Ted Leo has a hell of a voice. Upon discovering his music two decades ago, the first thing I noticed about Leo — because how could you not — was the way he whipped around that wild falsetto, deploying it in piercing bursts and explosive roars. He was a kamikaze pilot guided by musicality as much as fervor, fearlessly pushing to the top of his range until his songs exploded. Few frontmen in the punk-rock realm have ever wielded such potent vocal cords, and Leo arguably never sent them careening through a better batch of material than on Hearts Of Oak, the second LP credited to Ted Leo And The Pharmacists, released 20 years ago this Saturday.

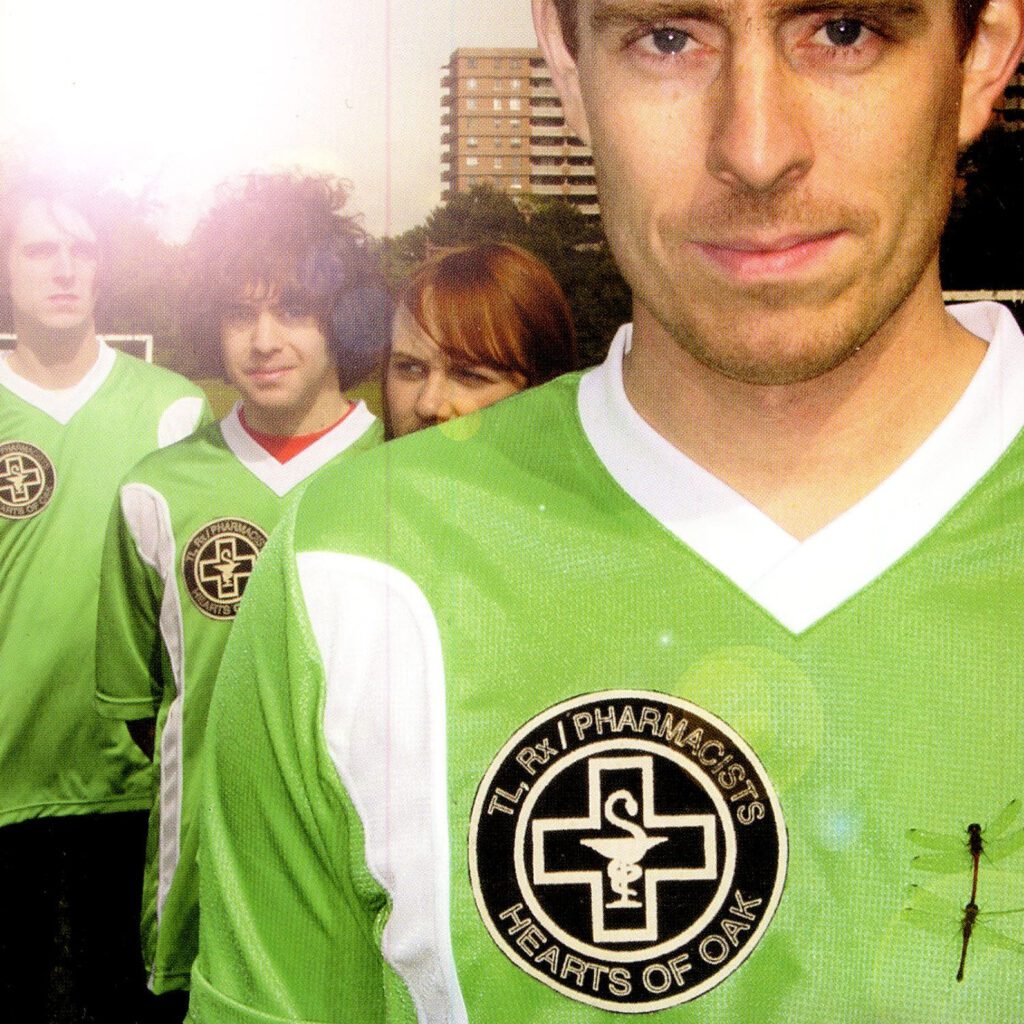

What was just as readily apparent, and just as crucial to the essence of Ted Leo, is what he said with that voice. Having come of age in punk bands, most famously the recently reunited Chisel, Leo brought fierce idealism and fire-eyed intensity to his songs. Drawing inevitable comparisons to the Clash, he made poppy yet adventurous rock music laced with clarity and conviction. On Hearts Of Oak, Leo raged at hypocrites and scoffed at the prospect of “another shitty war to fight for Babylon.” Even the title was a sociopolitical statement, a dual reference to Ghanaian soccer underdogs on the global stage (hence the uniforms on the cover art) and Cockney slang about being flat broke. On an album that plunged Leo into the indie-rock mainstream — one of the first to receive a Best New Music designation at Pitchfork, with concurrent raves from legacy mags Rolling Stone and Spin — that expressly political posture stood out glaringly in the early weeks of 2003.

