is often quite a bit funnier than he is given credit for, as seen on “Piazza, New York Catcher.” Now, I’m not one to be all “sportsball” about this sort of thing, as that’s rude and classist. But my lack of familiarity with professional athletics has been chronicled on this very website. I still think it is a bit rude of Murdoch that he thought a Belle & Sebastian fan would know the name of a New York Mets player, even if the song is a light spoof on the fact that Mike Piazza had to give a press conference to deny rumors he was gay (God, the ’00s could be so shitty). It comes off as Murdoch, a straight man that fans often assumed was queer (he’s a gentle man that has written many songs about same-sex desire; you can see why it would happen) giving a nod of commiseration to a fellow trapped in America’s ongoing asinine moral panic.

Ultimately, even beyond the updated production and more traditional approach, I think the legacy of Catastrophe is its where Muroch begins to step into his Wise Benevolent Uncle Mode; with the pristine studio craft, there are times here that the band resembles an inverse of Steely Dan where “Hey Nineteen” is a warning about creepy old dudes.

Murdoch once told me, “To an extent in the songs, I want to console the listeners and take them aside and help. I really feel this sense of purpose that I just want to be the whisper in somebody’s ear that actually takes them away from their suffering.” This album is where this mission really comes to the fore. He knows his band attracts the forlorn and heartbroken, those who think they will never find real love, never find a place in the world and who will always long to live in the more romantic, wistful place he created with his words. (Or so I gather. I wouldn’t know anything about this, mind you.) On “If She Wants Me,” he gives the sort of timeless, heartfelt wisdom every young weirdo needs to hear at some point: “You are too young to put all of your hopes/ In just one envelope,” “You may think you’re alone/ But you may think again,” and “Things fall apart/ I don’t know why we bother at all/ But life is good/ And it’s always worth living/ At least for a while.”

And then there is “If You Find Yourself Caught In Love,” one of Murdoch’s very best songs, a plea to turn away from despair that suddenly morphs into one of indie rock’s best anti-war missives (“Killing people’s not my scene/ I prefer to give the inhabitants a say/ Before you blow their town away.”) Over an orchestra of backing vocals and cascading strings, he pleads with anyone who needs to hear it to stave off despondency and to never give up, preaching that no matter how distraught you are, it is never too late to start again. (I won’t bore you with my life at the time when this album came out, I’ll just note that when I heard them play that song in 2004, I had full body chills and started crying.) “Things will change/ I’m not saying overnight,” he assures, before nudging the listener, “but something has to give.” Words of sage advice from a survivor who knows how true they are.