This was the height of the Meet Me In The Bathroom era, a time when sloshed garage rock, coked-up dance-punk, and proudly gaudy electroclash were among the trendiest subgenres in indie music. (In that Pitchfork review, Rob Mitchum cast Leo as the antithesis of “the insidious ‘Return of Rock!’ movement.”) The parallel walled-off ecosystem known as punk was well into its Warped Tour gentrification, baptized in the toilet humor and teen soap opera sentimentality of blink-182. Hearts Of Oak arrived at the tail end of a post-9/11 moment defined by revelry and escapism, an era when critique of the American empire was rare and most of the discussion of policy in pop culture was on the Toby Keith wavelength. About a month after Leo’s album dropped, the US declared war on Iraq and incited a new wave of popular protest music. But a lot of the political punk and indie rock associated with the George W. Bush era wouldn’t materialize until a year or two after Hearts Of Oak. With rare exceptions like Sleater-Kinney’s One Beat, not many of Leo’s most visible peers were making anything resembling protest music when he was putting this album together.

Leo noticed. On lead single “Where Have All The Rude Boys Gone,” he wondered aloud what has happened to punk’s history of antiracism and progressive politics, piling on references to the Specials amidst lively riffs that drew endless comparisons to Thin Lizzy and Dexys Midnight Runners. “The Ballad Of The Sin Eater” — which could pass for early LCD Soundsystem if James Murphy cared about global politics more than scene politics — grapples with the world’s disdain for America in the aftermath of 9/11, circling back to the refrain, “You didn’t think they could hate you now, did ya?” And although many have heard the sweeping slow-build “The Anointed One” as a George W. Bush diss track, it’s actually about Leo’s former Notre Dame classmate Congressman Mike Ferguson (R-NJ), whose pivot to right-wing politics left Leo feeling betrayed. “My songs often start with a question or a frustration about what the government is doing or how crappy the business world is, and then it usually winds up expressing my personal feelings,” Leo told Socialist Worker in 2004. “I don’t have the acumen to write a political treatise, but maybe the plus side of that is that by expressing my own confusion about the world, it becomes a little more universal and understandable.”

It helped that those emotions were being funneled into tight little pop songs, tracks that could only contain so much anxious energy because they were so brilliantly constructed. Even better, Leo now had a consistent backing band of Pharmacists behind him, lending the album a sonic heft and coherence that was sometimes lacking on 2001’s The Tyranny Of Distance. Over the course of 55 minutes, Hearts Of Oak pulled from riff-slinging barroom rock, power-pop, ska, even Celtic folk on the string-laden closer “The Crane Takes Flight.” Besides the aforementioned Thin Lizzy and Dexys, the common reference points were Elvis Costello and Nick Lowe, masters of smart and punchy pop-rock with a sneer. In Spin, Chris Ryan raved, “The songs are flat-out rollicking, like what Fugazi might come up with if their tour-van radio got stuck on the classic-rock station.”

It’s instructive that, in a CMJ interview, Leo drew a connection between his own music and anarchist one-hit wonders Chumbawamba’s “Tubthumping,” a song “about getting laid off, but sticking together and getting through it.” Leo continued, “There’s nothing wrong with having people dance to music they’ll go home and think about.” The thinking was optional, but with songs like these, the dancing was nearly involuntary. The ultra-hooky “Hearts Of Oak” grooved harder than most of the era’s self-professed disco-punk bands and pilfered Television’s high-string chord riffs at least as well as the Strokes. “Tell Balgeary, Balgury Is Dead” toggled between tight, jittery rhythms and a rocket-fueled chorus slathered in organ chords, as if it had shot 25 years forward from This Year’s Model, picking up a quarter-century of punk-rock history along the way. “I’m A Ghost” and “The High Party” may be two of the bounciest consecutive tracks on any album released this century.

Best of all was “Where Have All The Rude Boys Gone.” There’s a reason the song got its own music video, was performed on Conan (with “NO WAR” written on Leo’s guitar in duct tape), and was slotted close to the start of the album. The song reveals itself as a masterpiece from the very first listen, from its galloping foundational riff to its explosive chorus to its spine-tingling finale. Over a low-key finger-snapping beat, Leo and his bandmates keep piling on vocal layers and instrumental tracks, building intensity little by little until everything breaks open into one last burst of arena-ready bombast. It’s a near-perfect encapsulation of Hearts Of Oak’s appeal: hooks upon hooks, a level of complexity people don’t typically associate with punk, ideas and references flying past you faster than you can even grasp them, nervous tension winding up to a point of spectacular release.

Four months after Hearts Of Oak dropped, a friend and I drove up from Columbus to see the Pharmacists play at a tiny club in Bowling Green, Ohio. Leo was coming off an injury to his vocal cords — apparently there’s a point at which wailing like a wild man can be dangerous to your health — but there were no signs of rust that night. The band barreled through banger after banger, matching the dynamism heard on the album. The crowd responded with flailing limbs and rousing approval. During what should have been a climactic run through “Where Have All The Rude Boys Gone,” the power went out onstage, eliminating most of the sounds from a normally elaborate arrangement. But the band kept playing through the chaos, and Leo kept singing too. We could hear him loud and clear.